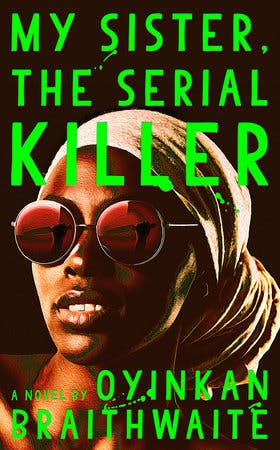

Korede, the narrator of My Sister, The Serial Killer, the debut novel by Oyinkan Braithwaite, is a nurse at a hospital in Lagos, the city where she lives with her mother and her sister, Ayoola. The sister is the beautiful one; Korede is clever. “Ayoola looks like a Bratz doll and I resemble a voodoo figurine,” Korede jokes. Beyond looks, there is one key difference between the sisters, however: Ayoola is killing people.

Specifically, Ayoola is killing men. When we first meet the sisters they are in the act of disposing of Femi, who was Ayoola’s boyfriend. This isn’t the first time Korede has been recruited to help Ayoola out. Being a nurse, she is fastidious about cleanliness and can clear up a crime scene. Both sisters were oppressed by a violent father, now dead, and as adults they are locked into a dyad of mutual protection riven by jealousy and rancor. Korede resents Ayoola deeply—she gets away with everything, being so careless and so very beautiful—but she has to keep her safe.

You could read My Sister, The Serial Killer in an afternoon. Braithwaite’s writing pulses with the fast, slick heartbeat of a YA thriller, cut through by a dry noir wit. That aridity is startling, a trait we might expect from someone older, more jaded—a Cusk, an Offill. But Braithwaite finds in young womanhood a reason to be bitter. At the center of these women’s lives is a knot of pain, and when it springs apart, it bloodies the world.

The most readily apparent source of that pain is the tension between the two sisters, which revolves around beauty and sexual charisma. Korede works with a physician called Tade, and she’s angry when Ayoola seduces him with her offhand charm. One day Tade sends a bouquet of orchids to Ayoola. “Is this how he sees her?” Korede asks. “As an exotic beauty? I console myself with the knowledge that even the most beautiful flowers wither and die.”

By loving Ayoola, Tade has put himself in danger. Korede can never quite figure out why Ayoola is killing the men she dates. Some are grotesque or violent, but Femi, for example, didn’t do anything wrong. Ayoola displays no remorse whatsoever. She keeps trying to post cheerfully to Snapchat, and Korede has to explain that it will seem distasteful to act so blithely so soon after Femi’s “disappearance.” But Ayoola is right in the end—nobody cares. “#FemiDurandIsMissing” causes a minor stir online, but is quickly forgotten.

It’s this shallowness in Nigerian society writ large that Korede seems to hate most of all. She can’t stand the hypocrisy of men who claim to know Ayoola’s soul when all they see is her face. She can’t stand the auntie who advises her nieces to keep their “hair long and glossy or invest in good weaves” so they can hold down a man.

In Korede’s mind, all these indignities come together. Ayoola’s unearned adulation, the cops who extort her at traffic stops, the petty auntie: they’re all part of the same corrupt order. This knowledge has made her intelligent, wiser than her friends and family, but also angry and alone. “I know better,” she spits about her aunt, “than to take life directions from someone without a moral compass.”

Korede is seemingly beset on all sides. In the hospital where she works, however, she can exercise autonomy. She commands her orderlies to scrub the windows better, as if by purifying her workspace she can eliminate the silt of dishonesty from the world. Worse, she uses her status at the hospital to belittle others. If Korede is powerless in her own home, always blamed for Ayoola’s mistakes, in the hospital’s white wards she can mock a man who smells bad and deride the junior nurses. Power corrupts, Braithwaite implies—even when there’s a lot of bleach on hand.

For Korede, the relationship between power and corruption is ingrained. She sometimes longs for the hated dead father, a wealthy blowhard fond of beating his children with a cane. He knew how to cut a deal, and Korede knows that his skill with corruption would have done away with all of Ayoola’s dirty deeds. But his sins implicate the children as well. “He could do a bad thing and behave like a model citizen right after,” she thinks. “As though the bad thing had never happened. Is it in the blood? But his blood is my blood and my blood is hers.”

Here is the paradox of being young: Am I my blood, or am I my choices? It turns out the deepest and tightest knot of all is identity. Braithwaite’s portrait of Lagos, with its seedy corruption and choking traffic and rigid family norms, makes that search for identity feel even more stifled, more predetermined. It is a portrait in pain, but also in a dark kind of humor. In one scene, Ayoola comes back from a jaunt with one of her beaux. How was it? Korede asks. Ayoola replies, “It was fine ... except ... he died.”