The elderly Uncle Junior is in his armchair, facing down a disloyal male relation. In the next episode, Junior will get his hand stuck in the garbage disposal for six hours, but for now he has the dignity of a retired king, which is what he is. He holds up one hand, and says: “I’m in no shape for disharmony.”

After mainlining the entire Sopranos oeuvre this last week, Junior’s seated pronouncement is the moment that has stayed with me. Not the first time we see Tony take joy in strangling a man, not the violent death that takes Adriana away, not even the time Paulie Walnuts gets lost in the woods. No, I’m obsessed with the easy, elegant way in which The Sopranos’ patriarchs wield their power. With a word, peace is made or broken.

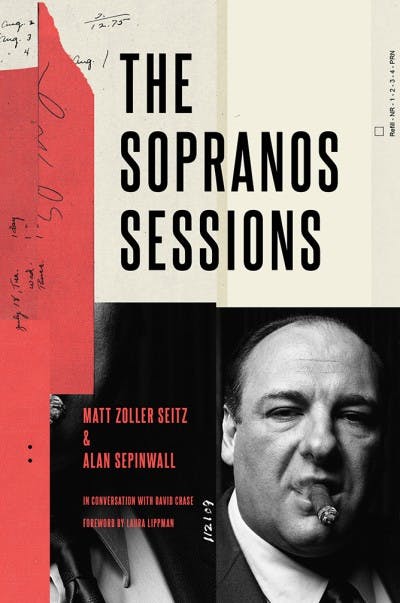

Today is the twentieth anniversary of the show’s first air date, and everybody is re-watching the series credited with inventing prestige television. Its creator David Chase is doing the media rounds, performing postmortems on that notorious final episode. And The Sopranos Sessions, a vast new book of critical essays covering every single one of the show’s 86 episodes, is newly on sale.

What is there even left to say? From the beginning, everybody knew that The Sopranos was to be a watershed. There would be before, and there would be after. In every commemorative article about the show, the author inevitably cites the list of prestige shows that followed The Sopranos and that adopted its central conceit of a flawed antihero—Breaking Bad, Mad Men, Deadwood, and so on. As Brett Martin argued in his 2013 book Difficult Men, an antihero who creates his own problems (Tony Soprano’s great insight is that he is his “own worst enemy”) in order to solve them introduces narrative stretches full of tension, action, fear, and glory. This is how the best television at the turn of the millennium was made.

But these are not the shows on television now. Instead, we’re in a weird new era in which everything on TV looks so good that you can’t tell whether it’s prestige or not. Call it post-prestige television. By this I mean that every show is cut beautifully, every soundtrack is great, and—crucially—every main character is rounded out by psychological flaws that make them seem human. From High Maintenance to Westworld, from Game of Thrones to Better Call Saul, television in the 2010s is a different and more sophisticated animal.

That is not to say that post-prestige TV is better than it was in the late 1990s. Watching The Sopranos in 2019, I was struck by how unpretty it is. The costuming is great and so are the sets—especially the hideous Soprano McMansion—but The Sopranos was not an especially artfully produced show. In between the great lines, we see hideous wigs and poor transitions. It’s not badly edited; it’s just badly edited by the standards of 2019.

The joy of The Sopranos lies in its script, so packed with symbolism and clever half-jokes, and the way that its cast executed that script. And therein lies the difference. Contemporary television is lusciously easy on the eye, always. But is the writing as good? Take The Haunting of Hill House, a gorgeously blue-toned investigation into a single family’s mental torture. Despite the glory of its source material in the Shirley Jackson novel, the show’s script was as anguished as its supposed themes. “A ghost can be a lot of things,” the family’s eldest son muses in episode one. “A memory, a daydream, a secret. Grief, anger, guilt. But, in my experience, most times they’re just what we want to see.”

Such writing is, frankly, dross. The best-scripted show of the past year is probably Killing Eve, Atlanta, or The Americans, but none of these quite match The Sopranos for its understated wit and its high-stakes investment in human relationships. So how did Hollywood end up learning the wrong lessons from The Sopranos?

Part of it stems from the way The Sopranos was received and defined by critics. In its early years, much commentary focused on the show’s brutal depiction of women, which in turn prompted defenses of its sophisticated portrayal of women complicit in evil. But it’s the male critics who have profited the most from the Sopranos-commentary boom—the men who were fascinated by the whole “flawed antihero” concept and pumped its meaning up to outsize levels.

Aside from a brief introduction by Laura Lippman, The Sopranos Sessions is written entirely by three men: Matt Zoller Seitz, Alan Sepinwall, and show creator David Chase. Similarly, if you click on the “critic reviews” section of The Sopranos’s page on Rotten Tomatoes, every single “top critic” listed is a man. The Sopranos Sessions is an excellent book, delving into all sorts of details and providing a rare opportunity to hear from Chase himself, who is shy of reporters. It even contains a “Eulogies” section, on the life and death of James Gandolfini, who played Tony and died at 51 in 2013. It’s an invaluable book to any fan, as was Martin’s Difficult Men and The Sopranos: A Family History (2001) by Allen Rucker. But when you put all those books together along with the general cultural debris surrounding the show, you get a very selective impression of what The Sopranos meant to Americans while it was airing—an impression dominated by antihero worship.

Of course, The Sopranos’s dissection of masculinity was innovative, even radical. But on the other hand, one might argue that The Sopranos simply did for television what Philip Roth did for fiction in the 1960s, and Martin Scorsese did for movies in the 1970s—made it human. And we do not remember the novels of Roth or the movies of Scorsese solely for their interest in the antihero. Instead, young writers and filmmakers look up to these men as pioneers of technique. The male psyche was rich material for Roth and John Updike and their peers, but those writers broke new ground because of the language they used to mine it.

There is plenty of great academic writing about The Sopranos, and much brilliant, unsung criticism. But the legacy of Sopranos-crit is of a genre almost exclusively manufactured by men, for a male readership, about the nerdy nitty-gritty of a TV show about masculinity. This has contributed, I think, to a new culture of television-making dominated by psychological portraiture, usually focused on men. It has also led to hyper-lush production, at the expense of scriptwriting, simply because it’s easier to throw money at a show than to write a good one.

This is the danger of allowing superfans to define the meaning of a television show. Though they may know The Sopranos better than anyone, they may end up taking away the wrong lessons. In the end, neither Paulie’s weird hair nor Tony’s panic attacks represent the core of what was good about The Sopranos. Instead, the show’s pedigree lies in its handling of a few words, here and there—an old man in an armchair denouncing “disharmony.” The joy of watching a Sopranos patriarch comes not only from his easy authority, but also from the language he uses to express it.

Despite the visual perfection of the shows being produced by Netflix and HBO today, the words have been lacking. That won’t change until we change the way we talk about the golden age of television in the 2000s. Without the script, there’s no Sopranos; without great writing, there’s no “prestige.” In the words of a certain TV gangster, after all, “What use is an unloaded gun?”