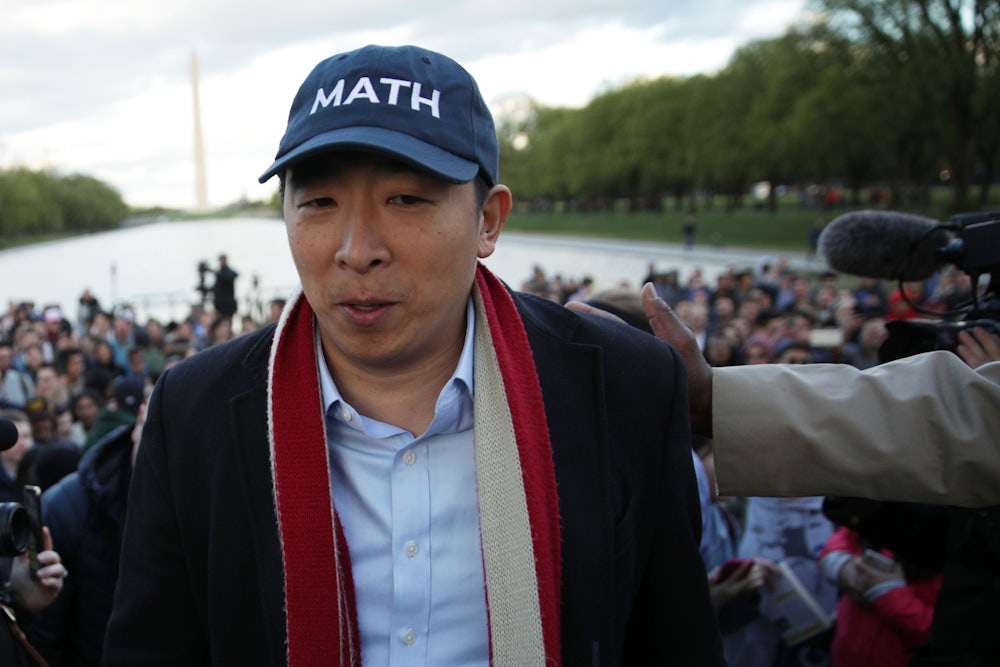

There are more than 20 Democratic candidates for president, and none are as technocratic as Andrew Yang. The New York–based entrepreneur and venture capitalist is running on an eclectic platform that synthesizes ideas from the party’s socialist and centrist wings. Though he’s never held elective office, he’s secured an enthusiastic following known as the “Yang Gang” and now polls in the low single digits—no small feat in this crowded field.

On the campaign trail, Yang outlines his policy agenda in three pillars: a universal basic income of $1,000 per month, Medicare for All, and what he describes as “human-centered capitalism.” Beyond that, he’s put forward a heterodox mix of more than 100 policies on his candidate website. Most of them, like paid family leave and the DREAM Act, are relatively standard Democratic fare. Others, like regulating artificial intelligence and transitioning to self-driving vehicles, reflect his futurist approach to governance.

Like many Democrats, Yang devotes no small amount of attention to structural reforms of the American political system. Many of his proposals are worthwhile. He supports automatic voter registration, statehood for Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, and ending felony disenfranchisement and partisan gerrymandering. But some of his more unorthodox ideas would be more complicated to enact than they first appear—which says more about the nation’s contorted political system than about Yang’s solutions for them.

Perhaps his most unusual proposal pertains to the Electoral College. Most Democratic candidates now support abolishing it, and for good reason: Only three of the five Democrats who won the national popular vote over the past three decades won the presidency. But Yang is skeptical of abolition. “Constant calls to change the electoral college after a popular vote win/electoral college loss can seem like sour grapes, and the attempt to abolish it would require a constitutional amendment that could be stopped by 13 states,” he argues on his website.

Yang instead calls for the states to allocate delegates on a proportional basis, like Maine already does. But there would be nothing to stop state legislatures from switching back for short-term advantage whenever it suited them. A hypothetical Democratic candidate could secure a narrow nationwide majority in November 2020, only to see Republican lawmakers in Texas or Florida reimpose a winner-take-all system before the electors gather to cast their votes in December. (Democrats in California and New York could do the same to a hypothetical Republican victor, too.)

This isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. In recent years, a few GOP state lawmakers have floated proposals to allocate their states’ electors by congressional districts that also happened to be gerrymandered in their favor. Yang also proposes making this proportional Electoral College system mandatory through a constitutional amendment, which would solve the gamesmanship problem. But it raises new questions: Why, for example, should the Electoral College’s opponents settle for a half-measure that entrenches a flawed system instead of marshaling their energy to scrap the system entirely?

Yang’s proposal to lower the voting age to 16 years old would also face complications. The current minimum age of 18 years old is established by the Twenty-Sixth Amendment. Yang grounds his case for the change in social science: Voters who cast their first ballot when they’re young are more likely to vote again in the future. “At 16, Americans don’t have hourly limits imposed on their work, and they pay taxes,” he argues. “Their livelihoods are directly impacted by legislation, and they should therefore be allowed to vote for their representatives.”

To change this, Yang calls on Congress to set the voting age to 16 years old in federal elections. That’s well within Congress’ power to do. The problem is that federal lawmakers can’t force states to lower their voting ages in state and local elections. When Congress in 1970 reauthorized the Voting Rights Act of 1965, it included a provision that lowered the voting age to 18 years old nationwide. Later that year, the Supreme Court ruled in Oregon v. Mitchell that Congress lacked the power to order states to lower their voting ages for state and local elections. Faced with the prospect of maintaining two separate voter rolls and ballots, the states quickly adopted the Twenty-Sixth Amendment the next year.

An act of Congress that reduces the federal voting age to 16 years old may not have the same compulsory effect today as it did in 1970. Lawmakers in Republican-led states have a strong incentive to keep young voters from participating. Sixty-seven percent of voters under 30 in last year’s midterms cast their ballots for Democratic candidates, which helped the party retake the House of Representatives. Fifty years ago, those lawmakers might have opted to harmonize their voter ages to avoid the onerous costs of running two voting systems instead of one. In today’s zero-sum climate, however, they might find it to be a sound investment in their own political futures.

Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and other Democratic candidates have also put forward proposals for how they’d reshape the architecture of American democracy. Unlike them, Yang doesn’t weave his preferences into a holistic vision for how American power structures should operate. His platform instead resembles a menu of options for the electorate to pick and choose from. That gives him a certain degree of political flexibility and lets him jettison trickier ideas more easily if he wins. But it also means he doesn’t have a rallying cry as energizing as Warren’s war on corruption or Sanders’s crusade against inequality.

This doesn’t mean Yang is wrong. Technocrats often face the challenge of enacting their policy vision in a political structure designed to resist it. Even when Yang proposes questionable answers to genuine problems, those answers do a good job of highlighting the flaws worth fixing. It’s also no real criticism to note that his ideas aren’t workable within the current system. If anything, it reflects how the American political system currently works to hinder democratic participation rather than encourage it.