In September of 1959, Nikita Khrushchev made his Hollywood debut. The Soviet premier had arrived in the United States for a twelve-day tour at the invitation of President Eisenhower. During his stay, Khrushchev visited a meatpacking plant in Des Moines where he tasted a hot dog (and by all appearances, loved it). In San Jose, he toured IBM, but was apparently more impressed by the cafeteria than the computers. The visit to Los Angeles was at Khrushchev’s request. His children wanted to see Disneyland.

But Khrushchev’s visit to Hollywood quickly went off script. Spyros Skouras, the president of Twentieth Century Fox, used the trip to advertise the studio’s upcoming musical Can-Can. The Soviet leader was taken to the set and posed for photos with Shirley MacLaine, who greeted him in Russian. A luncheon had been organized for the occasion, and all of Hollywood was desperate to get a peek at Khrushchev (though some, notably then-Screen Actors Guild president Ronald Reagan, declined the invite). In the waning years of the blacklist, a picture with a communist leader had all the allure of scandal without any actual repercussions. Elizabeth Taylor, Eddie Fisher (and Fisher’s ex-wife Debbie Reynolds) were all in attendance, as were Zsa Zsa Gábor, Frank Sinatra, and most importantly—Marilyn Monroe. Monroe, who at first was reluctant to come, changed her mind when the studio bosses told her that in Soviet Russia, America meant two things: “Coca-Cola and Marilyn Monroe.”

Khrushchev tolerated the media circus, but a last-minute change to his itinerary brought out his famous temper. When he went up to the podium to address the glitzy audience, he was furious. He had just been told that the trip to Disneyland was called off for safety reasons. His disappointment was visceral. “Is there an epidemic of cholera there or something?” he fumed, angrily gesticulating as the biggest movie stars on earth looked on, awkwardly, afraid he’d threaten to bury them again.

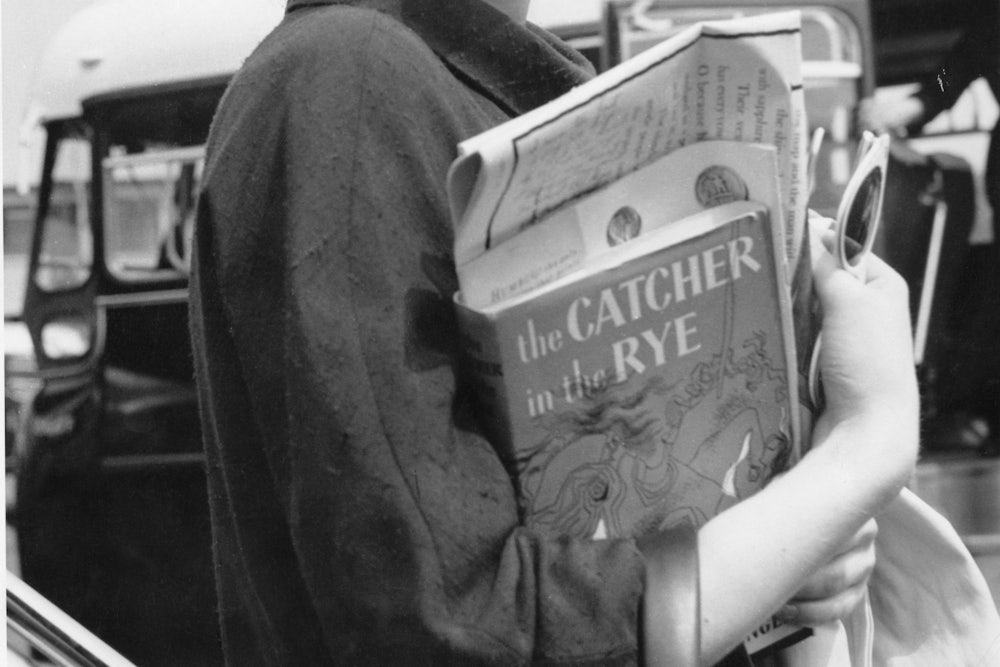

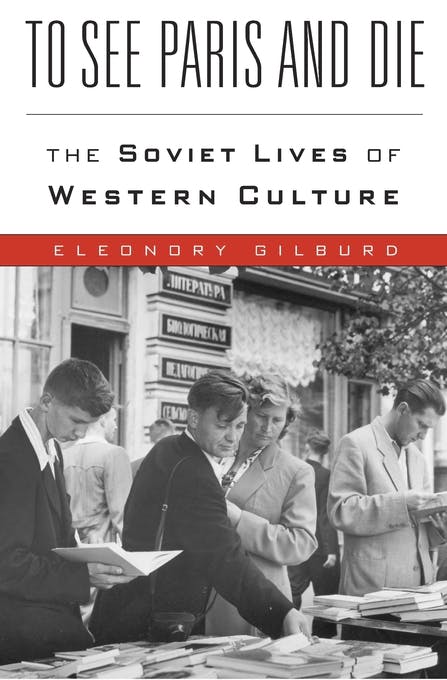

I thought of this anecdote, and Khrushchev’s giddy, almost childlike delight at the prospect of seeing Mickey Mouse when reading To See Paris and Die: The Soviet Lives of Western Culture by historian Eleonory Gilburd. Gilburd’s book focuses on a period in Soviet history known as “the Thaw” or “Khrushchev’s Thaw,” when censorship in the Soviet Union relaxed and Cold War tensions abroad started to ease. The term gets its name from Ilya Ehrenburg’s 1954 novel The Thaw, which broke with the tenets of Socialist Realism (the country’s official artistic policy) and openly condemned Stalin’s Purges. Khrushchev’s policy of “peaceful cooperation” with foreign powers also meant a sudden and large-scale influx of Western art, from Italian neorealist films to J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, into the Soviet Union.

To See Paris and Die tells us what happened to those Western books, films, and paintings behind the Iron Curtain—how they took on new, sometimes unexpected interpretations. For young people, she argues, reading foreign literature wasn’t necessarily about aligning themselves with the West, but was part of defining themselves as a post-Stalin generation, who belonged to a new, more open era. In this sense, To See Paris and Die is, at its core, a well-researched historical study of the process of distortion. By tracing the Soviet afterlives of Western art, Gilburd gestures toward a larger narrative, one that lays bare the processes by which we create myths about other parts of the world in order to understand our place within it.

Like Khrushchev, who was at once fascinated by America and suspicious of it, Soviet audiences met Western art with a complex array of emotions, attachments, and fears, a potent brew that still characterizes much of Russia’s sentiments (and resentments) toward the West today. As Gilburd reminds us, the Thaw Era impulse to measure progress by one’s engagement (or lack thereof) with the West came from a longstanding tradition in Russia, going back to the era of Peter the Great, the country’s great Westernizer who forged a European capital in his name, Saint Petersburg (his “window to the west”). “Both in Imperial and Soviet societies,” Gilburd writes, “the West had been alternatively a tool for self-examination, an exemplar, or a bogeyman.”

In the nineteenth century, a great debate ensued between “Slavophiles” who believed Russia’s path forward lay in embracing all that made it uniquely Slavic (mostly Orthodoxy) and “Westernizers” who wanted Russia to adopt Western ideals (mostly liberalism). Gilburd reminds us that these debates largely hinged on a view of Western Europe that was fictitious. According to the nineteenth-century philosopher Georgy Fedotov, “a unified Europe had more reality on the banks of the Neva or the Moscow river than on the banks of the Seine.” The imagined freedoms and unfreedoms of the West have historically served as distorted mirrors through which Russia viewed itself. Likewise, the interpretation of Western art, literature, and philosophy was often a practice of self-making. In Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky used his protagonist’s descent into immorality, fueled by his consumption of Western books, to praise the virtues of Russian Orthodoxy.

Under Stalin, nationalism in art, literature, and film became part and parcel of the Soviet project. He railed against “rootless cosmopolitanism,” an anti-Semitic dog whistle meant both to question the patriotism of Soviet Jews and to draw an equivalence between reading foreign literature and colluding with foreign governments. Many popular works of Western literature went out of print (though Stalin continued to enjoy the films of John Wayne in his private study). For the Russians that Gilburd writes about in To See Paris and Die, the West was more a signifier than a place; in watching the films of Fellini and reading the novels of Remarque, Soviet citizens were demonstrating their newfound freedoms.

The reading culture that sprang up around the works of Ernest Hemingway perhaps exemplified this best. Hemingway’s most famous novels, A Farewell to Arms, The Sun Also Rises, and For Whom the Bell Tolls had actually been available in the Soviet Union as early as the 1930s, but “it was during the thaw,” Gilburd explains, “that people singled out reading, and importantly, talking about Hemingway as a defining generational experience.” The Russian translation of For Whom the Bell Tolls, which Gilburd describes as “the literary smash of the 1960s,” was recast as a defiant symbol against the repressive 1930s. Reading the novel, which raised questions about the ethics of killing, even for a leftist cause like the Spanish Civil War (which had been much romanticized in the Soviet Union), became a way of signaling one’s intellectual freedom and independence of thought. What made For Whom the Bell Tolls especially appealing to this new generation was that Hemingway was openly critical of certain communists without disavowing communism.

Soviet readers desperate to get their hands on Western literature during the Thaw were not anti-communist. Indeed, J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye was beloved by Soviet critics and readers alike, who saw in Holden Caulfield’s contempt for a world of “phonies” an indictment of American culture “where everything was for sale.” For Soviet audiences, imbibing Western culture, and in fact, misinterpreting it, was an expression of a freedom, particularly after the Stalinist era where works of art were to be interpreted as the Party dictated.

This is why, Gilburd explains, French impressionism took on incredible significance during the Thaw. In 1958, Ehrenburg published an essay called the “The Impressionists” in which he tried to rehabilitate the French artists whose work had been deemed confusing and thus bourgeois. The impressionist dictum that vision was “entirely subjective” symbolized a kind of independence from the strictures of Socialist Realism, which mandated that art have one, clear, partisan meaning. Impressionism, Gilburd tells us, “allowed for a multiplicity of meanings” in a new era where “faith in encyclopedic authorities, unambiguous answers and correct interpretations was on the wane.”

The Thaw, like any official state policy, was of course strategic. Just as the CIA sponsored leftist magazines and abstract expressionism to assert American cultural supremacy (and to make censorship seem like something that only happened in communist countries), the Thaw mobilized the availability of Western art to combat the image of the Soviet Union as a repressive regime. Cultural exchange programs and film industry trade agreements were part and parcel of this. The Soviets, Gilburd explains, wanted people in the West to see their achievements in cinema, not merely to “propagandize revolution” but to “claim Soviet cinematic ascendancy.”

Integral to that mission was the creation of the Moscow Film Festival in 1959. Buoyed by the success of the Soviet film The Cranes Are Flying, which took home the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film festival in 1957, the Soviet cultural establishment was anxious for the world to see the art that communist countries were capable of producing. The Moscow Film Festival, which still runs today, was intended to be like Cannes “without beaches” and other bourgeois trappings. Indeed, warmer coastal cities like Sochi and Yalta were rejected as venues for the festival because, as Gilburd puts it, “both offered too many opportunities for undressing.” In its heyday, the festival attracted superstars like Elizabeth Taylor and Sophia Loren; the latter won an award for her role in Marriage, Italian Style.

To See Paris and Die offers a glimpse into a side of the Soviet Union that’s often given short shrift in our cultural memory: its incredibly international orientation. Despite largely closed borders, the Soviet Union invited, from its earliest days, visitors from across the world. In the 1920s and 30s, the country became a beacon for travelers looking for lessons in how to build a more just and equal world. When the leftist poet Langston Hughes was making arrangements to sail to the Soviet Union in 1932, he sent a telegram saying, “Hold that boat, cause it’s an ark to me.” The Thaw of course represented a different kind of international engagement than the 1930s; this time, American visitors weren’t coming with stories of the Great Depression and interwar austerity, but with washing machines and other suburban comforts.

To See Paris and Die looks at how, despite these temptations, encounters with foreign art and other objects were not conduits to defection, but supplied a reason to recommit to the Soviet project. In the Soviet Union, Gilburd’s book reveals, Western art was essentially unrelated to the West itself. Rather, it was a prism for debates about subjectivity, freedom of expression, and identities beyond the nation. In that way, To See Paris and Die gestures more broadly at what we do when we interpret the foreign. Are we truly learning about other people, other modes of being, or are we merely looking for new ways to imagine ourselves? In the Soviet Union during the Thaw, it was certainly something closer to the latter, but in a way that feels worth celebrating. Western art was freely appropriated and misinterpreted by Soviet audiences, but that was the point: They were free.