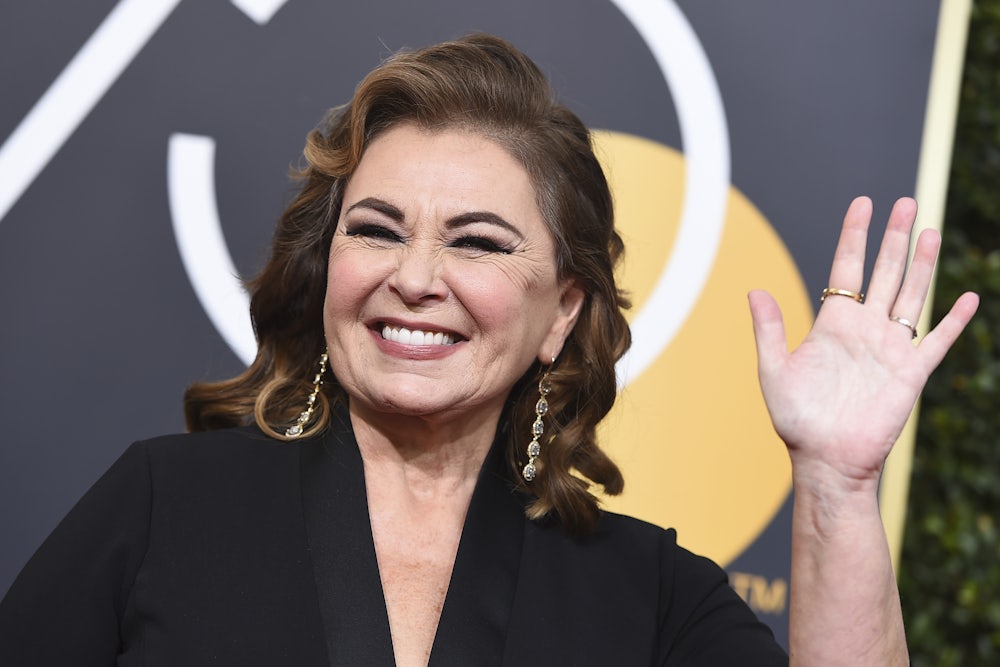

Roseanne Barr went from being the star of television’s most-watched series to being unemployed this week, and blamed her demise partly on a popular sleep drug. The Trump-supporting actress said on Wednesday that she was under the influence of Ambien when she tweeted racist comments about former White House adviser Valerie Jarrett, which caused ABC to cancel Barr’s show. “It was 2 in the morning and I was Ambien tweeting,” she wrote.

Barr took some considerable heat for the excuse. “I am an expert of Ambien abuse,” tweeted Mother Jones senior editor Ben Dreyfuss, who said he went to rehab twice for the drug. “Ambien doesn’t make you say racist shit.” Even drugmaker Sanofi, which manufactures Ambien, weighed in. “Racism is not a known side effect of any Sanofi medication,” the company tweeted.

Barr eventually said she only had herself to blame for comparing Jarrett—a black woman—to the “Muslim Brotherhood” and Planet of the Apes. Ambien was “just an explanation,” she wrote, “not an excuse.” At that point, though, it was too late. “Ambien made me racist” had already entered meme territory.

(Chanting)

— Jason O. Gilbert (@gilbertjasono) May 30, 2018

WE! JUST! TOOK! AMBIEN! pic.twitter.com/esu3IMj8gu

If your racism lasts longer than 4 hours...call your doctor? https://t.co/TTW8ilGjXv

— John Berman (@JohnBerman) May 30, 2018

If Barr really did take Ambien before tweeting that night, could it have impacted her decision to tweet something racist? Given Barr’s Twitter history, it seems unlikely she needed medication. But it’s not out of the realm of possibility for Ambien to make someone say terrible things, according to Michel Cramer Bornemann, a longtime sleep medicine researcher and the lead investigator at Sleep Forensics Associates.

“Racism specifically is not a side effect of Ambien,” he said. “But unrestrained behavior from an individual that lacks impulse control—things like sleep tweeting, sleep texting—are all possible side effects.”

That’s because of the way Ambien, a sedative, forces the brain into sleep. During natural sleep, some parts of the brain stay on while other parts turn off—including the prefrontal cortex, which “helps us know what’s good and bad, to have executive goal-driven behaviors, to have a plan that’s pre-thought out, and provide balance and appropriate context to social interaction,” Bornemann said.

Ambien induces sleep in part by turning off the brain’s prefrontal cortex, at which point the brain is “not able to provide inhibitory control,” Bornemann said. Meanwhile, other parts of the brain are still online—most notably the limbic system, which controls basic emotions, like fear and anger, and animalistic drives, like hunger and sex. If you’re not actually asleep at this point when you’re on Ambien, Bornemann said, “You’re acting in a primal way.” That’s when you can get in real trouble.

Bornemann, who consults plaintiffs and defendants in criminal cases related to sleep disorders, said about a third of the 350 cases he’s seen involved the side effects of Ambien. Most cases are DUIs—people who got in the car while on Ambien, not knowing what they were doing. “When they start to have memory, they’re typically in a holding cell,” he said. Others are cases of sexual assault, where the perpetrator claims no memory of committing a heinous act.

Of course, Bornemann regularly deals with the possibility that criminal suspects are lying about being on Ambien to get out of a crime—just as it’s possible that Barr might not be telling the truth about what caused her racist tweets. But “Ambien tweeting” is a real phenomenon, or at least something Twitter users often accuse each other of doing.

ambien tweeting is a dangerous game

— Sam Altman (@sama) June 7, 2017

Dreyfuss told me he sent “many incoherent tweets” during an Ambien relapse two years ago. “You definitely send things that you think are funny that are not or will be perceived in a way you anticipate but are not,” he said. Still, he’s skeptical the drug could cause someone to suddenly become racist. “It just makes you looser with things you already believe,” he said.