For three consecutive days in April of 2001, a then 27-year-old Monica Lewinsky sat on the stage of New York’s Cooper Union auditorium, answering questions from a packed audience composed of law students and graduate students in women’s studies and American history. Lewinsky and a team of two documentarians—Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, the founders of World of Wonder Productions, the company behind Party Monster, Inside Deep Throat, The Eyes of Tammy Faye Baker, and more recently RuPaul’s Drag Race—stocked the public Q&A with a thoughtful crowd and then informed them that they had permission to ask her anything. For the first time, she was legally allowed to speak publicly not only about the Clinton affair, but also about Linda Tripp, who secretly recorded Lewinsky talking about her interactions with the President and then slipped those tapes to Kenneth Starr’s team.

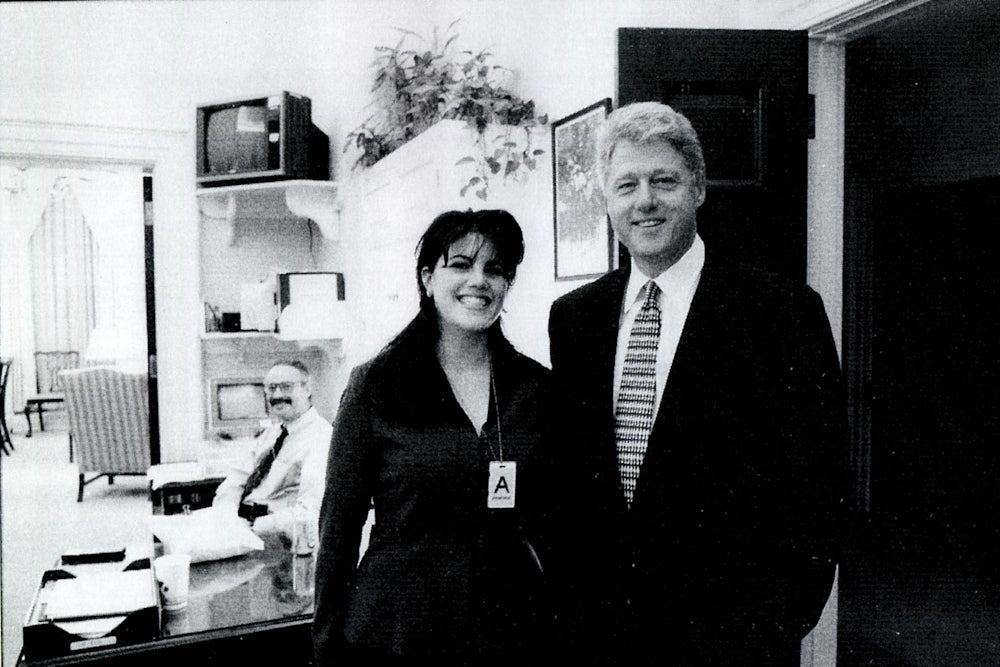

Lewinsky fielded questions for over ten hours during three filmed sessions, which Bailey and Barbato then cut into the 95-minute HBO special Monica in Black and White, which aired on the cable network in early 2002. The title of the documentary (which you can now find on YouTube) refers to both Lewinsky’s outfit—she wore a black pantsuit and white button down shirt—and the fact that the film is not in color (lending a patina of gravitas to the whole undertaking). But it is also a knowing wink: Lewinsky’s story is and has always been a cultural gray area, and a moving target. Since the news broke of Bill Clinton’s affair with a 22-year-old White House intern in January 1998, Lewinsky has been called many things in the media: a victim, a seductress, a punchline, a heroine, an innocent, a vamp, a feminist icon, a camp icon, a cautionary tale, an inspiration.

The “real” Lewinsky was, of course, lost in all of this, even as projects like the HBO documentary attempted to show her unfiltered truth. When Monica in Black and White first aired, a New York Times reviewer (a woman, I might add) called it “Monica The Infomercial,” and argued that it “panders to Ms. Lewinsky’s image-reconstruction project…. She comes across as someone who is trying hard to invent a new image but isn’t very good at it.” The reviewer runs through a laundry list of Lewinsky’s public appearances (the Herb Ritts shoot for Vanity Fair, the Jenny Craig ads, the big Barbara Walters interview) and sneers that “with every public relations gambit she becomes less sympathetic.” This lingering disdain prompts a lingering question: What was Lewinsky supposed to be doing instead? She stated several times that she never wanted to become a public figure, that she never wanted her name splashed across 60 Minutes or turned into a parodic jingle on the Howard Stern Show. But once the Tripp tapes aired on C-Span and Congress voted to release the Starr Report online in its entirety, Lewinsky didn’t have a choice. She could try to disappear (which she did, for several years following the HBO special) or she could try to show her side of the story.

When Lewinsky made the television special in 2002, her story still felt very raw, and she—understandably—didn’t seem to have much distance from it yet. When she first sat on stage, she told the audience that she was “very nervous” and she rocked back and forth in her seat. At one point, she sits directly on the stage floor, with her legs crossed into a pretzel front of her, curling herself up into as small a shape as possible in the face of the verbal barrage. She is able to defend herself (one man stood up to say he found the entire evening distasteful, and she cooly shot back, “Why did you come here tonight, sir?”), but she also pauses often to hang her head in her hands, overwhelmed by the requests to recount her humiliation over and over. At one point, someone in the back of the crowd shouts “We’re on your side, Monica!” and her sigh of relief is palpable. For Lewinsky, nothing at the time was black and white; it is clear she was wandering around in a haze, trying to make sense of what had happened to her and how her public and private selves had become so bifurcated.

Sixteen years later, Monica Lewinsky, now 46, is again telling her story on television, this time as one of several interviewees who sat for a new six-part documentary from director Blair Foster, called The Clinton Affair, which airs over three nights this week on A&E. This time, her interviews are in full color. She wears a pink blouse, the color of California bougainvilleas, and speaks with a composed confidence; she seems to know that she is releasing her story into a far different world this time around.

Since returning to the spotlight with a Vanity Fair essay about weathering public shame in 2014 and a viral TED Talk in 2015, Lewinsky has managed to wrestle back some measure of control over her side of the narrative. She now regularly contributes to Vanity Fair, placing her experience in the context of the #Metoo movement, and this year, she promoted an anti-bullying campaign that involved celebrities briefly changing their Twitter display names to the public slander that had hurt them the most (Monica changed hers to “Monica Chunky Slut Stalker That Woman Lewinsky”). She has begun to align herself with historical feminist agitators, such as the activist and poet Muriel Rukeyser—in an essay about why she chose to participate in the A&E documentary, Lewinsky wrote,

Rukeyser famously wrote: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.” Blair Foster, the Emmy-winning director of the series, is testing that idea in myriad ways. She pointed out to me during one of the tapings that almost all the books written about the Clinton impeachment were written by men. History literally being written by men. In contrast, the docuseries not only includes more women’s voices, but embodies a woman’s gaze.

Lewinsky seems to not only have found her voice, but also her people: She doesn’t have to carefully select rooms full of Women’s Studies majors to find a sympathetic audience. Though the director of The Clinton Affair interviewed dozens of talking heads from all sides of the scandal (Kenneth Starr, James Carville, Bob Bennett, David Kendall, Lucianne Goldberg, Lewinsky’s parents and close friends—the only notable absences are Tripp and the Clintons themselves), the show’s sympathies lie with Lewinsky as it highlights the hideous ways that the media raked her over the hot coals of judgment. One particularly effective segment comes in episode 5, as Foster puts together a maddening montage of various late night television hosts making misogynist jokes or slut-shaming commentary about Lewinsky, one CNN commentator going so far as to call her a “young tramp” with no sense of irony.

You will find a similar montage in the seventh episode of Slow Burn, a new podcast from Slate’s Leon Neyfakh that also aims to deconstruct the Clinton affair, breaking down the complicated tabloid fervor of the late 1990s for contemporary listeners. While Lewinsky did not speak to Neyfakh for the show, the episode, “Bedfellows,” does much of the same work as The Clinton Affair. As it dissects the feminist response to the scandal and picks apart a particularly damning New York Observer roundtable in which several women writers defended the President, it notes just how poorly so many people, women included, treated the young Lewinsky at the height of her notoriety.

Between The Clinton Affair and Slow Burn, we are at a time of re-evaluating the culture wars of the 90s. By placing them in a historical context, we both examine and distance ourselves from events that are more recent than we’d like to think. This is an ongoing trend; in the last few years, popular entertainment has re-imagined and re-considered 90s headlines, from the OJ Simpson trial to the Tonya Harding incident to the Versace homicide to Princess Diana’s death. In each of these, it isn’t only figures like Monica Lewinsky who want to reshape and reclaim the narrative. These shows also give the audience a chance to do the same—to relive events and experience a more enlightened set of sympathies. New biopics and documentaries about this period are rarely surfacing new facts; they are presenting a way of feeling about the events and the lives caught up in them.

The Clinton Affair itself is not a perfect film. It drags at times, and at others feels too quickly paced. (Foster interviews Juanita Broaddrick at the end of the documentary, with only a few minutes to spare). But it finally presents Lewinsky in color. And perhaps, most importantly, it brings other women into frame. Foster gives nearly equal screen time to Lewinsky and to Paula Jones, the woman whose sexual harassment case against Clinton sparked the broader investigation into Clinton’s affairs (Clinton continues to deny her allegations). Lewinsky has endured impossible humiliations over the past twenty years, and it is moving to see her speaking up for herself with such eloquence and wisdom. But Jones, whose story also became a political cudgel (as recently as Trump’s campaign, when she sat in a press conference with him), has not had as many opportunities to reengage with the public. Jones’s tears throughout her interviews feel almost as searing and bruised as Lewinsky’s did sixteen years ago, when she was stumbling through the fog of fresh pain. While their stories are now landing on increasingly sensitive and engaged ears and achieving something close to televised vindication, it is clear, watching the two of these women relive the events that defined and eclipsed half their lives, that the hurt they endured cannot be undone.