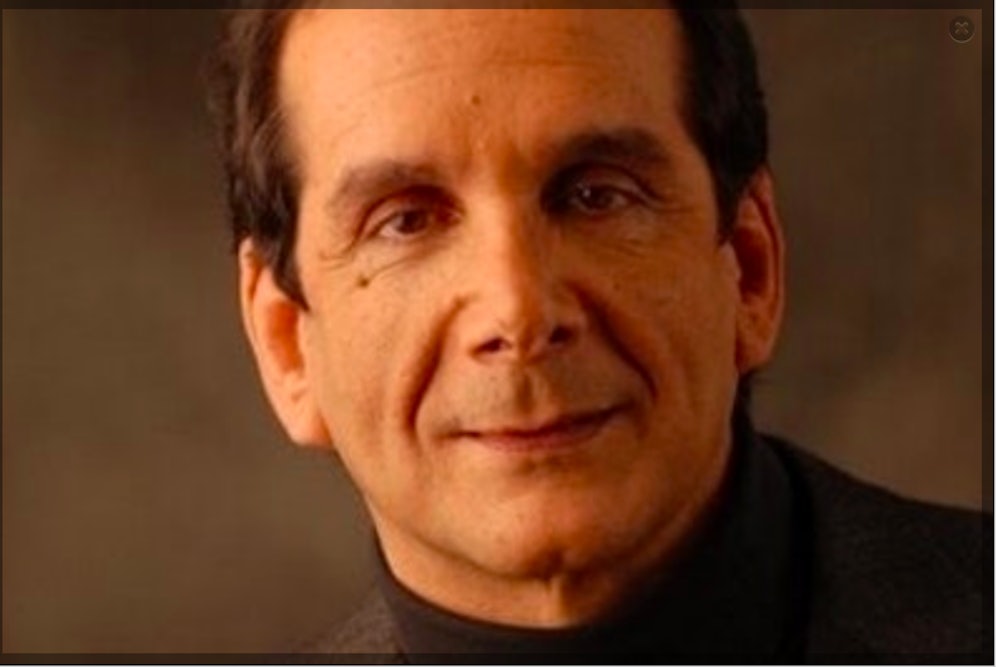

When Krauthammer wrote his first article for The New Republic in 1979, he was a Jimmy Carter–supporting liberal. When he wrote his last piece in 2003, he was one of America’s most prominent conservative columnists, the most forceful advocate for George W. Bush’s war in Iraq and the larger strategy of democracy promotion in the Middle East. Over that time, Krauthammer went through a dramatic political change—one that was characteristic of his generation, but which also marked an important chapter in the history of this magazine and of American liberalism.

Krauthammer became an editor at TNR in 1981, at the start of a decade where the magazine was often at war with itself. The ’80s weren’t just the era of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, but of the reinvention of liberalism under the pressures of a now-dominant right. TNR, under the alternating tenure of Michael Kinsley and Hendrik Hertzberg, was a forum where competing strands of the liberalism battled for dominance. One faction of the magazine, led by Hertzberg, was robustly social democratic and distrustful of military adventurism. The rival faction, whose most eloquent voice was Krauthammer, was moving away from Cold War liberalism and toward a nascent neoconservatism.

Foreign policy was Krauthammer’s dominant passion, and the struggle against Soviet Communism drew him away from his youthful liberalism. Although he worked as a speechwriter for Walter Mondale in 1980, he came to distrust the Democrats as too dovish. After the Cold War, he continued to believe that American global hegemony was crucial for creating a better world. His 1991 essay “The Lonely Superpower” is critical for understanding the worldview of the American foreign policy elite in the years to come. With the clarity and force that graced all his writing, Krauthammer laid out a case for American foreign policy activism during a “unipolar moment”:

I would much have preferred that after the long twilight struggle America enjoy the respite from toil and danger to which it is richly entitled. Alas, there is no end to toil, and it is not just naive but dangerous to pretend otherwise. Even after the defeat of the Soviet threat, we face a highly dangerous new world from which there is no escape. Our best hope for safety in such times, as in difficult times past, is in American strength and will: the strength to recognize the unipolar world and the will to lead it.

Given his belief in America’s responsibility to dominate the globe, it was not surprising that he would be one of the most influential advocates for the post-9/11 attempt to remake the Middle East. He staked his considerable credibility on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq having weapons of mass destruction.

Since the rise of Donald Trump in 2016, much of the Republican Party has rejected Krauthammer’s brand of neoconservate internationalism. Where he wanted America to take up the burden of global leadership, Trump has argued for unilateral nationalism. This provoked the final political shift in Krauthammer’s life, when he refused to vote for the Republican nominee.*

There’s much in Krauthammer’s work to argue with, but no denying the ample testimonies of his personal kindness nor his bravery in rebuilding his life after a swimming-pool accident left him paralyzed him below the waist when he was 22 years old.

But what I do remember is the email Charles Krauthammer sent my dad. I'd like to share it here. pic.twitter.com/FO6hMJvjwz

— Nash Jenkins (@pnashjenkins) June 21, 2018

He was equally brave in facing death. Rest in peace, Charles Krauthammer.

*This article originally misstated that Krauthammer voted for Clinton in 2016. He declared he would vote for a write-in candidate.