If you designed a job to embody a kind of old-school masculinity, you couldn’t do much better than orca capture, which combines elements of hunting, fishing, rodeo, and unfettered capitalism. Chasing, corralling and trapping these giant predators of the sea requires a certain toughness: In the course of a whale hunter’s career, he might harpoon a juvenile and tow it by boat, or separate a crying baby from its family, or use the cries of the baby to lure the rest of the family into a trap. But the old salts in this business end up reflective and teary, because upon closer contact, it turns out their prey are smart and social animals who behave gently and tenderly toward each other and the humans they bond with.

We already know this about orcas, of course. And we know it largely because of the orca display industry, which showed us decades of these giant dolphins interacting with humans, doing tricks, exhibiting levels of intelligence and emotion close to our own. Boomer children met Shamu, SeaWorld’s first performing orca, in the mid 1960s; millennials had the 1993 film Free Willy, which spawned three sequels, and made its killer-whale cast member, Keiko, a star. A campaign sprung up around the idea of giving Keiko, who had spent two decades in a small tank in a Mexican amusement park, the same freedom as the fictional Willy, and in 2002 Keiko was released in Iceland.

A turning point for the industry came in 2013 with the documentary Blackfish, which told the story of Tilikum, an orca that killed a trainer at SeaWorld in Florida. It offered a grim view of Tilikum’s life—spent isolated from others of his species, without the social bonds of a wild pod, confined to a pen where he swam in tiny circles for so long that his dorsal fin flopped to one side—and of the orca-display industry in general. We had learned from captive orcas that the species was incredibly smart and social; Blackfish argued that these very qualities made them suffer in captivity. After the film’s release, public opinion turned against marine parks, particularly SeaWorld, which reported an 84 percent drop in profits in 2015.

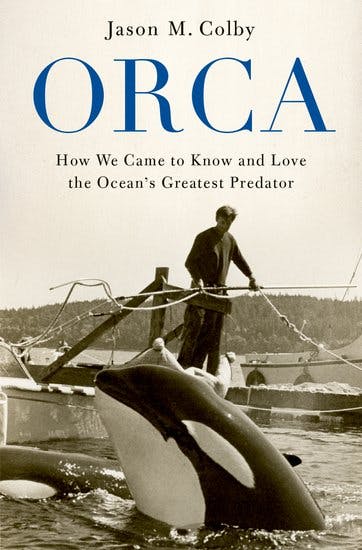

Jason M. Colby chronicles this rise and fall in his book, Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean’s Greatest Predator, beginning with a time when killer whales were still viewed as monsters and pests. Much of the action centers on the 1960s and 1970s, when the systems that led to the Tilikum tragedy were being put into place. It is a story not just of the orca business, but also of the evolution of Americans’ relationship to the oceans and marine life—the growth of marine parks parallels the shift from an extractive approach to the ocean, as mainly a source of fish, to a recreational one. It intersects, too, with the birth of the modern environmental movement in the 1960s and 70s, a time when Greenpeace was campaigning to “Save the Whales” and one of its leaders, Paul Spong—who, makes cameos in Colby’s book as a young researcher—would play his flute to the captive whales.

For a generation that grew up on Shamu or Free Willy, anecdotes that Colby shares of orca hunters in “the Old Northwest” are shocking. The orcas then were seen as competition; hunters and fisherman would shoot up pods of orcas because they were eating up the salmon or seals that the fishermen wanted for themselves. Some of these stories date from the late 1800s and 1910s; but as late as the early 1960s, orcas had a reputation as a dangerous nuisance. “They ought to bomb all them dumb whale out of here,” says one Washington fisherman in 1962, “use them for target practice.”

The book’s main character, Ted Griffin, grows up in this “rough and tumble” environment. Colby paints the young Griffin as a “Tom Sawyer of Puget Sound,” who loved the sea and animals. He was, as a teenager in the late 1940s, one of the first scuba divers in the Salish Sea, after ordering an early iteration of Jacques Cousteau’s new contraption, the Aqua Lung. Around this time, the economy in the Pacific Northwest was changing, drawing workers into cities and office jobs, away from extractive industries, and, as Colby puts it, “the shared world of fishermen and orcas was changing.”

In the new Northwest people like Griffin with his diving gear started looking to the ocean for recreation and not just resources. In 1961, he had a close encounter with a pod of orcas. He saw them “nosing around in a kelp bed” near his home and rowed out to take a look. A large male orca dove under his boat and rolled onto his back, looking up at him. As the pair stared at each other, Griffin underwent a transformative moment: “Mesmerized,” he “imagined swimming alongside the graceful creature, breaking down barriers between species.”

Griffin pursued his dream of connecting with killer whales, but it wasn’t all inter-species eye contact. The first orca Griffin procured, Namu, was caught accidentally by some fishermen, when a snagged fishing net trapped a pair of orcas between a reef and a rocky outcropping. There was a passageway out of the net, and Namu, the bigger orca, tried to nudge the younger one (likely his sibling) out through the hole. When this failed, he swam in and out himself, demonstrating how to get out. But the baby wouldn’t follow, and rather than leave him alone there, Namu stayed. It took Griffin a few days to get to the whales; during that time, other members of the pod congregated outside the net and called to the ones trapped inside. The younger orca did eventually escape, but it was too late for Namu. Griffin bought him for $8000, delivered to the fishermen in small bills that he’d borrowed from a collection of friends and neighbors.

From that moment on, Griffin’s career—and his relationship with the whales he loves—was full of contradictions, which often reflected the tensions at the heart of the entire display industry. Griffin was driven by his desire to connect with the animals. As he constructed Namu’s harbor pen, swimming with the animal in a wetsuit, Namu chirped at him, and mimicked the sounds that Griffin made into his diving mask. The orca’s desire to communicate moved Griffin to tears, even as he continued working on its cage.

“I wanted Namu to be free,” Griffin told Colby, years later, “but couldn’t part with him.” Griffin and Namu did bond, and Namu earned a reputation as a “gentle giant”; Griffin would swim with him and ride on his back and never came to harm. “By all accounts, Namu was a sweet soul,” Colby writes, noting that orcas have unique personalities and that “Namu clearly came to relish close contact with his owner.” They are also social animals, and its perhaps unsurprising (now) that an orca separated from its podmates and kept in isolation would seek out other bonds where it could.

Griffin’s career progressed in parallel with the industry itself. It was Griffin who caught Shamu, the first healthy orca ever captured intentionally. (He was a major player in the orca-capture business but, it should be noted, certainly not the only one.) Shamu (short for “She-Namu”) was supposed to be Namu’s “bride,” but when Griffin introduced her, she seemed to hate both Namu and Griffin, and to especially hate the bond between them. She would knock Griffin off of Namu when he rode the whale, and was aggressive toward them both. Maybe she was holding a grudge; she was captured as a juvenile and her mother died in front of her in the course of the capture. In 1965 Griffin sold her to SeaWorld, where she became a celebrity. Though the original Shamu died in 1971, SeaWorld continued to use “Shamu” as a stage name for the orcas in its theatrical shows for decades.

As the years pass, there is so much violence against orcas that the incidents start to blend together. A captive orca is dropped on its head during a transfer and soon dies. Another crashes through the glass of a window in its display tank. Many are harpooned; one is harpooned on a line that’s connected to a helicopter, with the idea that the helicopter would eventually tow it to shallow water for capture; instead the animal dives deep, swimming so strongly it pulls the helicopter down with it.

And what accumulates, too, is a new way of seeing and thinking about these animals. People learn that they are clever, and that they take care of each other. Time and again, they work together to hunt, or to try to escape humans; they hang around one another when one is captured but not removed from the water; they form bonds with one another and with humans. During one capture, when several orcas are corralled in a harbor, a thousand people show up to watch—“I was actually quite sad about the whole thing,” one of the captors recalls. “The whales were crying when you got one up on the dock and the other ones were crying in the water.” As the backlash against the industry rises, the irony is clear: The captivity and display industry made people love orcas, and then hate the captivity and display industry.

This is the central thrust of Colby’s book, and he returns to the point throughout, wondering how history should remember Griffin and his colleagues. Colby’s father was involved in a few captures, and later talks about them regretfully. How should readers think of him? It is an interesting question, but ultimately not as knotty a conundrum as the book makes it out to be—norms change, the culture changes, hopefully toward what’s more compassionate and humane. Plenty of behaviors that are now reviled were once not just legal but perfectly ethically mainstream. We can see such changes, know them to be just, and also understand that people used to operate with values, perhaps with different knowledge. With any luck, in half a century, some of our own activities will also be deemed too cruel.

More interesting, to me, than the judgment of history, are the moral compasses of the crying men themselves, who knew—well before Greenpeace protestors and Blackfish and the Marine Mammal Protection Act—that the animals they were hurting were sentient and sensitive; that they were doing something wrong. Griffin talks throughout the book about a shift he underwent: from a boy who loved whales to a man who was in the whale business. As save-the-whales rhetoric rose up around him, he grew bad tempered. He dove into libertarian politics, angry at the shift in environmental norms that suddenly made him into a bad guy. Colby writes that when Griffin had started out, “the live capture of a killer whale seemed the antithesis of commercial whaling; now many viewed them as one and the same.”

Griffin later wrote that the regulations on whale-capture represented “the loss of one of my highest values, my freedom … the freedom to live and enjoy life to the fullest.” It could be, if pointed another direction, the exact language of an anti-SeaWorld activist. The story of the sad sea cowboys is one of shifting mores, sure. But it’s also a story of the intellectual hoops that we humans will jump through, like well-trained marine mammals, in order to justify the harm done in the course of making a living, or just doing whatever we want.