Last month, Media Matters surfaced a litany of racist,

misogynist, and creepy comments that Tucker Carlson made from 2006 to 2011 on shock

jock Bubba the Love Sponge’s radio show. Carlson’s attempts at dropping his

Brooks Brothers floor manager persona to sound like a regular joe are pure

cringe comedy. He passes off his now familiar white nationalism as comedy,

calling Iraqis “semiliterate primitive monkeys” and arguing that the Congressional

Black Caucus “exists to blame the white man for everything.” But in one call,

he throws even Bubba and his crew by defending child marriage, saying that cult

leader Warren Jeffs facilitating the marriage of a 16-year-old girl to an older

man “is not the same as pulling a stranger off the street and raping her.”

“Yeah, it’s—you know what it is?” one of Bubba’s co-hosts responds, genuinely

creeped out. “It’s much more planned out and plotted.” “That’s twisted!”

Bubba’s co-host shouts over Tucker’s stammering rationalizations. “That’s

demented!”

Carlson’s attempt at locker-rooming with the cool seniors only ended up clearing the locker room. Not long after the Media Matters story broke, many of the advertisers on Carlson’s highly-rated, if severely revenue-challenged, hour of Fox News prime time left, too. The irony is that when Carlson went on Bubba’s show to hang with the bad boys, it was to attract advertisers. In 2006, politicians and pundits regularly went on these shows to say edgy things or laugh at them, in a bid to appear less like the humorless stiffs they are, and expand their audience to a younger demographic.

Shock radio is a broadcast genre in which extreme, aggressive, explicit talk is meant to outrage the mainstream public while making the show’s devoted fans laugh. It took off nationally in the 1980s and ’90s, when the term “shock jock” applied interchangeably to a handful of radio personalities—Bubba, Don Imus, Rush Limbaugh, Howard Stern among them—who had distinct audiences and often loathed one another, but shared a taste for the wildly irreverent. Since then, however, the spirit of shock radio has come to animate the political language of modern times, transforming from fart jokes into today’s “triggering the libs” culture, which ranges from anti-Semitic 4Chan memes of concentration camp ovens to President Trump’s relentless trolling of Kim Jong-un, LeBron James, and pretty much everyone else. And no one has mastered that language like our troll-in-chief. How the merger of right-wing politics and dick-joke comedy came to pass is a story about Donald Trump, yes, but it has its roots in the late days of the Reagan administration.

While local shock jocks like Chicago’s Steve Dahl were already established in the 1970s, the shock jock era truly began in August 1987, when the Reagan Federal Communications Commission (FCC) made two changes that literally rewrote the rules of American media and comedy. First, it repealed the Fairness Doctrine, which required radio stations to balance controversial views with an opposing point of view. Rush Limbaugh was already the top-rated show at Sacramento’s KFBK and a veteran of “insult radio” when the doctrine was overturned, finally freeing him to do the show he wanted.

Limbaugh could now be as controversial as he liked without liberal pushback (or context, or fact-checking), and his now familiar menu of right-wing satire and conservative dogma quickly connected to likeminded listeners. Within a year, WABC brought him to New York to begin his national show. To break up his daily three hours of super-villain monologuing, Limbaugh introduced news about Ted Kennedy with a song called “The Philanderer,” a parody of Dion’s “The Wanderer.” And in an early example of a conservative mocking liberals as the real fascists, he began referring to feminists as “feminazis.”

The second, equally important 1987 FCC revision was to expand its power to fine shows for indecent material. In effect, the Reagan FCC stopped enforcing political debate in the media and chose instead to enforce its conservative morality. The FCC quickly became the young Howard Stern’s nemesis, fining his employers millions of dollars for his sexually explicit comedy, and making him the most government-harassed comedian since Lenny Bruce. Stern would get hired by a radio station, outrage local listeners (while drawing in new fans), risk a hefty fine or actually get the station fined, and then get fired. But in this new FCC-as-comedy-cop atmosphere, Stern made this triggering cycle work for him, as he moved up to better and bigger markets. As Stern once explained to David Letterman, “What’ll happen is some other radio station will hire me and pay me a lot of money to say obscene things, they’ll get uptight about it, and they’ll fire me.”

By 1988, Limbaugh and Stern were both syndicating shock from New York. At first glance, they looked like very different sides of America. Stern—a native of Queens, New York, and Jewish—came out of FM rock radio, grew his hair long, interviewed porn stars, trash-talked celebrities, laughed off prudes, and, for his millions of fans, offered an often devastatingly funny daily dose of lewd counter-culture to the conservatism of the Reagan and H.W. Bush eras.

Limbaugh grew up Methodist in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. A cigar-puffing, golfing, country-club culture warrior, he, too, trashed Hollywood and coastal elites, while deriding his liberal callers and critics and giving movement conservatives a voice. When Newt Gingrich won Congress back for the GOP in 1994 for the first time in 40 years, the incoming freshman class named Limbaugh an honorary member of the House, citing his show as motivating Republicans nationally to vote.

As they normalized and nationalized shock culture, the clashing styles of Stern and Limbaugh gave the impression that they represented two different political camps. As a 2003 Slate article argued, Stern and all his Morning Zoo imitators offered an answer to conservative talk radio, since they were “classic social liberals” who approached all issues, high and low, “unfailingly from a left-libertarian perspective”:

AM talk—Rush, Dr. Laura, Hannity—targets middle-aged white guys. Surprise: They tend to be conservative. But FM talk—Stern, Joyner, Mancow, Don and Mike in Washington, Tom Leykis in Los Angeles—scores with young men, guys who like their radio on the risqué side, with a bulging menu of sex jokes and a powerful message that this is America and you can do whatever you want. Hint to Democrats: You may not like to admit this, but these are your voters.

But in reality, Stern and Limbaugh had much more

in common culturally and politically. Both are white baby boomers:

Stern, 65, Limbaugh, 68. Both fostered a “bad boy” environment where they

played the alpha male to their decidedly

male fans, with Limbaugh declaring his show the

“EIB” or “Excellence in Broadcasting Network,” and Stern proclaiming himself

the “King of All Media.” While Limbaugh was decidedly in the conservative camp,

Stern was never left-leaning or even a true liberal. A centrist, he supported

Republicans like New York Governor George Pataki and Mayor Rudy

Giuliani, praised George W. Bush for invading Iraq and Afghanistan, briefly ran

for New York governor as a libertarian, and once swore off ever voting for

Democrats because of the FCC, whose indecency provisos he loathed as much as

conservatives hated the Fairness Doctrine.

As with trigger culture today, race-baiting comedy was a staple of both Stern and Limbaugh’s shows. Stern made KKK grand wizard Daniel Carver a member of his Wack Pack, the crew of oddballs whose lives Stern found hilarious and sad. While Stern mocked Carver, Carver had access to Stern’s millions of listeners for his quite serious attempts to recruit for the Klan, greeting them with, “Wake up, white people!” Besides Carver, Stern once played the song “N----- Claus” at Christmastime and often gave racist callers ample time to talk.

Limbaugh, too, trafficked in race-baiting humor. After Carol Moseley Braun became the first African American woman elected to the Senate, Limbaugh opened news segments about her with the theme song from The Jeffersons. One day, he asked in the tone of a Seinfeld-era stand-up comic, “Have you ever noticed how all composite pictures of wanted criminals resemble Jesse Jackson?” When Limbaugh claimed he could not understand what one African American caller was saying, he said, “Take the bone out of your nose and call me back.”

To deflect charges of racism, both Stern and Limbaugh employed African American sidekicks. In Stern’s case, that’s longtime broadcaster Robin Quivers. Limbaugh works alongside James Golden, aka Mr. Snerdley, his show’s call screener, producer, and engineer. During the Obama years, Limbaugh gave Golden airtime as the show’s chief Obama critic; Golden declared himself an “African-American-in-good-standing-and-certified-black-enough-to-criticize-Obama guy.”

Their presence lets the audience believe (if they care) that it’s all just jokes or the views of their racist guests, not the hosts. If Limbaugh or Stern were really racist, the thinking goes, would they hire African Americans? And if the shows were racist, would those African Americans be laughing, too?

When Stern and Limbaugh’s shows drew revenue-threatening backlash, they explained in their rare public apologies that it was all in jest. In 1995, after Stern mocked the murder of Mexican singing star Selena using a bad Hispanic accent over sounds of gunshots, the backlash stunned him. Scrambling, he attempted an apology in phonetic Spanish that’s as awkward as his original offense. It began with, “As you all know, I am a satirist ...” He went on to use the classic “it’s not me, it’s you” argument of claiming he was sorry if anyone was offended.

Limbaugh did the same in 2012 after attacking Sandra Fluke, a feminist activist who testified before Congress about federal funding for birth control. On his show, he repeatedly called her a “slut,” and ranted that if taxpayer money were to be spent on Fluke’s birth control, then taxpayers had the right to watch videos of her having sex. The viciousness aimed at Fluke appalled the general public, and, for once—most likely due to the graphic sexuality of the attack—his own culturally conservative audience. He, too, went for the “it’s satire” defense: “In the attempt to be humorous, I created a national stir. I sincerely apologize to Ms. Fluke for the insulting word choices,” he said, going on to describe what he does as answering “the absurd with absurdity.”

It might sound familiar. When Trump dealt with the fallout from the Access Hollywood tape, in which he was caught saying he had forced himself on women, he said he had been engaging in “locker room banter”—the type of comedic repartee between men that is the common currency of shock radio. “This was locker room banter, a private conversation that took place many years ago,” he explained. “Bill Clinton has said far worse to me on the golf course—not even close. I apologize if anyone was offended.”

It was a defiant, blaming non-apology, and it’s what Carlson issued after the Bubba the Love Sponge scandal. “Media Matters caught me saying something naughty on a radio show more than a decade ago,” he said in a statement. “Rather than express the usual ritual contrition, how about this: I’m on television every weeknight live for an hour. If you want to know what I think, you can watch. Anyone who wants to disagree with my views is welcome to come on and explain why.” None other than Donald Trump Jr. applauded Carlson for his refusal to apologize, saying, “This is how to handle the outrage mob.”

The real gap between Stern and Limbaugh’s audiences was age: Older dudes liked Limbaugh, younger ones, Stern. By 2006, when Carlson was calling in to Bubba’s show, the broadcaster who had truly united shock comedy with shock politics was Don Imus. In addition to a national radio show, his show Imus in the Morning was broadcast on MSNBC, where he appeared in a denim jacket, sunglasses (indoors), and cowboy hat, like a coked-up cattle baron who had spent the morning running Quakers off their farmland. A very successful early shock jock, he liked calling women and asking, “Are you naked?” As Stern and Limbaugh became his national rivals, Imus found a middle ground between them by inviting senior politicians and political reporters on the air to discuss the news, as Imus threw out informed questions and barbed comments.

In a 1993 New York Times profile, Imus counted as regular guests NBC’s Tim Russert; Senators Bill Bradley, Alfonse D’Amato, and Bob Dole; New York Mayors Dinkins and Giuliani; and Times columnist Anna Quindlen. Imus credited his multiple 1992 interviews with Bill Clinton with saving Clinton’s candidacy after Clinton was accused of having extramarital affairs. And the political world seemed to agree, revealing the depths to which both liberals and conservatives were enmeshed in shock radio culture. Senator John McCain, Brian Williams, Tom Brokaw, and Times columnists Frank Rich and David Brooks made up an A-list of political and journalism stars who also lined up to be on Imus’s show.

They also sat idly by or laughed along as Imus established himself as the most openly racist broadcaster in America. Imus reportedly referred to media reporter Howard Kurtz as a “boner-nosed ... beanie-wearing Jew boy.” William C. Rhoden, a black sports writer for The New York Times, was called “a quota hire.” Of Times White House reporter Gwen Ifill, Imus said, “They let the cleaning lady cover the White House.” Of Attorney General Janet Reno: “Ms. Reno, of course, has Parkinson’s disease, has a noticeable tremor. ... I don’t know how she gets that lipstick on looking like a rodeo clown.” According to Stern and Quivers, his bitter rivals, he had respectively referred to them as a “Jew bastard” and a “nigger.”

In 2007, Imus’s high-profile guests could not look away when he referred to the Rutgers womens basketball team as “nappy headed hos.” Like the Selena and Fluke incidents, publicly demeaning these women crossed a line. At first, Imus dismissed it as a joke, telling everyone to simmer down over “some idiot comment meant to be amusing.” Imus was fired, but eventually came back, hiring black stand-up comics Karith Foster and Tony Powell to be his Quivers and Snerdley. His career never fully recovered, and after five decades in radio, the Rutgers incident will most likely be in the first line of his obituary.

Today, Stern’s shock radio career is effectively over, as well. With a perch at Sirius, which is outside FCC broadcast regulations, and with an audience made up of subscribing fans, there’s no one left to trigger. Limbaugh’s influence has waned as well. In 2003, he lost a mainstream gig as a commentator on ESPN’s Sunday NFL Countdown when he offered up the opinion, apparently in all seriousness, that sports writers overrated quarterback Donovan McNabb because he is black. Subsequent controversies—Oxycontin addiction, fraud, the Fluke fiasco—further damaged his credibility. “Incredibly influential among conservatives,” The Washington Post’s David Weigel wrote of him in 2015, “but no longer shaping the culture.”

And what about their audiences? What happens when millions of establishment-suspicious, anti-P.C., politically ambivalent young men who like shockingly “honest” entertainers “who tell it like it is” grow older? You might just get a lot of Donald Trump voters. Trump’s base, as presented in the mainstream press, comes in various shapes and sizes. He’s a working class stiff from the Rust Belt who’s been left behind by the global economy. He’s a hick from the rural hinterland who is resentful of the cultural-political elites in New York, Washington, and Los Angeles. He’s a staunch social conservative who held his nose and voted for the morally compromised Trump to stick it to Hillary and the Democrats. He’s a one-percenter who wants a tax cut.

But the voter who likes shock radio—the voter who thinks Trump’s shock talk is a breath of fresh air in a stultifying political environment—well, that person is everywhere. Whether or not these voters agree with Trump on every issue, he speaks their language better than anyone else in modern politics. That voter defies type, geography, and class. The only things we can say with some certainty is that he is white and he is male.

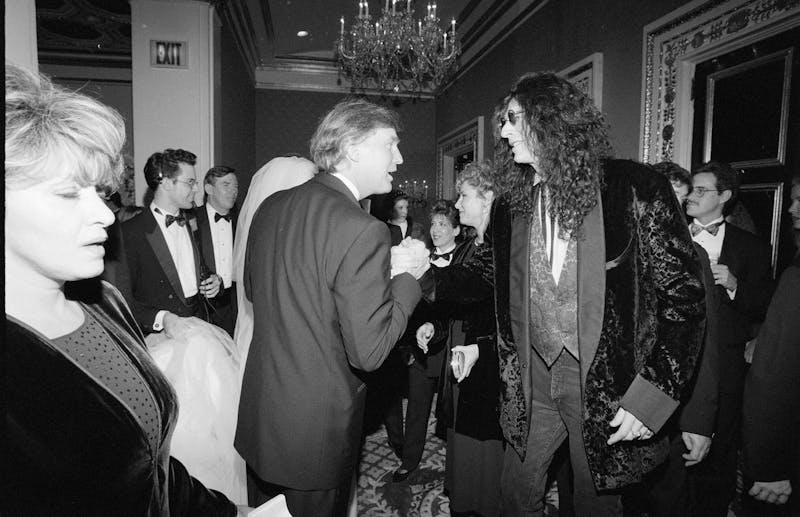

Shock’s legacy is baked into contemporary American politics, and if there is one person who threads the Stern-Limbaugh-Imus shock jock trifecta, it is obviously Trump. Trump was practically a member of Stern’s Wack Pack, revealing on-air that he finds his own daughter “very voluptuous.” On Imus, he mocked Native Americans when they posed a competitive threat to his casino business. And in this last phase of his life, as president of the United States, he gets support from Limbaugh. In explaining Trump’s appeal, Limbaugh could be talking about a fellow shock jock: “Understanding Trump’s easy ... He’s got an engaging personality. He doesn’t offend people. The left thinks he does, because they act offended. But Trump just makes people laugh.”

It’s been noted before that Trump learned his political attack style from shock, but he’s also the only one to successfully translate shock into social media, especially on Twitter, which in turn drives cable news and columns in national newspapers. On radio, it’s trash talk. Online, it’s shitposting, and say what you will, Trump’s troll game is solid gold. He has attacked any number of people for their race, gender, and disabilities, delighting his base and triggering the libs, with stunning success. Trump did not invent shock comedy, but there’s no one who has done it better or gained more from it.