In April, President Donald Trump signed a declaration to create the first-ever National Foster Care Month. The month of May, it said, would celebrate those who provide temporary homes to children without parents or guardians. But May would also recognize a darker reality—“the plight of innocent children who are in foster care because their lives have been disrupted by neglect or abuse.”

Today, the American foster care system is bracing for an influx of children whose lives have been disrupted by the Trump administration itself. According to a Monday report from the Washington Examiner, approximately 250 migrant children are being taken from their parents or guardians per day as a result of Trump’s new family separation policy. If that trend continues, as officials expect it to, around 30,000 children would be in the government’s custody by August. That figure doesn’t include the thousands of minors who show up at the border without a guardian every month, a number that has increased significantly in 2018.

The Trump administration insists these kids will be alright. “The children will be taken care of—put into foster care or whatever,” White House chief of staff John Kelly told NPR in May. That’s exactly what’s happening. “As the Trump administration takes more migrant children into custody at the Mexico border,” The Washington Post reported last month, “new statistics show the government is placing a growing number in long-term foster care, sometimes hundreds of miles from their jailed parents.”

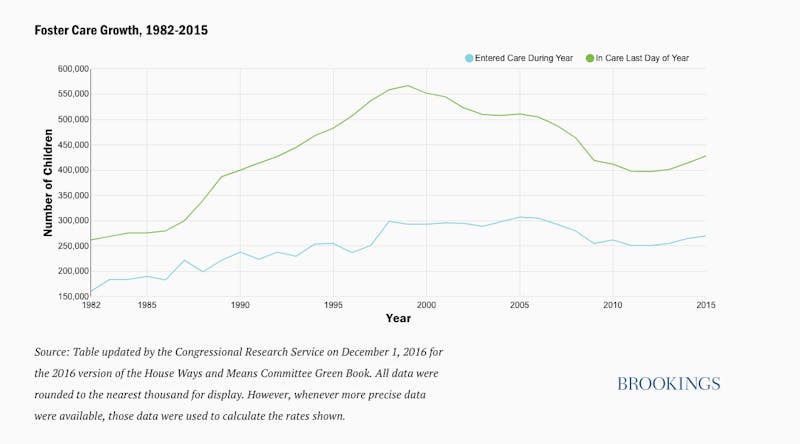

But the foster care system is already struggling to provide stable living situations for the 500,000 children who need assistance. The number of kids entering the system has increased every year for the last four years, but there hasn’t been a concomitant increase in social workers to help them and group homes or families willing to take them in. “American foster care,” the Post reported last year, “is in crisis.”

Trump responded to this growing problem in February by signing into law a massive overhaul of the system that redirects funding and resources for foster care services toward programs that keep children with their parents. But what about children whose parents have been jailed or deported by immigration officials? Can a strained system designed for abused and neglected American kids handle an influx of child migrants who are struggling with their own unique problems?

Unlike their parents, children apprehended at the border can only be legally held in immigration detention facilities for three days. After that, they must placed in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement. While ORR employees search for permanent placements, they put the kids in temporary shelters run by outside contractors.

Children forcibly separated from their parents are legally considered Unaccompanied Alien Children, a designation normally reserved for kids who show up at the border by themselves. According to HHS data, these children spend an average of 51 days in temporary shelters. Eighty-five percent eventually ended up in “sponsor homes” with U.S.-based relatives. About 10 percent wind up in foster care.

The White House insists the statistics will be different for the separated children; that they’ll returned to their parents within five to ten days. But that’s not how things are playing out in reality, said Sandy Santana, the executive director of Children’s Rights, one of the organizations suing the Trump administration over its separation policy. “We’ve heard stories of parents being deported and their children being left behind,” he said. “And then kids are being sent all over the country, and that distance makes it less likely that these reunifications are going to take place quickly. So our fear is that many of these children will linger in foster care.”

That may be happening already. A Seattle foster care facility, for example, recently accepted six children who were separated from their families at the border. And Michigan foster care agency Bethany Christian Services has helped place 58 separated migrant children since May 1, a representative said. That’s a major increase from January, when BCS only placed one separated migrant child. Today, children impacted by Trump’s policy make up 75 percent of the agency’s caseload.

Other organizations say they haven’t served any affected children. “We really haven’t been impacted,” said a spokesperson for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. But that’s because that group only provides resources for more permanent, long-term foster care. “We don’t really have any short-term, transitional sites,” he said.

But some separated migrant children will eventually end up in long-term foster care, former head of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement John Sandweg said in a Tuesday interview with NBC News. “Permanent separation. It happens,” he said, adding that Trump’s policy “could be creating thousands of immigrant orphans in the U.S.” He added that long-term separations normally happen because parents are deported before their children are processed separately.

“Foster care is not a good option for anyone,” Santana told me, citing woeful outcomes for kids that go through it. But it’s an especially bad option for migrant kids, he said, because they’re entering a place for abused and neglected children even though they themselves haven’t been abused or neglected. “You’re imposing trauma on them unnecessarily,” Santana said.

Foster care is supposed to be a last resort for children who face danger in their own homes—the number of whom is rising. After hitting a 25-year low in 2012, the number of kids in foster care increased by 10 percent nationwide from 2012 to 2016; in six states, it has increased by more than 50 percent. That’s largely due to the opioid epidemic, Santana said. “We’re now seeing systems with very high case loads, a lack of foster homes to place kids, and a reliance of group homes, which are not the best settings for kids,” he said. “We are especially worried that these influx of kids from the border are going to further tax the system.”

If 10 percent of the 30,000 kids expected to be under HHS care by August end up in the foster system, that’s another 3,000 children—admittedly a blip in a system that already serves nearly 500,000 kids. But Santana worries that the figure could be higher, because many potential sponsors now fear deportation if they come forward to take in a child. The relatives of migrant children are often undocumented themselves, or live with undocumented people. “There have been cases where the Trump administration has gone after sponsors who choose to take care of kids,” Santana said.

But the number of new kids entering the foster care system is not what worries Santana; it’s the amount of resources and effort it will take to heal their unique wounds. “These are going to be kids who need deep trauma services because of the trauma of being separated from their parents,” he said. “Even more challenging for the system is that close to all of these kids don’t speak English, and finding Spanish-speaking resources is very difficult.”

The bill Trump signed in February intends to ease the growing burden on the foster care system by preventing kids from entering it in the first place. As USA Today reported, the new law “puts more money toward at-home parenting classes, mental health counseling and substance abuse treatment—and puts limits on placing children in institutional settings such as group homes.” Santana’s organization supports the bill, because he says ultimately it will reduce the number of kids in foster care and free up space for kids who really need it. But he noted that migrant children separated from their parents won’t likely see the benefits of this new law since most of its provisions don’t take effect until October of 2019 or later.

In April, Trump hailed the law as a way to create “more desirable family atmospheres,” based on the well-founded belief that children always fare best when they’re able to remain with their parents. But since then, he’s made clear that his belief in keeping families intact doesn’t extend to those who are in the most desperate circumstances of all.