In 1970, when abortion was still illegal in most states, New York passed the most liberal abortion law in the nation. The procedure became legal up to 24 weeks of pregnancy, whereas previously abortion was treated like homicide. “One of my sons just called me a whore for the vote I cast against this,” one Catholic assemblyman said at the time; his other son, he reported, urged him to change his vote. He did, and the bill passed. Three years later, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its verdict in Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion. Around 350,000 women travelled to New York for abortions between 1970 and 1973.

New York didn’t amend its law after Roe, and in time, its reforms didn’t feel very revolutionary. Abortion is still illegal after 24 weeks of pregnancy, unless a woman’s life is in danger; women who need late-term abortions for other reasons, like a fetus that’s no longer viable, must travel out of state for their procedures. It’s a precarious situation made even more uncertain by the sudden precariousness of Roe itself.

“I will be appointing pro-life judges,” Donald Trump promised in the final presidential debate with Hillary Clinton in 2016, adding that the legality of abortion “will go back to the individual states” if he puts “another two or perhaps three justices on” the Supreme Court. “And that will happen automatically, in my opinion, because I am putting pro-life justices on the court.” As president, he has kept his promise, first with Justice Neil Gorsuch and now with nominee Brett Kavanaugh, whose confirmation seems likely with Republicans in control of the Senate.

That has many worrying that Roe could be overturned in the coming years, and that abortion law will indeed go back to the states. “Women’s lives are on the line,” New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand said. “If this judge is confirmed by the Senate, the Supreme Court could take away women’s reproductive rights.”

If Roe were to be overturned, the outcome in conservative states seems clear: The Center for Reproductive Rights estimates that 22 states would ban abortion. “The threat level is very high now,” Amy Myrick, a staff attorney at the organization, told NPR. But that threat applies to blue states, too. Most states do not have laws guaranteeing a right to abortion, and a number of Democratic-leaning states have either failed to adopt measures that enshrine a positive right to abortion, or, as in New York, they recognize a limited right to abortion that’s seemingly out of step with their states’ politics. Some, like New Mexico and Massachusetts, even have archaic bans on the procedure that could theoretically come into play again.

“There are nine states that have adopted abortion protections and many of them are modeled on the standards set in Roe,” explained Elizabeth Nash, a senior policy analyst for the Guttmacher Institute, a non-partisan think tank that supports abortion rights. These laws vary from state to state. Some protect abortion access up to the point of fetal viability. Oregon’s laws are among the broadest: The Reproductive Health Equity Act, passed in 2017, requires private insurance plans to cover abortion services.

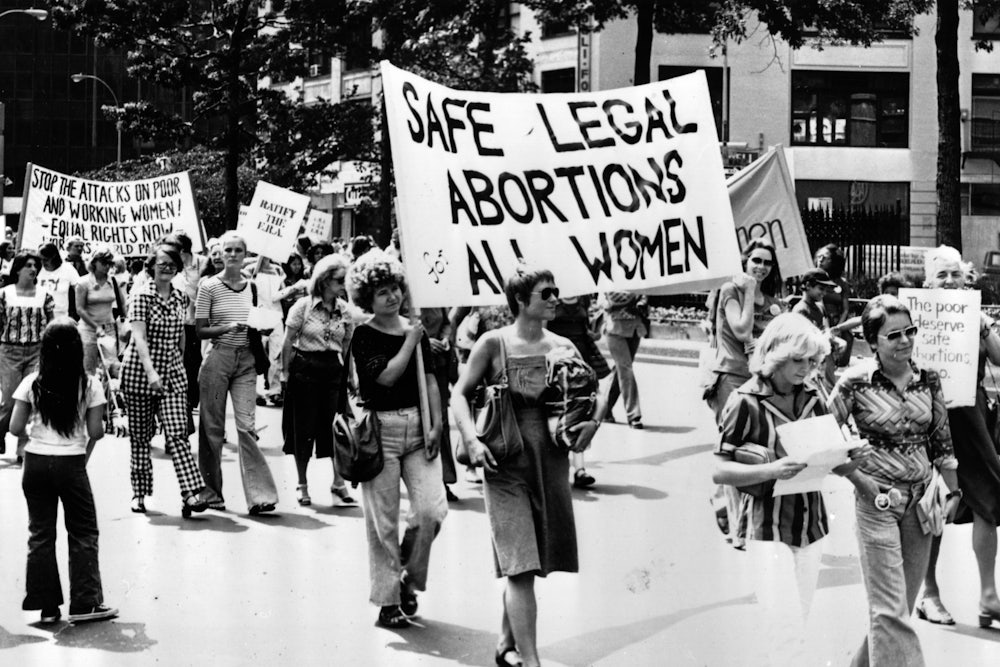

Outside those nine states, many American women would lack comprehensive access to abortion if Roe were overturned. That’s why pro-choice activists are pushing for updated abortion laws in places like New York.

“In New York, the abortion law is still regulated in the criminal code. There’s actually a first degree abortion and second degree abortion that applies to both providers and women,” Katharine Bodde, a senior legislative counsel for the New York Civil Liberties Union, told me. The 1970 law merely “carved out” an exception to the criminality of abortion, called “justifiable abortion.” The law’s limits are apparent today. According to an NYCLU report last year, “hospitals and health providers in New York are reluctant to provide abortion care to women past 24 weeks of pregnancy because of the threat that they could be criminally prosecuted under state law.”

“New York’s 24-week cutoff results in devastating denials of care,” the report added. “Women jeopardize their wellbeing to travel across the country to another state that provides the care they need–away from their friends, family and health care providers–often facing great financial cost, stress and added health risks. A low-income woman who lacks the means to travel must instead carry her pregnancy to term despite the risks, or wait to access care until her health deteriorates to the point that an abortion is necessary to save her life.”

The proposed Reproductive Health Act, which the NYCLU supports, would remove abortion from the state’s criminal code and regulate it instead as health care. It would expand exemptions from the 24-week cutoff to include fetal non-viability and risks to a woman’s health, not just her life. Current state law stipulates that abortion can only be performed by licensed physicians, but the RHA would clarify the right of physician assistants and nurse practitioners to perform abortions, either by prescribing medical abortion or providing abortion procedures.

New York legislators have introduced the RHA multiple times; it has repeatedly passed the state House, but failed to get a vote in the Senate. Governor Andrew Cuomo has long professed support for the RHA, and in a speech on Monday he blamed Senate Republicans for the bill’s failure to pass. But public pressure from gubernatorial nominee Cynthia Nixon, who is challenging him from the left, prompted Cuomo on Monday to urge the Senate, which is out of session for the summer, to reconvene to pass the law.

Cuomo isn’t the only Democratic governor racing to update their state’s outdated abortion laws. Governor Gina Raimondo of Rhode Island has also urged state legislators to convene a special session to pass the Reproductive Health Care Act, which would codify abortion rights in the state. The state’s abortion and contraception laws are uneven and some pre-date Roe. “One requires prior notice to a spouse. Another prohibits insurance coverage for an abortion. A third mandates the imprisonment for anyone who attempts to induce a ‘miscarriage’ in a pregnant woman. A fourth says: ‘human life commences at the instant of conception,’” The Providence Journal reported in February.

As she battles Democratic challengers in her race for reelection this year, Raimondo is being hounded by her own record on abortion rights. In 2015, she signed a state budget that required the state’s healthcare exchange to include plans that exclude abortion coverage. At the time, abortion rights advocates accused Raimondo of passing what amounted to restrictions on abortion access. (That year, 9,000 Rhode Islanders were automatically re-enrolled in plans that lacked abortion coverage.) Gloria Steinem and 50 other pro-choice activists cited this issue in endorsing one of her primary opponents, Matt Brown.

Massachusetts legislators are also working to update the state’s abortion laws. The state still has a nineteenth-century abortion ban on the books, in addition to laws requiring elective abortions to be performed in hospitals and banning the sale of contraception to unmarried women. Roe technically invalidated the abortion ban, and Eisenstadt v. Baird, decided a year before Roe, invalidated the contraception ban. But the Negating Archaic Statutes Targeting Young Women Act, or NASTY Women Act of 2018, would officially overturn the laws and end any chance they’d ever be enforced again. The state Senate passed the bill in January, and reportedly awaits a vote in the state House of Representatives.

In New Mexico, where Democrats control both chambers of the legislature, elected officials and abortion rights activists have renewed debate over the state’s pre-Roe abortion law. The law made it a felony for medical professionals to perform abortions unless a woman’s life was in danger, if there were fetal abnormalities, or if the pregnancy was the result of rape. New Mexico House Speaker Brian Egolf, a Democrat, told the Albuquerque Journal in June that legislators will prioritize repealing the law during their next session.

By no means is Roe certain to be overturned. The more likely scenario, as political science professor Jeffrey Segal explained to FiveThirtyEight last year, is that the Supreme Court’s five conservative justices hobble the ruling over time. “They might not overturn a precedent right away,” he said, “but they start chipping away at it until they can say, ‘Look, this precedent just isn’t workable and it’s time for it to go.” That’s why advocates like Nash, of the Guttmacher Institute, say liberals states have to act now to shore up abortion rights. “One is that we need to protect access to the right writ large,” she said. “Protecting the right to abortion may mean stepping away from the standards set in Roe.”