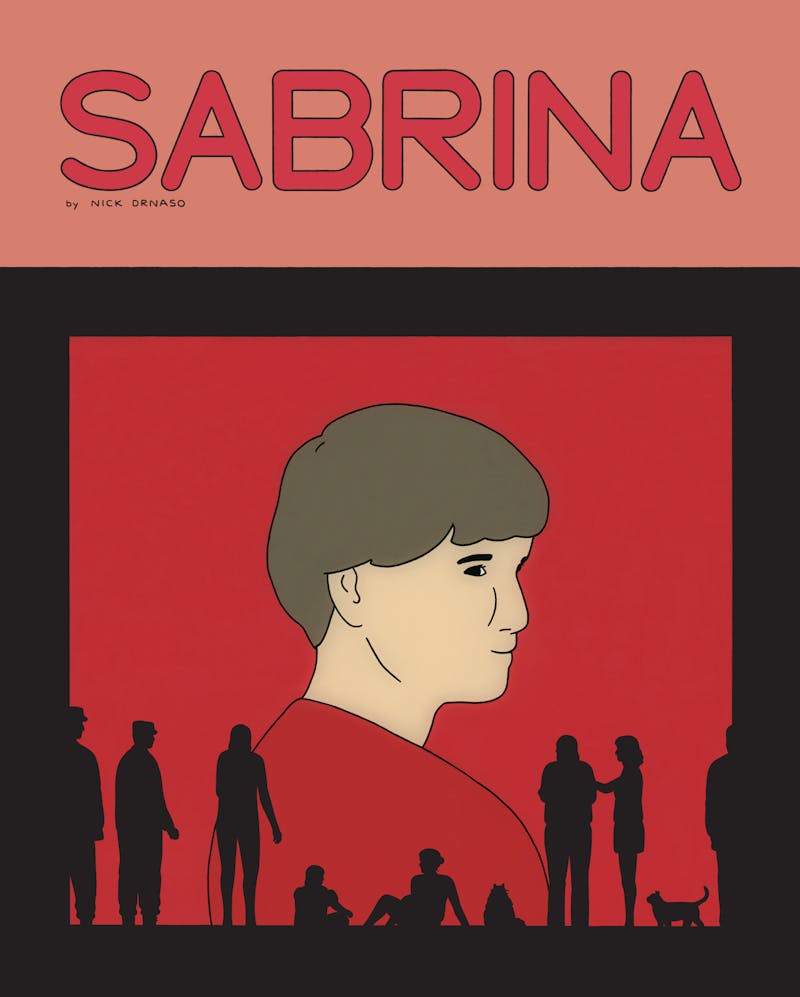

In July, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina became the first ever graphic novel to be nominated for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction. The nomination—even on the longlist—feels like an event: What kind of book using pictures would be sophisticated enough to compete with the usual Booker fare of prestige prose? A lesser work would have undermined this genre-bridging nomination, making it look like a stunt. But Sabrina—short on words, big on humanity, succinct of plot—is not a lesser work.

On the first page, we see Sabrina herself in a large top panel. Her expression is difficult to read. Like all of the characters in the book, her eyes are just dots, her mouth a line. She is reminiscent of an old-fashioned airplane safety manual person. Below, six panels show her wordlessly looking around her house for ... what? She peers down the hallway and into the bathroom and then, on the next page, under the bed—where her cat is hiding. The scene exudes the specific quiet of being home alone. Her sister, Sandra, comes over and they have an extraordinarily naturalistic conversation. “It was good to see you,” “You too,” and “See you later” all get their own panels. Then, quiet again.

There are a lot of pages without any words on them in Sabrina. No commentary, no thought bubbles.

The story that plays out across its 204 pages is simple, brief even. But the book takes its length from its pacing. Nick Drnaso moves his story at the speed of ordinary human life. In the real world, it takes about six panels to get ready for bed, and nobody talks while they do it. Events both small (conversations) and large (tragedies) do occur, but so do the many interstitial hours we spend alone, driving or just thinking. In this sense Drnaso’s scenes play out like the opposite of an old-school comic. In the work of Aline Kominsky Crumb, say, life is sped up and boiled down and whipped into crackling humor. But Drnaso takes it slowly, and that’s what makes it feel like a novel.

After the opening sequence, we turn abruptly to Teddy and Calvin. They are old friends from high school. Teddy is Sabrina’s boyfriend, we read, but Sabrina has gone missing. He’s losing his mind with stress and Calvin takes him in. Teddy stares at the wall and does nothing. Calvin brings Teddy home a hamburger every night. He works for the military in systems security, which means that each day Calvin fills out a psychological health checklist that asks: How many hours of sleep did you get last night? He has to rate his stress level from 1 to 5. He has to say whether or not he is having thoughts of suicide. It is as if the military is asking Calvin to put together a crappy comic book version of his inner life. He fills out the boxes.

Sabrina has disappeared. Then it turns out that Sabrina has been killed. Teddy stays with Calvin, Calvin helps Teddy, Sandra tries to adjust. These are small people dealing with a blow so big and so bad that it would fit better in a horror movie. Drnaso writes the murder, however, in order to trace its fallout.

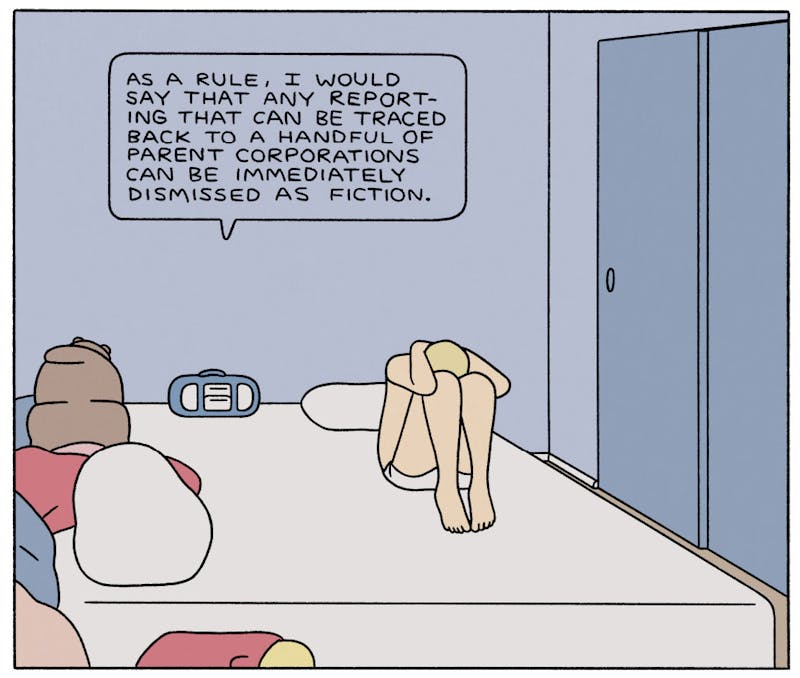

The world does something strange with Teddy’s loss. He spends his days horizontal in Calvin’s spare room. Out of a radio in that room a voice appears. He listens to the voice griping about conspiracy theories, false flag operations. He seems to find some comfort in hearing this crazy right-winger grieve for the fate of America. “Our masters will flee to their compounds, leaving us to endure unimaginable plagues and ‘natural’ disasters,” the voice laments. “Sometimes I hope I don’t live to see it.”

Sabrina’s death, unfortunately, has been both violent and captured on camera by a killer intent on turning his crime into personal notoriety. Drnaso draws websites and listicles and comment sections. He draws the way that Teddy’s personal devastation becomes just another piece of news-cycle flotsam, seized by readers eager to find some secret narrative behind the simple, sad one.

After journalists turn up at Calvin’s house to look for Teddy, an image of Calvin in his camouflage gear shows up on the internet. Online whispers flourish into full-on conspiracy theories. Was the army involved in Sabrina’s death? Did Sabrina ever exist? Calvin is subjected to Sandy Hook truther–style scrtiny, but he doesn’t really say how he feels about it. The radio that had seemed like Teddy’s only connection to the world has circled back to victimize him. We just see him lie on the ground.

The nasty conspiracy theorists of Sabrina exist outside the radio, too. Calvin’s colleague warns him against taking a mysterious new job, claiming that all kinds of “black ops” secret government terror is lying in wait for him. It’s just an expressionless drawing on a page, but the switch of this character from buddy coworker to deranged truther is frightening.

That fear comes from the way Drnaso has chosen to tell this story. These characters’ bodies act out the plot: We see where they go, what they’re doing. But their faces don’t teach us what they feel. It’s as if we are navigating a world with prosopagnosia (face blindness) and relying only on speech for clues, for patterns that give sense to the world.

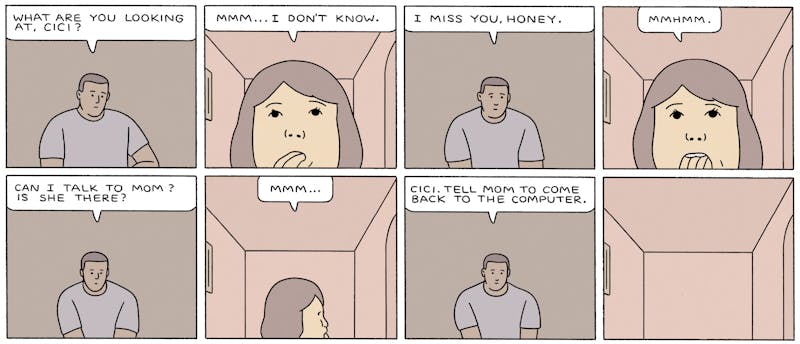

The plot stakes of Sabrina are almost lurid: abduction, murder, conspiracy. But it is a gentle book. A great deal plays out inside cars, living rooms, bedrooms. The quietest and saddest panels in this quiet and sad book are the drawings that contain no people at all, like the Skype window after Calvin’s daughter has run out of frame, or a park with nobody in it. These scenes make the difference between absence and presence very clear. A person is there, or a person is not. It’s not complicated. Death is so basic and so powerful that we think up conspiracies to impose sense on it. Sabrina is a political book, in many ways, because it looks at the madness we provoke in each other on the internet. But it is also about walking through a room and then leaving it.