The date is December 21, 1974, and Sy Hersh is working late on one of his many exposés of the CIA’s domestic spying program for The New York Times. He’s 5,000 words deep by midnight, well over his allotment in the next day’s paper. The night editor won’t budge, and in response, as Hersh recalls in his new memoir Reporter, he goes “nuts.” He calls the paper’s editor Abe Rosenthal, at home, at two in the morning. His wife Ann picks up but explains “with much bitterness” that Abe has left her and is at his girlfriend’s house. Ashamed, Hersh hangs up. But after a few minutes he calls her again. Does she know the girlfriend’s name?

Seymour Hersh is not so much a journalist as a terrier, except the prey he’s hardwired to sniff out is Henry Kissinger. The story of calling Rosenthal’s wife illustrates his total disregard for other people’s mortification; his self-advocacy to the point of conceit; and his total prioritization of the story over all else, to the extent that he will hunt down his editor’s mistress to get that editor to add a page to the Sunday Times for him and him alone. And to the betterment of the American people, of course.

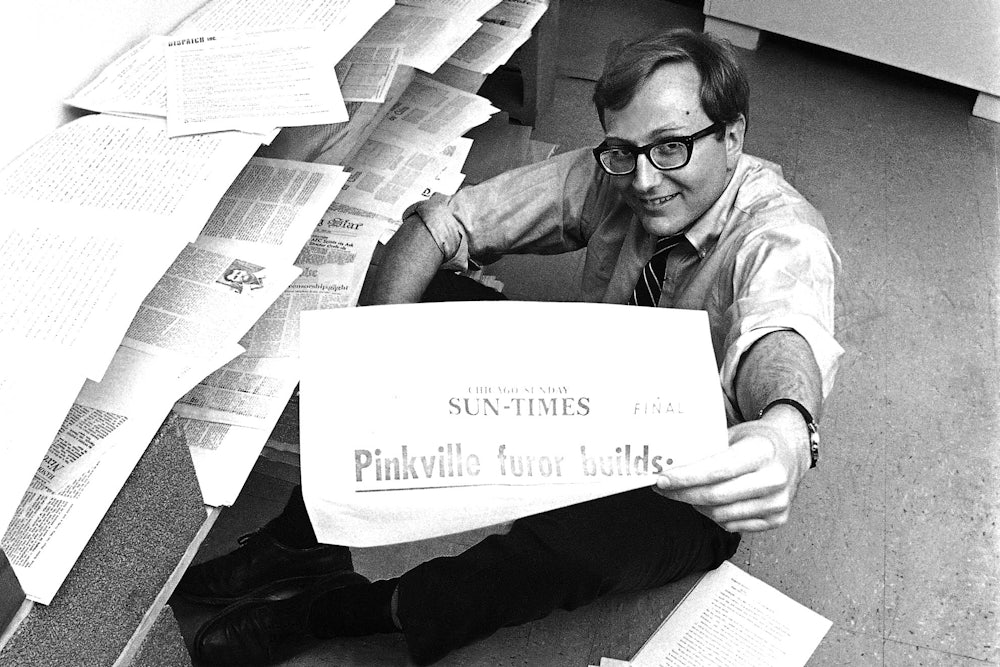

Hersh’s reporting career has been defined both by his zeal and by the United States’s warmongering exploits in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1969, Hersh independently reported the unspeakable abuse and murder of people in Vietnam at My Lai by the American armed forces, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize at age 33. He covered Watergate. He made Kissinger—architect of paranoia—paranoid. In the ’80s he covered Korean Flight 007, in the ’90s Israel’s nuclear arms development.

War, again, brought him to the forefront of investigative journalism in recent decades. Hersh worked for The New Yorker during the Iraq War (“There was a point with The New Yorker where I thought they should rename the fucking magazine the Seymour Hersh Weekly,” he told Slate in 2015), moving his rifle sights from Kissinger to Dick Cheney. It was Hersh who detailed the abuses at Abu Ghraib in 2004, and it was Hersh again who wrote the 10,000-word revision of the story of Osama Bin Laden’s killing for the London Review of Books in 2015.

Hersh is not just an example but the template of a dogged reporter who will hold a violent and hubristic government to account for its crimes. Throughout his career he has been accused of conspiratorial thinking, subjected to anti-semitic insults (from Eugene McCarthy’s wife, for example), and suspected of communist sympathies. For younger journalists Hersh seems to come from another world. As his memoir details, he was proud and disdainful to editors and had his “paranoia” continually vindicated in a way that actually improved the government’s conduct, if marginally. In our era of the data-state and data-media, with all our mysteries guarded by private companies that seem to feel no duty to the public that they profit from, few of the hallmarks of Hersh’s career exist any longer.

As a 2015 n+1 editorial put it, Hersh “harks back to an era of heroically paranoid journalism—the kind that once brought down governments.” It is an era that journalists today “no longer feel themselves to be living in.” One important change has been the complicity of the big newspapers with the government’s agenda, especially through the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Washington Post ran the Watergate story, the Times published the Pentagon Papers, but at the turn of the millennium, “one dubious story after another was simply rubber-stamped by the media, not least the lies on which the government founded its case for the invasion of Iraq,” n+1 writes. “These lies were presented as fact by the Times and ecstatically supported by the paper’s editorial board.”

The experience of reading Hersh’s memoir is like visiting a lost world. His book contains stories of reporting that are fractally detailed. Here is how Sy Hersh heard about the soldier on whom they wanted to pin the blame for My Lai. Here is how Sy Hersh tracked down Lt. Calley, who was later convicted of killing 22 people in that massacre. Here is how Sy Hersh got the file. Here is how Sy Hersh sold the story.

The book is organized chronologically, beginning briefly with his childhood in the South Side of Chicago, working in his parents’ dry cleaning shop, then rampaging through to the present with little or no mention of his personal life. It’s all reporting—dense and detailed reporting on reporting. That iterative and pointillist style of telling a story does fall into a genre: noir. As a kid working at Chicago’s City News, he recalls “wise guys full of badinage.” When he’s trying to track down Calley, he finds a disillusioned army kid to help him out. “We synchronized our watches,” Hersh writes. They would meet behind the barracks “in precisely seven minutes.”

To put it in a callow way, this stuff is cool. It’s also very masculine. Almost every person in Hersh’s memoir is a man—a sign of the time and the industry. But there’s an interesting moment that Hersh did not have to include. In 1974, he writes, Hersh heard that Nixon’s wife Pat was in hospital after being punched by her husband. It was not an isolated occasion. He did not report on the story, he told Nieman Foundation fellows in 1998, because it represented “a merging of private life and public life.” Nixon didn’t make policy decisions because of his bad marriage, went the argument. Hersh was “taken aback” by the response from women fellows, who pointed out that he had heard of a crime and not reported it. “All I could say,” Hersh writes, “is that at the time I did not—in my ignorance—view the incident as a crime.”

It is to Hersh’s credit that he records many of his own mistakes in his memoir, and this is one subject on which his thinking has fully changed. “I should have reported what I knew at the time or, if my doing so would have compromised a source, have made sure that someone else did.” But if Hersh is “a survivor from the golden age of journalism,” as he opens this book observing, then his oversight in categorizing domestic violence as crime must be recorded as a failing of that age.

Dwight Garner of The New York Times faults Reporter for lacking detail and color about human beings who are not Sy Hersh. It’s true: This is not a psychological or social portrait of any of the major players who ran newspapers during the decades covered in the book. And the Nixon anecdote reveals that what is left out of Reporter, namely women and a political consciousness that includes women, speaks a little loudly for comfort. Hersh is not a political theorist, nor a literary memoirist, nor a paragon of journalistic behavior. He’s a reporter. Looking back over his career from today’s vantage point, he is something of an incomplete hero. It’s easy to mourn the loss of this industry’s old form, and to lionize Hersh as its most ferocious remnant. The past is a foreign country, and, for better or worse, they did journalism differently there.