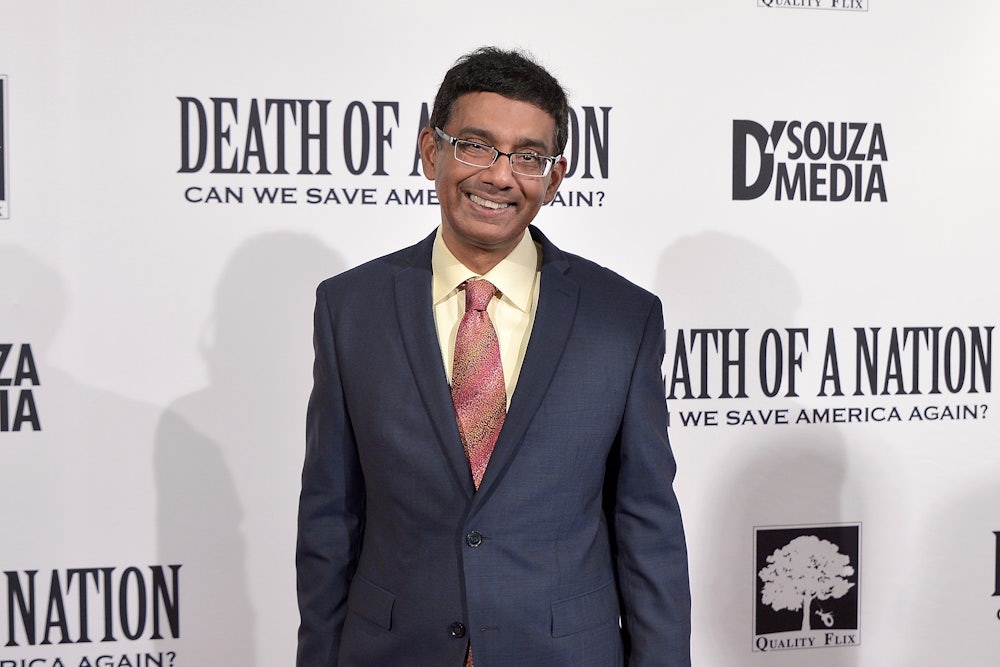

In a deeply reported and nuanced profile in The Weekly Standard, Alice B. Lloyd asks how Dinesh D’Souza went from being “one of the cleverest polemical journalists on the right” to his current status as a clownish provocateur whose antics often embarrass serious conservatives.

In answering this question, Lloyd hits the highlights of D’Souza’s colorful career: his student days at Dartmouth College where he pioneered a form of right-wing tom foolery, his bid to be a serious journalist writing about political correctness in his book Illiberal Education (1991), his overt hostility towards African-Americans displayed in his book The End of Racism (1995), his move towards a more popular audience in demagogic documentaries and polemics such as The Roots of Obama’s Rage (2010), his scandal-plagued tenure as president of King’s College, the extramarital affair which ended his first marriage and also entangled him in an campaign finance violation which led to becoming a convicted felon in 2014, his dubious redemption by a politically motivated pardon from President Donald Trump, and his current status as one of Trump’s foremost advocates.

It’s been a wild ride for D’Souza. Lloyd convincingly argues that in this case the boy was the father to the man: The nature of the mature D’Souza was already evident in his formative years as a Dartmouth undergraduate.

As Lloyd writes:

D’Souza’s rhetorical tactics may be perfectly suited to the Age of Trump, but he learned them long ago: at Dartmouth College in the early 1980s, where he led the Dartmouth Review, the country’s best-known conservative campus paper. “American politics has caught up with Dartmouth,” he tells me. The Review’s undergraduate antics—outing the officers of the Gay-Straight Alliance, printing an affirmative action op-ed in Ebonics, hosting a lavish luncheon alongside a fast for world hunger—readied him for Trump: “For 20 years, I wasn’t doing it. Because for 20 years, American politics wasn’t like this.” D’Souza, 57, sees himself as a pioneer of the puerilizing of political discourse.

This is a highly persuasive argument. Not just D’Souza but an entire cohort of young right-wingers were formed by the campus wars of the 1980s, a milieu that rewarded prankish provocateurs. This was the environment that produced not just D’Souza but also Laura Ingraham (a fellow Dartmouth student) and Ann Coulter (who carried on in the same fashion as D’Souza and Ingraham at Cornell).

One could quibble with Lloyd about whether even in his best days D’Souza was all that rigorous. While it’s true Illiberal Education was praised by some centrists, Louis Menand’s New Yorker review found the book to be unconvincing and glib. But it’s fair enough to say that in the late 1980s and early 1990s, D’Souza made a greater effort to be a serious writer. The general message of the profile, however, is that for most of his life the Dartmouth D’Souza has been the dominant one. D’Souza has remained a permanent sophomore.