In his 1881 masterpiece, Epitaph of a Small Winner, the Brazilian novelist Machado de Assis instructs his readers to memorize the phrase “the voluptuousness of misery.” “Study it from time to time, and, if you do not succeed in understanding it, you may conclude that you have missed one of the most subtle emotions of which man is capable,” he warns. You will also have missed the key to Machado’s sly stories, which make for marvelous miseries.

On the face of it, Machado’s fiction is anything but miserable. The 76 pieces amassed in the newly (and deftly) translated Collected Stories are, for the most part, portraits of consummate comfort. Their denizens are the bourgeois inhabitants of fin-de-siècle Rio de Janeiro—doctors and lawyers who enjoy dependable incomes, employ domestic servants, and entertain vague plans to “enter politics,” not out of conviction but out of self-aggrandizing boredom. They occupy themselves chiefly with parties, post-prandial card games, and ill-advised affairs with their friends’ and associates’ wives. Like his American contemporary and closest literary relative, Henry James, Machado eschews physical descriptions and political commentary in favor of ornate social sketches. The translators of The Collected Stories, Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, observe that Machado regards Brazil’s cities and landscapes as an “outdoor drawing room.” When his characters dare to venture out of their tastefully furnished homes, they most often head toward Rua do Ouvidor, a boulevard lined with elegant shops.

The milieu

of the Collected Stories is dazzling,

but their author remains unimpressed. His high-society chronicles adopt the

formal yet familiar tones of an indulgent father toasting a spoiled child. And

despite his occasional surges of lyricism—in a story about a canon composing a

sermon, he remarks that words we forget are misplaced “in the immense attic of

the mind”—his voice is dusty with Latin locutions and dense with allusions to Schiller,

Montaigne, and Augustine. A reader could be forgiven for assuming that Machado

is a native of the ballrooms he describes with such facility.

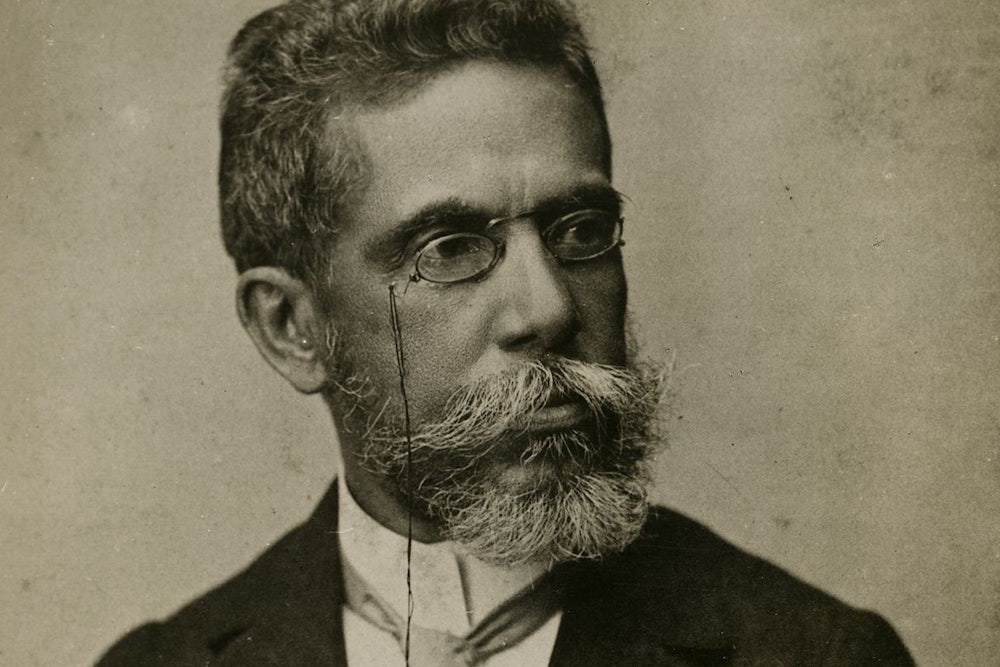

Yet Brazil’s most celebrated writer grew up in poverty and poor health. His father was a mulatto housepainter born to freed slaves. His mother, a white washerwoman, died of tuberculosis when he was ten, and he suffered from epilepsy, myopia, and debilitating headaches all his life. Slavery, the institution that had tyrannized his grandparents, was not abolished until 1888, when he was 49 years old. Despite (and to spite) his humble origins, he aspired to read the great works of world literature in their original languages, so he picked up French, Spanish, Italian, German, English, and, to some extent, ancient Greek. He translated Poe’s “Raven” into Portuguese and bequeathed a vast multi-lingual library to the Brazilian Academy of Letters when he died. Rumor has it that he learned French from a neighborhood baker and Latin from a sympathetic priest.

His first publication, a sonnet, appeared in Periódico dos Pobres (the Newspaper of the Poor) in 1854, when he was only 15. By the age of 17, he had secured a post as an apprentice typographer and proofreader at the Imprensa Nacional (the National Press). By 21, he was a well-established man of letters. When he died in 1908 at the age of 69, he left the world over 200 stories, more than 600 short newspaper columns (so-called “crônicas”), five poetry collections, nine plays, and nine novels. Largely thanks to three virtuosic exercises in modernist unrest—Epitaph of a Small Winner (1881), Philosopher or Dog? (1891), and Dom Casmurro (1899)—Machado de Assis is to Brazil as Pessoa is to Portugal and Goethe is to Germany.

Yet some of the Collected Stories, masterful works of shrewd sadism, rival even the Brazilian giant’s best-known novels. What begin as chatty anecdotes soon shade into something much darker. Even the apparent placidity of the early stories proves deceptive. Machado’s romances, too, are marked by a deviousness that is superficially playful but fundamentally ruthless. And what is more voluptuous than that?

Despite the refinement of its setting, Machado’s fiction inflicts unlikely tortures on its characters and cruel suspense on its readers. The interest of many of Machado’s early efforts is not their content—the letters exchanged, the hands hotly pressed, the women who vow never to marry, the men who persist in proposing—but of their viciously self-conscious artificiality. From the first, Machado courts belief and disbelief at once. “This is like a novel…I’m caught in the middle of a novel!” thinks the protagonist of the 1873, Novalis-inspired novella “The Blue Flower.” Yet nearly all of the collected stories contain deliberately documentary touches. Many, even those originally printed in the book Undated Stories, are set in specific years, and their author is always pleading that many of the crucial facts elude him. In “Much Heat, Little Light,” he regrets to inform the reader that he is not sure whether the protagonist’s love was reciprocated, since “history provides little information in this regard.”

“Miss Dollar,” the first of the Collected Stories, opens with a characteristically teasing flourish:

For the purposes of this story, it would be handy if the reader were kept waiting for a long time before finding out who Miss Dollar was. On the other hand, if there were no such introduction, the author would be obliged to make long digressions, which would fill up the pages, but without moving the action along at all. I have no alternative, therefore, but to introduce you to Miss Dollar now.

But Machado does nothing of the sort. Instead, he invites us to imagine “that Miss Dollar is a pale, slender Englishwoman” who subsists on “milky tea…along with a few sweets and biscuits to stave off hunger.” “All very poetic,” he concedes, “but nothing like the heroine of this story.” Next we are instructed to envision “a totally different Miss Dollar. This one will be a robust American girl” who “would prefer a decent lamb chop to a page of Longfellow.” “A more astute reader” might object that the heroine is sure to be “Brazilian through and through”—and this would, Machado laments, “be an excellent contribution if it were true; unfortunately, neither that nor any of the others is true.” In fact, Miss Dollar is an Italian greyhound—a proposition that, by dint of appearing in a fiction, is not strictly the truth either.

The point, I suspect, is not just to flaunt that a writer is free to fill his stories with conspicuous contradictions. Nor is it just to mock us for our own gullibility, which we demonstrate in good canine fashion as Machado trots out his series of false starts. It is also to show that a fiction is a fragile edifice, always subject to the revisionary whims of a capricious author. From the very first, Machado plants in his reader the subtle seeds of what will flower into full-fledged paranoia over the course of the ensuing 922 pages. He revokes so much of what he evokes that we learn to doubt almost everything he says.

Miss Dollar’s wide-eyed owner, to whom she is dutifully returned by the marriageable Dr. Mendonça, is too mistrustful to accept even a suitor she adores. Her aunt tells Mendonça, one of the thwarted hopefuls, “I believe in the sincerity of your love. I have for a long time, but how to convince a suspicious heart?”

How to convince a suspicious heart? This question animates the Collected Stories, which recycle and re-recycle the themes and fixations of Machado’s opus, Dom Casmurro. An elegy to anxiety, the novel follows Bento Santiago, a retired lawyer who suspects that his wife and his best friend are having an affair. His deranged memoirs are perfectly poised between the confirmation and allayment of his restless, relentless fears: They withhold the perverse relief of proof, languishing with what sometimes seems like pleasure in the agony of indeterminacy.

Though Machado’s own marriage lasted 35 years and was apparently happy, his sharply suspicious fiction makes us wonder. His favorite love triangles involve not just duplicity but the most brutal betrayals. Men who love their best friends’ wives or love interests recur in “The Blue Flower,” “Ernesto What’s-His-Name,” “The Fortune Teller,” “A Captain of Volunteers,” and “Pylades and Orestes.”

It’s only apt that the Collected Stories are so repetitive: The book is organized just like an obsession, with manic motifs that nag and gnaw. Its stories are crammed with jilted lovers, women with enticing arms and eyes, and scientists who torture mice. Almost all of them have intriguing beginnings and abrupt, twisted endings. One begins, “That young man standing over there on the corner of Rua Nova do Conde and Campo de Aclamaçao at ten o’clock at night is not a thief, he’s not even a philosopher.” Another begins:

So you really think that what happened to me in 1860 could be made into a story? Very well, but on the sole condition that nothing is published before my death. You’ll only have to wait a week at most, for I’m really not long for this world.

Nothing could—and nothing really does—live up to the implicit promise of openings so enigmatic. Yet the deprivations may be intentional: Lack, too, is voluptuous, and many of Machado’s characters willfully resist the satisfaction of their immense and obstinate appetites. In “Trio in A Minor,” a young woman torn between two underwhelming suitors hallucinates a voice proclaiming, “This is your punishment, O soul in search of perfection; your punishment is to swing back and forth, for all eternity, between two incomplete stars.”

In “A Sacristan’s Manuscript,” dreamy Eulália “began by idealizing things, and, if she did not end up denying them entirely, it is certain that her sense of reality grew thinner and thinner until it reached the fine transparency at which fabric becomes indistinguishable from air.” Determined to await the ideal husband, she remains unmarried for years. The eventual object of her affections is a priest: “She had clearly found the husband she was waiting for, but he turned out to be as impossible as the life she had dreamed of.” Meanwhile, the narrator, “both a gastronome and a psychologist,” continues to attend Sunday dinner at the house of the lonely woman. “If it is true, as Schiller would have it, that love and hunger rule the world, then I am of the firm opinion that something, either love or dinner, must still exist somewhere or other,” he concludes.

One of Machado’s characters, a miser who glimpses a friend’s coin collection, reflects, “The finest possessions are those we don’t possess.” It follows that we must cede what we have, at least if we hope to go on valuing it. Elizabeth Hardwick wrote in her incisive introduction to Dom Casmurro in 1991 that Machado’s heroes are apt to transform “a consummated love into the unattainable by way of jealousy.” Bento’s ecstatic distrust delivers his wife back over to beguiling inaccessibility, and Machado’s stories are full of comparable divestments. “The Gold Watch,” one of the best of the earlier stories, transfigures even the quelling of suspicions into suspicion-fodder. When Luis Negreiros finds a gold watch he does not recognize in his living room, he interrogates his wife, Clarinha, about its origins. She responds evasively, and he flies into a rage, grabs her “by the throat,” and threatens to kill her—only to realize that his birthday is the next day and that the watch is Clarinha’s present to him.

Though Clarinha’s name is cleared, it is not clear whether she will be able to forgive her husband for his violent outburst. The story ends on an unsettled note. The possessions we have don’t satisfy us, but the ones that elude us infuriate us. This is why even Machado’s most affluent characters remain, despite their expensive birthday presents, lavishly unfulfilled.

Misery is voluptuous not only for its victims but also for its architects. Machado’s first-person narratives are self-eviscerations: The narrator of Epitaph of a Small Winner writes posthumous memoirs from beyond the grave, and Bento likens his self-examination to an autopsy. Machado’s third-person works are sadistic experiments, full of physicians whose disinterested fascination with the sources of suffering often grades into active cruelty.

Many of them are testaments to their creator’s talent for devising monstrous ironies. In “The Holiday,” a child discharged early from school eagerly anticipates a surprise party, only to learn that his father has died. In “Posthumous Picture Gallery,” a man named Joaquim Fidélis, beloved by all for his exemplary warmth and kindness, dies unexpectedly. His nephew reads his journal and is appalled by his hidden malice. “I have referred to this friend many times and will do so yet again, provided he doesn’t kill me with boredom, a field in which I consider him a true professional,” he wrote of one close friend. Another has “the warmest heart in the world and a spotless character, but the qualities of his mind destroy all the others.” When the friends Fidélis has slandered ask to read his diary, the nephew turns them away. “What a difference from his uncle!” the friends chide. “What a gulf separates them! Puffed up by his inheritance, no doubt!”

The best story of all is also the coldest. In the haunting “Secret Cause,” Garcia, a kindly doctor, befriends Fortunato, a philanthropist and the benefactor of a hospital. It soon emerges that Fortunato’s interest in the misfortunes of others is anything but innocuous. One day, Garcia arrives early for a visit at his friend’s house and makes a horrifying discovery:

Fortunato was sitting at the table in the middle of the study, and on the table sat a dish of alcohol. The liquid was alight. Between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand he held a piece of string, from which the mouse dangled by its tail. In his right hand was a pair of scissors. At the precise moment Garcia entered the room, Fortunato snipped off one of the mouse’s legs; then he slowly lowered the poor creature into the flame, only briefly so as not to kill it, and then prepared to snip the third leg, for he had already cut off the first before Garcia arrived.

The description flails on and on, unable to die: “the miserable creature writhed and squealed in agony, bloodied and scorched…. Only the last leg remained; Fortunato cut it very slowly, his eyes fixed on the scissors.” When Fortunato’s wife, whom Garcia loves, dies, Fortunato watches Garcia as Garcia once watched him. Garcia, wracked with grief, sobs over the corpse of the departed, and “Fortunato quietly savored this outburst of spiritual pain, which went on, and on, for a deliciously long time.”

So, too, do we luxuriate in the pains and pangs of Machado’s battered characters, whose lingering trials twitch for so many pages. But Machado himself is the true beneficiary of all the opulent violence he conceives, records, and, finally, metes out to his fascinated readers. In “Among Saints,” the saints who step down from the walls of a church to pass judgment on the congregation “had penetrated into the lives and souls of the faithful and picked apart the feelings of each and every one, just as anatomists dissect a corpse.” They are possessed of “terrifying psychological insight.” Machado is himself a sinister saint. An author, he boasts, “can scrutinize every nook and cranny of the human heart.” As he picks not only his characters but also his readers apart, dangling us over the open flames, he can already see into our suspicious hearts: He already knows that we will spasm, not just with fear but with a rhapsodic rush of misery. The crowning cruelty is that we will enjoy it.