Donald Trump may threaten his political enemies with tweets, but he has nothing on antebellum congressmen. In the three decades before the Civil War, members of the House and Senate routinely threatened each other with violence, and often acted on it too. They brawled on the House floor; they faced off in duels; they fired shots in Congress. They beat each another senseless with canes. All told, members of Congress engaged in at least 80 acts of physical violence between 1830 and 1860, a remarkable fact uncovered by Joanne B. Freeman, a historian at Yale, in her superb new book The Field of Blood. With Congress unable to solve the problem of slavery without resorting to violence, she argues, war became the only option.

Much of this violence remained hidden because Congress wanted it that way. Not until the late-1840s did independent journalists cover congressional debates regularly, Freeman explains, and officials scrubbed clean the published reports of floor debates in order to make Congress look more dignified. But dignified it was not. Freeman unearths its tumultuous nature by reading through the unpublished papers of many political figures, and one in particular: Benjamin Brown French. The House clerk through much of the 1830s and 1840s, and later a Republican Party organizer, French kept meticulous diaries that provide a rare glimpse into the daily workings of Congress.

One of Freeman’s main contentions is that, before the 1840s, congressmen tended to fight along party lines, not sectional ones, and the major parties were cross-sectional. Take the 1838 duel between Jonathan Cilley, a Democrat from Massachusetts, and William Graves, a Whig from Kentucky. Though they were from different sections, the duel emerged after James Webb, a Whig editor from New York, charged Cilley, and by extension all Democrats, with corruption. Cilley demanded an apology; Webb refused, then challenged Cilley to a duel. It was beneath the dignity of congressmen to duel lowly journalists, so Graves, a fellow Whig, stepped in for Webb. In truth, neither one wanted to duel, Freeman writes, but their parties were egging them on. When, on February 24, 1838, Graves’s bullet killed Cilley instantly, everyone was shocked; many were angry. But French, then a Democrat, captured the feeling of many in his party when he wrote that he was proud of Cilley for facing death with “an unflinching eye.”

This increase in violence gave southern congressmen a distinct political advantage: Unlike their southern counterparts, northern congressmen were rarely rewarded for fighting because northern voters tended not to vote for belligerent representatives. One of Freeman’s more intriguing arguments is that the threat of violence helps explain why southern congressmen were able to protect slavery for so long. She devotes a particularly good chapter to the “gag rule,” which barred antislavery petitions from being read on the House floor, and lasted from 1836 to 1844. Anytime an antislavery congressman challenged the rule, a proslavery congressman would threaten him with violence; northern representatives were helpless, since challenging them would have meant losing their seats.

In 1842, Edward Black, a proslavery representative from Georgia, threatened to lynch an antislavery congressman, John Giddings of Ohio, for challenging the rule, then ran at him with a cane when he refused to stop. A year later, John Dawson, a proslavery Louisiana congressman, threatened to cut the throat of another gag rule-breaker, calling him “a d—d coward’ and a d—d blackguard.” Indeed, two of the five most violent congressional brawls happened during the gag rule period, Freeman finds, both instigated by southerners.

But the violence of the gag rule eventually backfired. As debates over slavery came to dominate national politics in the 1850s, northern voters increasingly favored politicians who showed a willingness to fight back. They saw southern belligerence as a threat to free speech, a right northerners now embraced with as much fervor as southerners did their right to own slaves. In the decade before the Civil War, free speech became a “sacred right” to northerners, Freeman writes, one that southern congressmen, with their constant bullying, threatened to destroy.

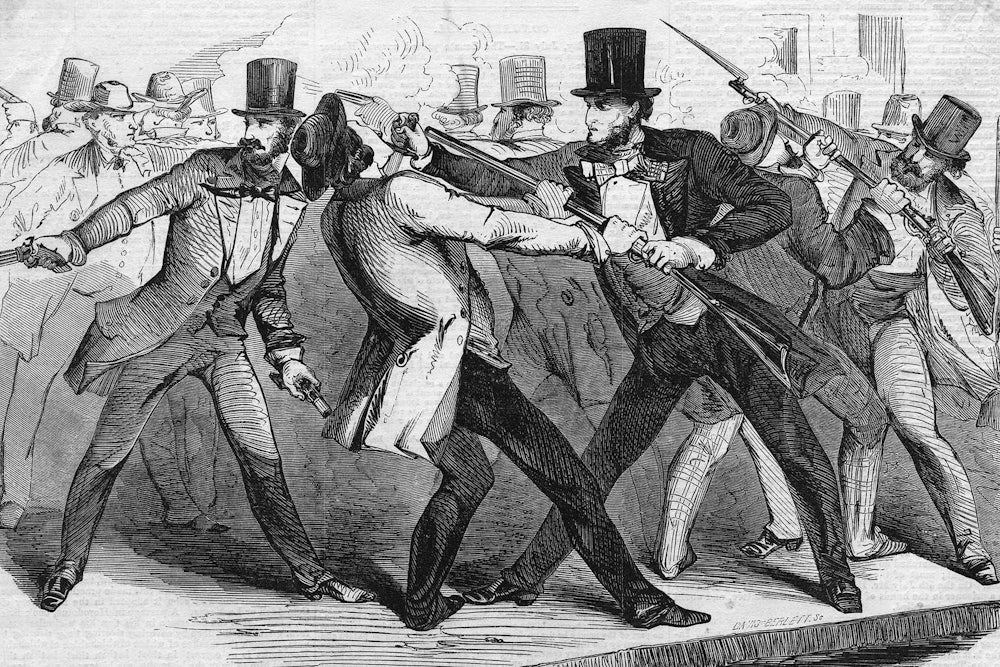

The most popular northern congressmen from the mid-1850s to the Civil War were ones who refused to be silenced, and were willing to throw punches if need be. Readers might remember the 1856 caning of Charles Sumner, the antislavery senator from Massachusetts who was beaten unconscious by Preston Brooks, a proslavery South Carolinian. But they probably never heard of the eight other fights that broke out between congressmen, or between congressmen and journalists, in the two years surrounding Sumner’s caning. Freeman uncovers all these and more, from the January 1856 assault on Horace Greeley, the antislavery editor of the New York Tribune, by the proslavery congressman Albert Rust, to the February 6, 1858 “battle-royal in the House,” as one congressman called it, which pitted antislavery Republicans against proslavery Democrats.

There were a few key differences between the fights of the 1850s and the 1830s, Freeman writes. Most importantly, from the 1850s onward, fights were almost always sectional, and almost always about slavery. The Republican Party, founded in 1854, was concentrated in the North and congealed around a moderate antislavery platform. That stood in contrast with the cross-sectional Whig and Democratic parties of the Cilley-Graves era, whose fiercest divisions were over tariffs and banks. Second, most of these new northern Republicans were, for the first time, willing to fight back. They almost never threw the first punch, but their strident antislavery remarks provoked many a southern congressman to race down the aisle with fists blazing, and on most occasions, northern congressmen blazed their fists back.

Finally, the press increasingly fueled congressional fighting. By the 1850s, editors realized that, by giving prime coverage to the nastiest verbal insults, and by covering as many actual fights as possible, they could sell newspapers. “By portraying Congress as an institution of extremes,” Freeman argues, “the press downplayed the appeal and even the possibility of compromise.”

Freeman has written a smartly argued, diligently researched, even groundbreaking book. But many readers will put down Field of Blood with the impression that the Civil War could have been averted had only the nation’s elected officials acted more cordially toward each other and learned to compromise. Academic historians have long debated this exact issue, with one side arguing that the nation had become so polarized over slavery that war was inevitable; the other that, had we had more capable statesmen, war could have been averted. Freeman avoids picking sides, but her book closely aligns with the latter camp. Yet one of the problems with this line of thinking is that, in emphasizing the tragedy of the war, it downplays what the war accomplished—emancipation—even if unintentionally. It also obscures the fact that politicians had already been compromising over slavery—and the public was no longer accepting it.

As Freeman documents, the most intense congressional violence came amid far more intense violence outside the halls of Congress. Almost always, these civilian clashes were a response to the very compromises Congress had struck. For instance, when Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Act as part of the Compromise of 1850, abolitionists refused to accept it. They set up Vigilance Committees to protect fugitive slaves and legally free black people from capture, often fighting off the slave-catchers sent to retrieve them. When, in 1854, Congress again reached a compromise, this time by allowing the residents of Kansas to determine themselves if their state should be slave or free, proslavery militias and antislavery militants engaged in some of the bloodiest civilian violence the nation had ever seen. Between 1855 and 1858, 52 people had been murdered in Kansas, 36 of them antislavery advocates, and five of them proslavery diehards killed by John Brown. And that was before his raid on Harper’s Ferry.

Freeman is certainly right that congressional violence didn’t help matters. And as a political parable for today, Field of Blood works well. But readers shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that well before our elected officials turned on each other, average Americans had already done so. Few understood this better than black abolitionists. Many of them had lived through the violence of slavery, and they knew that once that violence became better publicized, as they made sure it would be, the nation’s yawning divide over slavery would arouse passions that perhaps no politician could suppress. In that case, they’d be ready to fight in a war they had long seen coming: “Sooner or later,” the black abolitionist John Rock predicted in 1858, “the clashing of arms will be heard.” “Will the blacks fight? Of course they will,” he continued, “when the time comes, and come it will.”