Economists are worried about the future of the U.S. economy. That was the takeaway of a Reuters poll last week of more than 100 economists, who forecast a one-in-three chance that America would suffer another a U.S. recession within the next two years. “While predicting turning points in economic cycles is no easy task, the recovery from the devastating 2007-2009 financial crisis has been unusually lengthy,” Reuters reported, “and the latest poll showed some signs the current economic expansion will end soon.”

Reuters understates the matter: Economic predictions are no more reliable than Super Bowl ones. After all, those same economists predicting a recession also forecast an average of 2.8 percent growth in 2018, due to the Republican tax cuts passed late last year. But this much is certain: A recession in the next couple of years would be catastrophic for the many millions of Americans who haven’t recovered one bit since the last one.

The skyrocketing cost of gas, which hit a four-year high over Memorial Day weekend, isn’t helping matters. A political crisis in Venezuela has stalled virtually all oil production there, and oil traders are spooked by President Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal: If the U.S. reimposes sanctions on the country, up to one million barrels per day would vanish from the global supply. Those factors, along with fears that Trump’s new national security team will create more tension in the Middle East, have caused the price of oil to rise by around 50 percent over the past year, peaking at $73 a barrel.

Oil price shocks historically have been a main cause of recessions. Higher fuel and heating costs raise the cost of living, as well as the cost of transporting goods around the country and the world. The U.S. produces much more of its own oil these days, and it has come a long way in energy efficiency. But plenty of the global economy still runs on the burning of crude, and a price spike can still pack a wallop. The subsequent inflation in consumer goods sparked by rising gas prices can prompt the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates, further dampening investment and slowing the economy.

But events in the past couple of days reinforce why you shouldn’t bet on the timing of a recession. Indications from Saudi Arabia and Russia that they would increase their oil supply by one million barrels per day brought prices down by 10 percent. Oil-producing countries have a lot of tools to stave off runaway prices. They want to keep oil in the sweet spot: high enough to make money, low enough to facilitate growth.

Nevertheless, Goldman Sachs remains convinced that the price of oil will continue to rise, with expectations of $82.50 a barrel by this summer. OPEC countries can raise their output to try to control the cost, but may not be able to offset major production snarls or regulatory changes that can send prices escalating. Analyst Bob Parker told CNBC that prices could reach $100 if there were a “complete collapse” in Venezuelan production.

Oil prices aside, other economic indicators suggest a recession in the not-too-distant future, perhaps by the last year of Trump’s current term in 2020. There are obvious political ramifications to that. Trump currently gets relatively high marks on the economy; a slump during a presidential election year would damage hopes of a second term. But it would also damage all the “forgotten men and women” who have been put further and further behind with each cycle of recession and recovery.

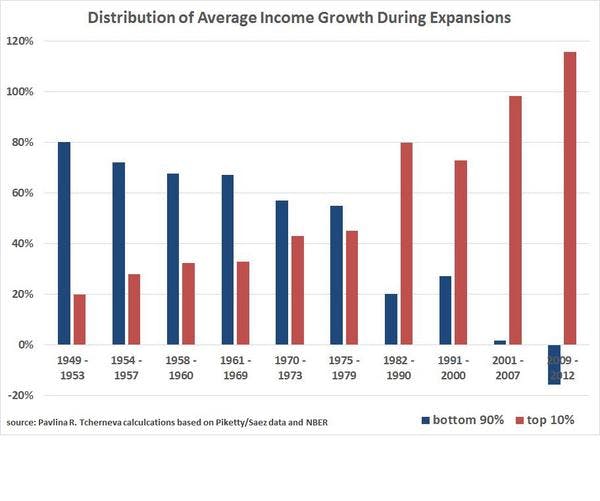

Bard College economist Pavlina Tcherneva constructed the best visual depiction of this phenomenon, with a chart showing the distribution of post-recession gains. In the 1940s and ’50s, the bottom 90 percent of income earners enjoyed at least two-thirds of the benefits. In the 1980s and ’90s, they saw only 20 percent of the gains, and in the recovery after 9/11, that number fell to 2 percent. After the financial crisis of 2007, the bottom 90 percent saw negative gains—that is, they lost ground during the recovery.

Tcherneva’s chart only goes until 2012. But the dynamic appears to have continued in the Trump era. A recent poll found that only 12 percent “feel they have benefited a lot” from the economic upswing, an almost perfect alignment with Tcherneva’s chart. And that’s not likely to change. In a candid conversation at the Dallas Federal Reserve, CEOs stated flatly that workers will not be getting broad-based raises anytime soon. “It’s just not going to happen,” said the CEO of Coke’s Florida division.

If a recession does strike in the next couple of years, how would the Trump administration and Congress respond? Not a single House Republican voted for President Barack Obama’s fiscal stimulus in 2009, and only three Republican senators did. Trump and the GOP Congress have talked already about a second tax cut. Meanwhile, Republicans are busy trying to load up safety net programs with work requirements, which would be especially counter-productive in a recession.

No one knows when the next recession will come, but you don’t need a poll of 100 economists to know that when it does, it will be doubly painful for the majority of Americans who feel like they’re still recovering from the last one.