Let’s say Washington is a swamp, as Trump calls it. Then lobbyists are the gators, and strong ethics rules are the fence that keeps Americans from getting bit. In President Donald Trump’s swamp, the gators keep getting bigger and the fence is in tatters.

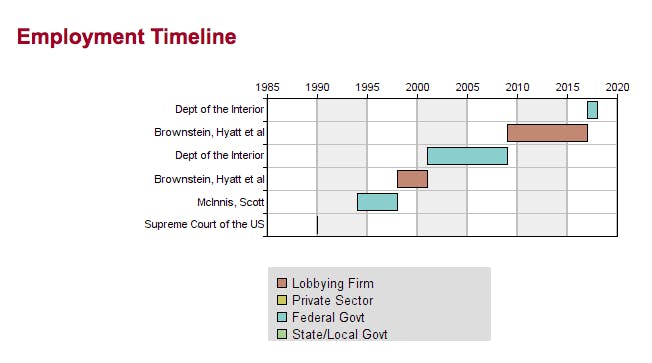

On Saturday, Ryan Zinke submitted his resignation as secretary of the Interior Department, the seventh-largest agency responsible for most of the nation’s natural resources and public lands. Zinke will be replaced—at least temporarily—by David Bernhardt, a former high-profile lobbyist for the fossil fuel industry and the Interior’s current second-in-command. As a lobbyist, Bernhardt worked on behalf of several oil companies that he’ll soon be in charge of regulating. He’s been called “a walking conflict of interest” by his critics.

Bernhardt’s ascent follows Trump’s announcement last month that a former lobbyist for the coal industry would soon be nominated to lead the Environmental Protection Agency. Andrew Wheeler has been serving as acting administrator since July, after former EPA chief Scott Pruitt resigned amid numerous ethical scandals. As a lobbyist, Wheeler represented Murray Energy—a coal company whose CEO literally sent Trump a wish list of all the environmental regulations he wanted dismantled. Trump’s EPA, now led by Wheeler, is on track toward fulfilling almost all those requests.

It’s alarming to know that two men who became rich by helping polluters dismantle environmental protections are about to lead the two most important federal agencies protecting public lands, wildlife, and human health. Many environmentalists believe that fossil fuel lobbying should disqualify Wheeler and Bernhardt from these positions.

But the mere presence of lobbyists in Trump’s cabinet doesn’t raise the alarm of government ethics experts. “The revolving door is a basic part of the Washington Establishment,” said Laura Peterson, an investigator at the Project on Government Oversight. “People go back and forth between the public and private sectors all the time.” It makes sense why they would; government agencies regularly deal with lobbyists when they’re crafting regulations, so they hire people who are familiar with the process.

The Trump administration does, however, seem “particularly comfortable stacking high-level posts with former lobbyists whose policy proposals are like a corporate Christmas list,” said Peterson. As ProPublica revealed in March, “At least 187 Trump political appointees have been federal lobbyists, and despite President Trump’s campaign pledge to ‘drain the swamp,’ many are now overseeing the industries they once lobbied on behalf of.”

These former lobbyists are not only flooding the government. They’re entering “a wild west environment where anything goes,” said Walter Shaub, the former head of the U.S. Office of Government Ethics from 2013 to 2017, when he resigned out of “disappointment” with Trump.

Shaub emphasized that previous administrations had “a lot” of industry members. “But past Republican presidents were similar to Democratic presidents in at least supporting the government ethics programs,” he said. President Barack Obama, for example, signed an executive order in 2009 prohibiting the government from hiring people who had been a lobbyist in the previous year. Special waivers could be granted, but had to be made public. A hired former lobbyist would also be prohibited from working on any issue on which they had previously lobbied.

Trump repealed Obama’s policy when he took office, replacing it with an executive order that he claimed would more effectively “drain the swamp.” But the ethics order has proven much weaker than Obama’s in practice, Shaub said. Now, lobbyists can be hired for any government position. Lobbyists can also work on issues where they have a direct conflict of interest, provided they get a waiver. And Trump has been giving these waivers out like candy to the most powerful people in his administration—at least 37 “to key administration officials at the White House and executive branch agencies,” according to a March report from the Associated Press.

But the total number of government officials with conflict-of-interest waivers is likely much more than 37, for two reasons: Trump’s ethics policy, unlike Obama’s, does not require waivers to be made public. His waivers are also often extremely vague, said Shaub, who now works for the nonprofit Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. “It’s impossible to count the number of people listed on a waiver, because they describe the type of person they’re waiving rather than directly naming them,” he said. The waivers granted to ex-lobbyists also “don’t offer any explanation” for why they’re needed.

This secrecy is perhaps the most troubling part of Trump’s lobbying policy. Of course, we want nothing more than to assume that government officials will act in good faith. But American history is littered with examples of those who were able to abuse their power thanks to a lack of transparency and oversight. The current administration is contributing more than its fair share to that ignominious list. Though he ran on a promise to “drain the swamp,” Trump is feeding with gators and letting them roam free—then asking us to trust him that the gators won’t bite.