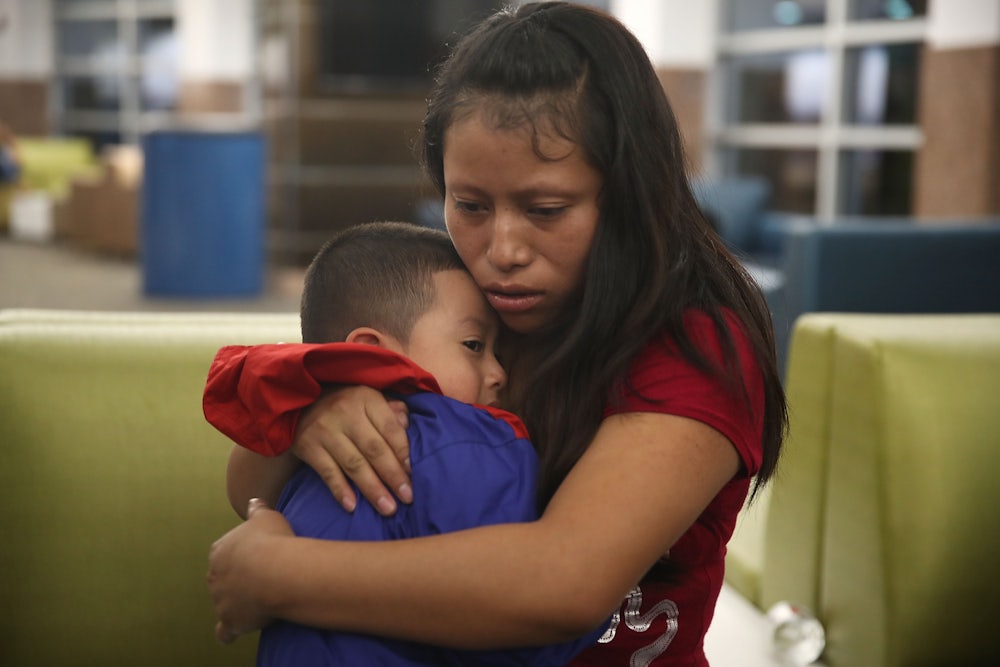

Last month, Los Angeles Times reporter Esmerelda Bermudez accompanied Hermelindo Che Coc, an asylum-seeker from Guatemala, as he was reunited with his six-year-old son. She recorded the exact moment that Jefferson met his father again after two months apart, a video that perfectly captures the human toll of the Trump administration’s migrant family separation policy. Take note of the young boy’s reaction:

Tonight, Guatemalan asylum seeker Hermelindo Che Coc was reunited w/ his 6-yr-old son, Jefferson at LAX. The two were separated at the border, didn’t see each other nearly 2 months. The boy had a vacant look in his eyes. Also a cough, bruise on his eye & rashes all over his body. pic.twitter.com/231bn1wlsN

— Esmeralda Bermudez 🦅 (@LATbermudez) July 15, 2018

Jefferson does not speak, or cry, or even hug his father back. “The boy had a vacant look in his eyes,” Bermudez wrote in the tweet that accompanied the video. “Also a cough, bruise on his eye & rashes all over his body.” In her account of the reunification, she reported that Jefferson seemed to blame his father for the experience. “Papa, I thought they killed you,” he told his father while crying. “You separated from me. You don’t love me anymore?”

Jefferson’s apparent trauma does not appear to be an isolated incident. The New York Times reported this week that children who were separated from their parents by U.S. officials earlier this year have, since reunification, “are exhibiting signs of anxiety, introversion, regression and other mental health issues.” The Times focused on one child in particular, a five-year-old Brazilian boy who “pleaded to be breast-fed,” despite having been weaned years ago, and hides behind the couch when strangers visit their home.

Other disturbing stories abound. According to migrant advocates, children have told stories of Customs and Border Protection guards kicking them while in custody and threatening to have them adopted by American families. A lawsuit alleges that children were being injected with psychotropic drugs, prompting a federal judge this week to order the government to stop doing so without parental consent. One mother alleges that officials told her daughter that she’d been abandoned and would spend the rest of her adolescence in a shelter. “When they reunited, the daughter believed that and wanted nothing to do with her mom,” wrote U.S. Representative Pramila Jayapal, to whom the mother told the story.

A federal judge intervened in July to force the Trump administration to reunite all of the separated families. As of the court-ordered deadline on July 26, the Department of Homeland Security said that 1,422 children had been reunited with their parents while another 711 children remained in its custody. A separate group of 378 children were released, to their parents or sponsors, by the Department of Health and Human Services. It’s unclear how many children have been released since that deadline or what will happen to those still in custody whose parents can’t be located.

These reunifications do not mark the end of the family-separation crisis; the real damage may only have just begun. The medical community has warned since the separation policy went into force that traumatic experiences during early childhood can lead to lifelong mental and physical ailments. “There’s no question that separation of children from parents entails significant potential for traumatic psychological injury to the child,” Jonathan White, a top Health and Human Services Department official, told lawmakers at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on Tuesday.

White left his previous job, as deputy director in the Office of Refugee Resettlement, shortly before Trump’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy was implemented earlier this year. He told the senators that he and other ORR officials had warned of the consequences of the policy, to no avail. During the hearing, Illinois Senator Dick Durbin called on Kirstjen Nielsen, the head of Homeland Security, to resign over the family-separation crisis, telling witnesses that “someone in this administration has to accept responsibility.”

Resignations alone won’t solve the problem. Nielsen’s departure, warranted as it may be, will not improve the wellbeing of the children who were traumatized under her watch. However, Congress can take more aggressive steps to remedy the injustices that have been committed: They can compensate the victims.

There are precedents in American governance for a comprehensive approach to righting wrongs. Three decades ago, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 to provide reparations to the living survivors of the Japanese-American internment camps during World War II. The statute authorized payments of $20,000 to each survivor as restitution for their internment and for the property they lost when the government sent them to the camps. More than 120,000 Japanese-Americans were interned in the camps; about 80,000 who survived until 1988 received compensation for what the U.S. government put them through.

A parallel measure also offered compensation to Alaska’s Aleut community for its treatment by the federal government during the war. U.S. officials forcibly relocated more than 800 Aleutians to internment camps elsewhere in the state and commandeered the island communities for defense purposes. Many of the Aleutians remained in camps for more than three years until they were allowed to return to their wrecked and ransacked homes. In a 2014 feature on the “forgotten internment,” the Anchorage Daily News noted that the traumatic experience led to a spike in alcoholism and that some villages never reconstituted themselves after their depopulation.

States have also occasionally sought to redress their past actions. In 1923, a white mob of rioters descended on the black community of Rosewood, Florida, destroying almost every building in the town, driving residents from their homes, and killing eight people. State officials did nothing to halt the violence at the time. Seven decades later, in 1994, Florida approved $2 million in payments for the elderly survivors of the race riot, offering a belated measure of restitution. “Our system of justice failed the citizens of Rosewood,” one state senator told his fellow lawmakers during the final debate. “This is your chance to right an atrocious wrong.”

In each of these cases, reparations came long after the original injustice. Many victims died without receiving compensation, while survivors received payment late in life. With the family-separation crisis, lawmakers have an opportunity to act more quickly, and to take a more thoughtful and targeted approach than simply offering money.

Sending reunited families back to their home countries, to face the same conditions they’d fled, would only compound their trauma. Even the constant fear of deportation is a sort of trauma. So Congress could start by passing a law that automatically grants asylum to every family that was forcibly split apart by the Trump administration.

The 1988 law that compensated Aleutian survivors of wartime internment included provisions that allowed funds to be used for medical care for children and the elderly, for historic preservation, and for improving local community centers. Lawmakers could take a similarly creative approach with the family-separation crisis. At a bare minimum, Congress could set up a fund that pays for the affected children’s medical care—including any long-term mental-health care—until they reach adulthood.

The 1988 reparation laws originated with a commission established by Congress in 1980 to study wartime internment policies and report on potential legislation. The group spent three years taking testimony from survivors across the country and reviewing government records before issuing a 467-page report. A similar commission could be warranted to provide a full and comprehensive account of the family-separation crisis alongside other restorative measures. Congress could even grant it the power to issue subpoenas for documents and testimony from recalcitrant Trump officials.

That last part—determining who contributed to this tragedy—is essential. The children harmed by the administration’s policies will likely be haunted by the experience for years to come, if not for the rest of their lives. At a bare minimum, any federal officials who participated in the systemic abuse and mistreatment of children should never be allowed to forget it, either.