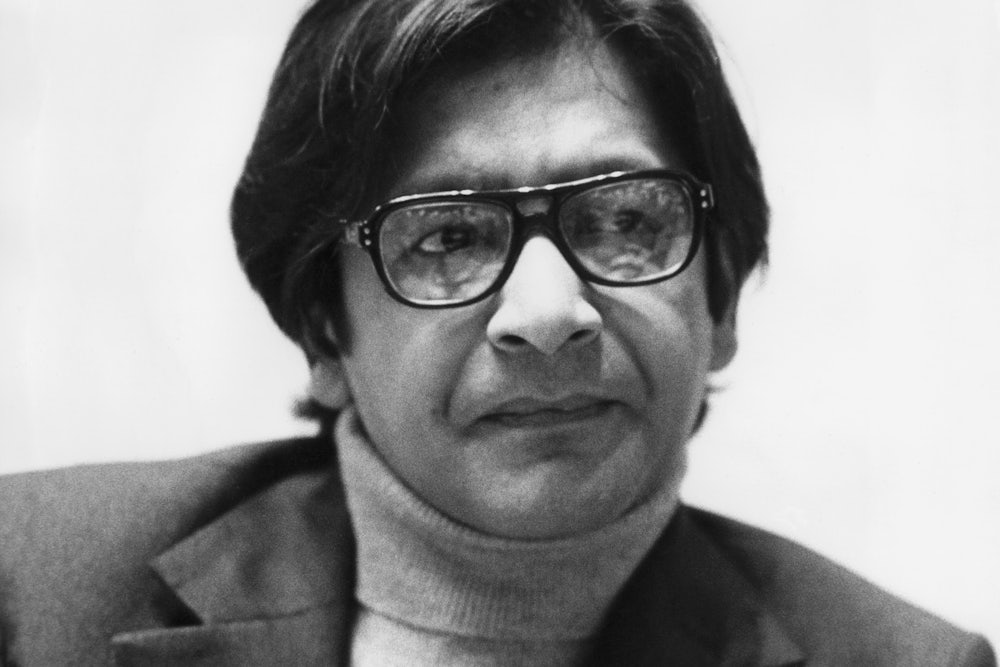

Naipaul, whose death was announced on Saturday, experienced a remarkable journey from the periphery of empire to the center of the literary canon. Yet as impressive as his rise was, his tormented relationship with his first wife and his abuse of his longtime mistress make Naipaul a prime example of the perennial and unsolvable aesthetic conundrum: how do we separate the bad actions of an artist from his or her achievements?

He was born in 1932 in Trinidad, the grandson of indentured servants who had been moved from one imperial hinterland, India, to another, the Caribbean. The family were the flotsam of colonialism, cultural castaways, the very type of people that Naipaul would make the subject of his fiction and reporting. The Naipauls were poor in money but, as Brahmins, rich in caste-pride. Seepersad Naipaul, the author’s father, was a newspaper man of literary ambition bogged down by over-bearing in-laws, the model for the main character in A House for Mr. Biswas (1961), Naipaul’s best novel.

The energy that drove V.S. Naipaul’s own ambitions came from the desire to both live his father’s unfulfilled dreams of literary greatness and avoid his father’s fate of being badgered and hemmed in by family. Naipaul moved to England in the early 1950s after he received a scholarship to attend Oxford. It was a painful migration: he was friendless and adrift in the culture, as well as marginalized by racism.

He was saved by his friendship with an Englishwoman named Patricia Hale, which blossomed into a romance. They married in 1955. “Pat became his indispensable literary helper, his maid and cook, his mother, the object of his irritations, the traveling companion who never appears in any of his nonfiction,” George Packer wrote in The New York Times in 2008. “Over the years, as Naipaul’s fame grew along with his irascibility, the marriage desiccated. If Pat overcooked the fish, he berated her and she berated herself. The couple wanted children but Pat was apparently infertile; in her passivity and shame she never pursued the possible remedies. Naipaul frequented prostitutes, which brought no satisfaction.”

It was during these years of marital unhappiness that Naipaul wrote the novels and travel books that form the basis of his literary fame. Aside from A House for Mr. Biswas, highlights of his career included An Area of Darkness (1962), India: A Wounded Civilization (1977), and A Bend in the River (1979). His global travels and keen powers of observation informed all these books, fiction and non-fiction like. In them he became the heir of Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene, a truly global writer who had the rare gift for capturing the texture of many societies.

Naipaul’s best books are animated by his deeply conservative social vision. Civilization, he felt, was a small clearing in a forest, a fragile haven that was always on the verge of reverting to the wild. It was Naipaul’s gift to be able to convey this fear in wire-taut prose.

The fragility of civilization was something that was true not only of the world at large but evident in the private lives of individuals. The critic Walter Benjamin once wrote that “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” These words might stand as an epitaph for Naipaul’s life and work.

To the outside world, Naipaul was an emblem of civilization: an Oxford graduate, author of many prize-winning books, and, after he was knighted in 1990, titled nobility: Sir V.S. Naipaul. His treatment of the women in his life belied this image of cultivation.

As his literary career blossomed, his personal life remained troubled. In 1972 he entered into a long-term romantic affair with Margaret Gooding, an Anglo-Argentine woman he met in Buenos Aires. If Naipaul had the habit of psychologically tormenting his wife Patricia Naipaul, he took to physically assaulting his mistress. “I was very violent with her for two days with my hand; my hand began to hurt,” Naipaul once told is biographer Patrick French. “She didn’t mind it at all. She thought of it in terms of my passion for her. Her face was bad. She couldn’t appear really in public.”

In 1994 when Patricia Naipaul was struggling with breast cancer, her husband gave an interview with The New Yorker where he said that he had been a “great prostitute man” and only found sexual pleasure with his mistress, Gooding. Patricia Naipaul was devastated by the interview. She died two years later.

“It could be said that I had killed her,” Naipaul admitted to his biographer. “It could be said. I feel a little bit that way.”

After Patricia Naipaul’s death, the novelist broke off relations with Gooding. He married the Pakistani journalist Nadira Khannum Alvi in 1998. She survived him.