Donald Trump’s plan to lower prescription drug prices, announced May 11 in the Rose Garden, is a wonky departure for the president. In his approach to other signature campaign pledges, Trump has selected blunt-force tools: concrete walls, trade wars, ICE raids. His turn to pharmaceuticals finds him wading into the outer weeds of the 340B Discount program. These reforms crack the door on an overdue debate, but they are so incremental that nobody could confuse them with the populist assault on the industry promised by Trump the candidate, who once said big pharma was “getting away with murder.”

With his May 11 plan, Trump is, in effect, leaving the current pharmaceutical system in place. Increasingly, its most powerful shareholders are the activist managers of the hedge funds and private equity groups that own major stakes in America’s drug companies. They hire doctors to scour the federal research landscape for promising inventions, invest in the companies that own the monopoly licenses to those inventions, squeeze every drop of profit out of them, and repeat. If they get a little carried away and a “price gouging” scandal erupts amid howls of public pain and outrage, they put a CEO on Capitol Hill to endure a day of public villainy and explain that high drug prices are the sometimes-unfortunate cost of innovation. As Martin Shkreli told critics in 2015 of his decision to raise the price of a lifesaving drug by 5,000 percent, “this is a capitalist society, a capitalist system and capitalist rules.” That narrative, that America’s drug economy represents a complicated but beneficent market system at work, is so ingrained it is usually stated as fact, even in the media. As a Vox reporter noted in a piece covering the May announcement of Trump’s plan, “Medicine is a business. That’s capitalism. And we have seen remarkable advances in science under the system we have.”

This is a convenient story for the pharmaceutical giants, who can claim that any assault on their profit margins is an assault on the free market system itself, the source, in their minds, of all innovation. But this story is largely false. It owes much to the rise of neoliberal ideas in the 1970s and to decades of concerted industry propaganda in the years since.

In truth, the pharmaceutical industry in the United States is largely socialized, especially upstream in the drug development process, when basic research cuts the first pathways to medical breakthroughs. Of the 210 medicines approved for market by the FDA between 2010 and 2016, every one originated in research conducted in government laboratories or in university labs funded in large part by the National Institutes of Health. Since 1938, the government has spent more than $1 trillion on biomedical research, and at least since the 1980s, a growing proportion of the primary beneficiaries have been industry executives and major shareholders. Between 2006 and 2015, these two groups received 99 percent of the profits, totaling more than $500 billion, generated by 18 of the largest drug companies. This is not a “business” functioning in some imaginary free market. It’s a system built by and for Wall Street, resting on a foundation of $33 billion in annual taxpayer-funded research.

Generations of lawmakers from both parties bear responsibility for allowing the drug economy to become a racket controlled by hedge funds and the Martin Shkrelis of the smaller firms. The current crisis in drug prices and access—as well as a quieter but no less serious crisis in drug innovation—is the result of decades of regulatory dereliction and corporate capture. History shows there is nothing inevitable or natural about these crises. Just as the current disaster was made in Washington, it can be unmade in Washington, and rather quickly, simply by enforcing the existing U.S. Code on patents, government science, and the public interest.

In 1846, a Boston dentist named William Morton discovered that sulfuric ether could safely suppress consciousness during surgery. The breakthrough revolutionized medicine, but when Morton filed a patent claim on the first general anesthesia, one doctor huffed to a Boston medical journal, “Why must I now purchase the right to use [ether] as a patent medicine? It would seem to me like patent sun-light.”

The response reflected a longstanding belief that individuals shouldn’t be able to claim monopolies on medical science. Breakthrough discoveries, unlike the technologies inventors would design to apply those discoveries, should remain open and free to a global community of doctors and researchers, with the backing of the government if necessary.

These norms persisted into the postwar era. In 1947, U.S. Attorney General Samuel Biddle argued that the government should maintain a default policy of “public control” over patents. This, he said, would not only advance science, public health, and marketplace competition, it would also avoid “undue concentration of economic power in the hands of a few large corporations.” When asked on national television in 1955 why he didn’t patent the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk famously borrowed the quip leveled a century earlier against the Boston dentist who invented ether. “Could you patent the sun?” he asked.

By then, though, the economics of medicine had begun to shift, and with them the medical ethics surrounding patents. The public university at that time had become a giant laboratory where government and industry scientists worked together designing missiles, inventing medicines, and engaging in basic-science futzing under the “Science of the Endless Frontier”—a concept promoted by New Deal science-guru Vannevar Bush, who believed that the government should fund the open-ended pursuits of the most gifted scientists. Out of this new world arose new interests and new questions: What happens to the inventions spinning out of government-funded labs? Who owns them, who can license them, and for how long?

Toward the end of the 1960s, new mechanisms hatched out of the National Institutes of Health would transform the industry and drastically expand the opportunities for private profit at the expense of the public interest, ushering in a post-Biddle age of virtually unrestricted industry access to taxpayer-funded science.

In 1968, the NIH’s general counsel, Norman Latker, spearheaded the revival and expansion of a program that had, in the years before the government spent much on science, permitted nonprofit organizations—universities, mainly—to claim monopolies on the licenses of medicines developed with funding from NIH. Called the Institutional Patent Agreement program, it effectively circumvented rules that had been in place since the 1940s, not only making monopolies possible, but also greatly expanding their terms and limits, giving birth to a generation of brokers whom universities relied on to negotiate newly lucrative exclusive licensing and royalty deals with pharmaceutical companies.

In an industry where active ingredients are often bulk-purchased for pennies and sold in milligrams for dollars, the patent is more than just the product. It is a license to print money. An awful lot of money.

Before 1968, inventors had been required to assign any inventions made with NIH funding back over to the federal government. Now, those inventions were being sold to the highest bidder. “Nineteen-sixty-eight was the year the NIH threw its support behind a drug development market based on patent monopolies,” says Gerald Barnett, an expert on public-private research who has held senior licensing positions at the University of Washington and University of California. “It’s kept it there ever since.”

Watching these developments closely was the group of nominally libertarian economists, business professors, and legal scholars at the University of Chicago, known collectively as “The Chicago School.” The industry’s regulatory travails and the new opportunities to commercialize science that had emerged in the late 1960s were of particular interest to the economist George Stigler, a founding member of the Chicago School and its most celebrated theorist after Milton Friedman. Stigler is remembered today as the father of “capture theory,” which holds that because industries have a bigger stake in policy than individual citizens, they will exert greater control over shaping that policy. Industry, he argued, will seek to use their power to hamper competition and shore up their position in the market. Regulation never benefits the public, he believed; instead, it benefits the very industry being regulated. There is a lot of merit in this theory. But instead of arguing for more democratic control over regulation, Stigler argued for its elimination.

Though members of the Chicago School opposed monopolies, Stigler and his colleagues hated the government, not to mention the burgeoning “consumer-rights” pro-regulation movement of the 1970s, even more. If forced to choose between private and public power, there was no contest. Stigler developed his openly un-democratic ideas as chair of the Business School’s Governmental Control Project, whose name reflected a double meaning at the core of the project it served: Advancing the “free market” against government control of the economy can be achieved not only by rolling back the state and eliminating its agencies (the approach Milton Friedman favored—and promoted in the Newsweek column he wrote between 1966 and 1984), but by the invasion and colonization of politics on multiple fronts, especially patent law, regulation, and antitrust and competition policy.

“Pharma was the perfect test case for a neoliberal project that celebrates markets, but is fine with large concentrations of power and monopoly,” says Edward Nik-Khah, a historian of economics who studies the pharmaceutical industry at Roanoke College. “Stigler and those influenced by his work had very sophisticated ideas about how to audit and slowly take over the agencies by getting them to internalize [their] positions and critiques. You target public conceptions of medical science. You target the agencies’ understanding of what they’re supposed to do. You target the very thing inputted into the regulatory bodies—you commercialize science.”

In 1972, Stigler organized a two-day event, “The Conference on the Regulation of the Introduction of New Pharmaceuticals.” Major drug makers like Pfizer and Upjohn pledged funds and sent delegates to the conference—a first and fateful point of contact between Pharma and the organized movement to undo the New Deal and radically remake the U.S. economy to serve an ideology of unfettered corporate power.

Born of this meeting was the echo chamber of ideas, studies, and surveys that the pharmaceutical industry has used to buffer an increasingly indefensible system against regular episodes of public outrage and political challenge. Organized and initially staffed by alumni of the Chicago conference, its hubs are the American Enterprise Institute’s Center for Health Policy Research, founded 1974, and the Center for the Study of Drug Development, founded in 1976 at the University of Rochester and later moved to Tufts. Their research has succeeded in producing and policing the boundaries of the drug pricing debate, most successfully propagating the myth that high drug prices are simply the “price of progress”—carrots that drug manufacturers need to entice them to sink hundreds of millions into research and development, because drugs cannot be developed or tested any other way. In the early 2000s, these think tanks gave us the deceptive meme of the “$800 Million Pill,” a dubious claim about the “real” cost of developing a single drug, which has provided cover for, among other things, George W. Bush to sign away the government’s right to negotiate drug prices in 2004. (The same think tanks now talk about the “$2.6 Billion Pill.”)

“The point of pharma’s echo chamber was never to get the public to support monopolistic pricing,” says Nik-Khah. “As with global warming denialism, which involves many of the same institutions, the goal is to forestall regulation, in this case by sowing confusion and casting doubt about the relationship among prices, profits, innovation and patents.”

While Stigler was marshaling researchers in the think tank world, the market was evolving to include more opportunities for speculative investments and bigger IPOs. Venture capital firms in the 1970s began investing heavily in biotech; soon, young biotech firms, established drug makers and Wall Street were pushing for changes in licensing and patent law to make these investments more profitable. They were aided in this by Edward Kitch, a law professor, Chicago School protégé of Richard Posner, and veteran of the ’72 conference, who worked with AEI’s Center for Health Policy Research. In 1977, he published “The Nature and Function of the Patent System” in The Journal of Law and Economics. It enumerated the many advantages of patents and IP rights, not least their role as bulwarks against the “wasteful duplication” of competition. Patents create the conditions for increased profits that, in turn, increase private sector R&D and spur innovation. (If this sounds familiar, it’s because the paper helped press the record for what has since become the industry’s favorite tune, “Price of Progress,” sung over the years in a thousand variations, including the strained aria of Michael Novak’s Pfizer-funded essay on the moral and Godly bases of monopoly patents, The Fire of Invention, The Fuel of Interest.)

These efforts contributed to a revolution in biomedical IP law during the Carter and Reagan years. The cornerstone of the new order was the University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act of 1980, better known as Bayh-Dole. Drafted in 1978 by the NIH’s counsel Norman Latker (previously seen drafting the IPA regime in 1968), the Act gave NIH contractors new powers over the ownership and licensing of government science, including a right to issue 17-year life-of-patent monopolies—a change former FDA Commissioner Donald Kennedy has compared to the Enclosure and Homestead Acts that privatized the English countryside and the American West. (Latker, for his part, would continue to defend the bill he’d helped craft years later. In 2004, now retired, he told Congress that any attempt to reassert government controls on drug prices would be “intolerable.”)

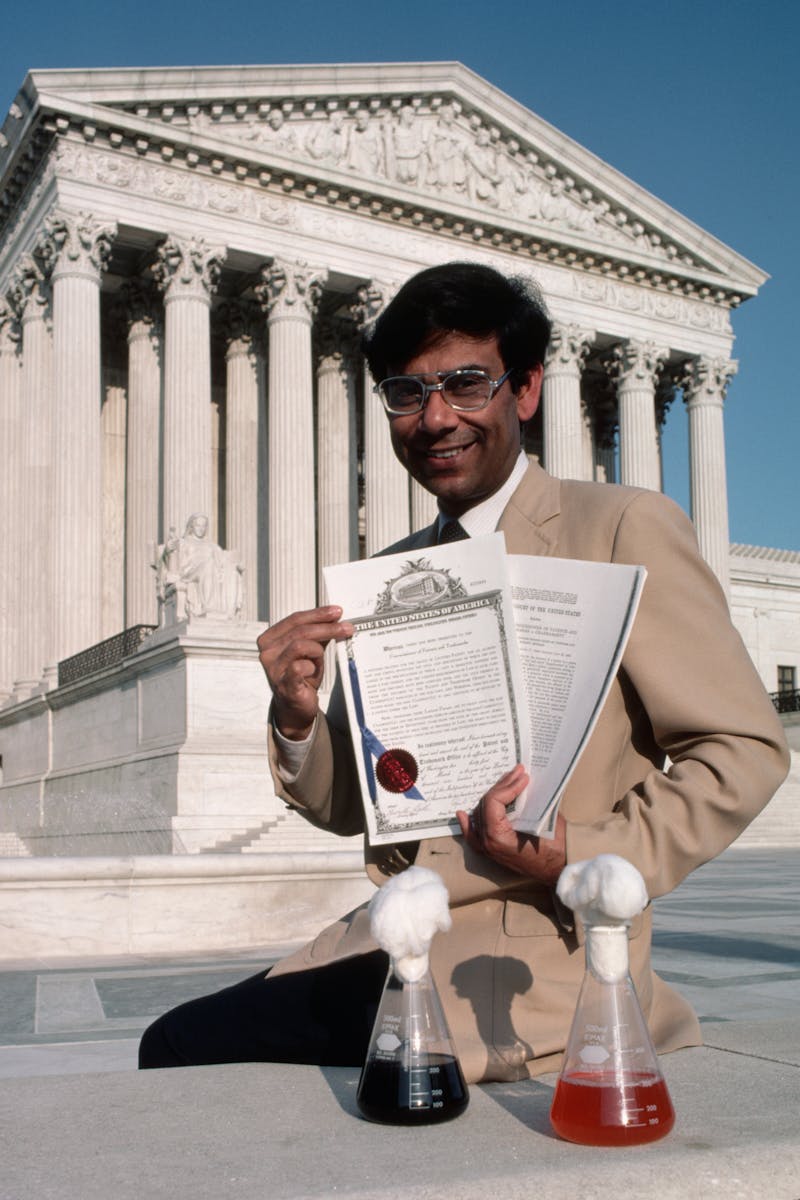

Shortly after the passage of Bayh-Dole, the Supreme Court in 1980 decided a GE scientist named Ananda Chakrabarty could patent genes and genetically engineered organisms, fueling a gold rush in biotech and further sweetening pharma as a destination for investors. “The Chakrabarty decision provided the protection Wall Street was waiting for, encouraging academic entrepreneurs and venture capitalists to explore commercial opportunities in biotech,” says Oner Tulum, who studies the drug sector at the Center for Industrial Competitiveness. “It was the game changer that paved the way for the commercialization of science.”

Presidents from Reagan through Clinton continued to push legislation friendly to pharmaceutical manufacturers. The 1983 Orphan Drug Act provided extended licenses and tax waivers on drugs targeting rare and genetic diseases. A 1986 tech transfer bill established “Cooperative Research Centers” that gave industry a direct presence in federal labs, and established offices to assist in transferring the fruit of these labs to their new commercial partners. Under Clinton, who would consistently expand private access to government research, the FDA Act of 1997 opened the era of direct television drug marketing.

By the early 1990s, a new monster had emerged: an emboldened, triumphant, and fully financialized Pharma. It would help defeat Bill Clinton’s health reforms and go on to reshape the industry, not as something geared toward public needs, the high-risk development of breakthrough drugs, or even long-term profitability, but as a business focused narrowly on predatory value extraction: scooping up government-funded science, gaming the system to extend licenses and delay generic competition, and aggressively seeking short-term stock boosts through maximum pricing, mergers, acquisitions and takeovers.

To understand financialized pharma, just look at what it does with its money. Drug companies have spent the vast majority of their profits in recent years on share buybacks that maximize immediate share value. Donald Trump’s 2017 tax bill, for example, allowed drug makers to repatriate more than $175 billion banked offshore at giveaway rates. Most of this money, including $10 billion by Pfizer alone, was spent on buybacks and cash dividends to public shareholders, which increasingly include hedge funds. Meanwhile, R&D expenditures stayed flat or fell across the industry.

This is the backstory to every drug pricing scandal in memory. Between 2013 and 2015, companies owned in part by hedge funds, private equity, or venture capital firms produced 20 of the 25 drugs with the fastest-rising prices. Occasionally their role in price-gouging has received public attention. In 2015, for example, Bill Ackman of Pershing Square Fund oversaw flagrant price-inflation schemes at Valeant as part of a failed takeover of Allergen. But usually the involvement of hedge funds in price hikes goes unnoticed.

Consider the case of Mylan’s EpiPen. In 2015, Mylan controlled more than 90 percent of the country’s epinephrine injector market, with a decade left on its patents. The company’s lock on a large market with inelastic demand was chum for hedge funds; a half-dozen, notably the New York investment management firm Paulson & Company, bought stakes in the company. Mylan then started spiking the price on EpiPens, swelling revenues and inflating share price. It raised more than $6 billion off this bold display of pricing power and used the money to fund a takeover of the Swedish company Meda, just as an EpiPen two-pack hit $600. The cost of manufacturing EpiPens, meanwhile, hung steady at a few dollars, as did the sticker price of EpiPens in Europe, where regulation keeps them as low as $69.

Public outrage, most of it targeting the CEO, ensued; Hillary Clinton even tweeted about it on the campaign trail. But for Mylan, the only audience that mattered was its industry peers and Wall Street.

“Dramatically increasing prices is a honey pot for investors,” says Danya Glabau, a medical anthropologist and former biopharmaceutical consultant who has written about the EpiPen scandal. “The public expects that drug prices recoup R&D investments based on science and patient needs. But they’re shows and aspirational signals for an investor audience watching every move.”

Gilead Sciences’ new Hepatitis C drugs are another example. Although the drugs were developed in a NIH-funded lab at Emory University, Gilead was able to set the price at six-figures, leading to extreme Medicaid rationing and effectively sentencing millions of Americans to early deaths. Hedge fund manager Julian Robertson, whose Tiger Management holds an activist stake in Gilead, called the price “fabulous,” and shares in Gilead “a pharmaceutical steal.” Those drugs alone accounted for more than 90 percent of the company’s nearly $28 billion in revenues in 2016, according to its annual report.

Pricing scandals like these are often burned into the public mind with indelible images: Martin Shkreli smirking on cable news about jacking the price of Daraprim 5,000 percent, or Mylan chairman Robert Coury raising both middle fingers in a board meeting, and telling the parents of kids with serious food allergies to “go fuck themselves” if they can’t afford his $600 EpiPen two-pack. But such images tell only half the story. These scandals, and the profits they net, aren’t the work of a few “bad actors.” They are only possible because of the monopoly patent pipeline and unregulated pricing regime established and overseen by the United States government.

Although the public is constantly being lectured about the horrible “complexity” of drug pricing, solutions to the drug access crisis have been hiding in plain site for decades, in the plainly stated public interest rules attached to Bayh-Dole. These rules clearly state that the “utilization and benefits” of science developed with public funds be made “available to the public on reasonable terms.” The government not only possesses the power to directly control drug prices in the public interest—it is obliged to do so, as a condition of allowing industry access to taxpayer funded science. The government possesses the power to reduce the price on any drug it sees fit—known as “march-in rights”—and has long possessed this power.

“When Bayh-Dole created a monopoly patent pipeline from universities to the pharmaceutical industry, it also created an apparatus to protect the public from the ill effects of those monopolies,” says Gerald Barnett, the licensing expert, who maintains a blog on the history of government tech transfer.

“The law restricts the use of exclusive licenses on inventions performed in a government laboratory and owned by the government,” said Jamie Love, the director of Knowledge Ecology International, a D.C.-based nonprofit organization that works on access to affordable medicines and related intellectual property issues. “Before an exclusive license is even offered, the government must ask: Is the monopoly necessary? Whether an invention is done at the NIH or UCLA, there is also an obligation to ensure the drug is available to the public on reasonable terms.”

Of course, a long run of NIH administrators, answering to a long run of Secretaries of Health and Human Services, have chosen to ignore these requirements. “The NIH refuses to enforce the apparatus because it wants the pipeline,” Barnett said. “The lack of political will suggests the industry has bought everyone off.”

In 2017, Pharma spent $25 million lobbying Congress, up $5 million from the previous year. Among trade groups, only the National Association of Realtors and the Chamber of Commerce spent more. This has not only fostered cozy relationships between industry and Congress, but also the private sector and the NIH. In 2016, for example, at Davos, the oncologist-entrepreneur Charles Sawyers and serving NIH director Francis Collins took chummy selfies together at an announcement of Joe Biden’s Cancer Moonshot.

“When we saw those pictures, we knew we were screwed, and we were,” said Love of Knowledge Ecology International. “The government is ignoring its own directives and allowing people to die.”

This has left activists with one option: legal action. Love’s group and others have been challenging NIH, as well as researchers like Collins, in court. In April, Love’s group filed a civil action in Maryland district court against the NIH, Collins, and the National Cancer Institute, seeking an injunction against the licensing of a new immunotherapy drug developed by NIH scientists to a subsidiary of Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Love notes that there are multiple legal mechanisms on the books the government could use to drive down the cost of drugs. Along with powers enumerated in the fine print of Bayh-Dole, it can invoke Title 28 Section 1498 of the U.S. Code, which grants the government power to break patents and license generic competition in the public interest. In return, it is obliged only to provide “reasonable compensation” to the patent holder, which the government could, in the case of a price-gouging drug company, define as a platter of cold mayonnaise sandwiches. (In practice, it would likely be a bit more. During the Vietnam War, the Pentagon’s Medical Supply Agency used 1498 to procure the antibiotic nitrofurantoin for a “reasonable” reimbursement of 2 percent of the company’s sticker price.)

Is there any chance that Alex Azar, of all people, could be the first HHS chief to keep these long-ignored promises to the public? The former Eli Lilly executive does not cut the profile of people’s champion. It’s difficult to think of anyone in the current administration who does. And yet, Azar has raised the issue of patent abuses, and made noises about enforcing existing laws to stop drug makers from gaming the system and suppressing generic competition. Though unlikely, it’s not inconceivable this campaign could, if supported by enough public pressure, grow to include championing Bayh-Dole’s public interest provisions more broadly.

Whether this administration tries to solve the drug crisis, or leaves it for a future administration, any real fix will require rejecting the myth that controlling prices stymies innovation by cutting into bottom lines. The industry’s enormous profits since the 1970s—the fattest margins, in fact, of the entire U.S. economy—increasingly bear little relation to the amount it invests in R&D, and the government underwrites much of the most important research, anyway. Medicine isn’t “a business,” and the current public-private mutant beast of a system isn’t the only one capable of developing new drugs. These myths persist because of the longtime supremacy of free-market ideology in our political system, which helps explain the media’s predictable gushing over plans like MIT professor Andrew Lo’s proposal to finance the high cost of drugs, drug development and healthcare with securitized loans. (“Can Finance Cure Cancer?” a PBS Newshour segment asked in February.) Finance is the problem, and Washington alone holds the keys to the solution. Only when Americans come to terms with that, and have a government eager to act on it, will they be in position do something about the industry the president has rightly described as murderous.