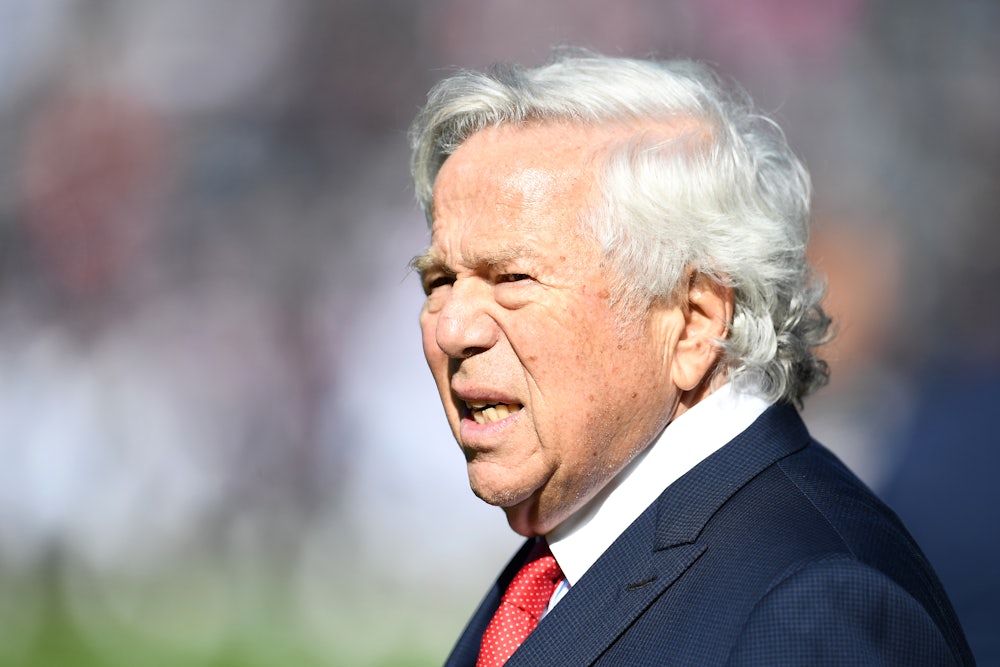

Before February, Robert Kraft was mostly known for two things: winning six Super Bowl rings as owner of the New England Patriots, and losing one of them to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Then Florida prosecutors charged the 77-year-old with soliciting prostitution after secretly videotaping his encounters with masseuses at a day spa in Jupiter, Florida. Kraft and hundreds of other men had been ensnared in an investigation into what police described as a multi-million-dollar sex-trafficking operation.

Kraft could have pleaded guilty, paid a fine, and put this episode behind him as quickly as possible. Instead, he refused a plea deal and waged an all-out war against the charges. And on Monday, the NFL tycoon won a major legal victory in his case after a judge ruled that the video evidence couldn’t be used at trial because police had illegally obtained it with a “seriously flawed” warrant. If it stands, the ruling makes it far more likely that Kraft will successfully get the charges thrown out without a trial.

Kraft’s brush with the American criminal justice system is atypical, to say the least. That makes it all the more instructive. His case punctured some of the overheated rhetoric surrounding coerced sex work and highlighted the power dynamics that police and prosecutors often enjoy over defendants—not because it worked against him, but because it didn’t.

The initial charges against Kraft came as part of a sweeping, dramatic raid on Asian massage parlors across Florida. State and federal law-enforcement agencies spent eight months building their case, eventually bringing charges against more than 300 men and the owners of almost a dozen parlors. Kraft was one of 25 men charged with misdemeanor solicitation to commit prostitution for acts that allegedly took place inside Orchids of Asia Day Spa in Jupiter. The Patriots owner pleaded not guilty to the two counts against him in February and issued a public apology for having “hurt and disappointed my family.”

Local prosecutors told the public they had smashed a international sex-trafficking ring and caught some of the country’s most privileged citizens participating in it. (Another Boston billionaire, John Childs, was also charged in the case.) “The men are the monsters in this case,” Marin County Sheriff William Snyder told reporters in February. At a press conference shortly after the raids, Palm Beach County State Attorney Dave Aronberg suggested that the defendants might face additional charges for their connections to it. “Human trafficking is the business of stealing someone’s freedom for profit,” he warned. “It can happen anywhere, including the peaceful community of Jupiter, Florida.”

The narrative changed just as the public’s attention turned elsewhere. Reason’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown noted the following week that Florida officials walked back many of their most inflammatory claims, including the allegation that the parlors engaged in human trafficking. “We have no evidence that there’s human trafficking involved,” a state prosecutor told a judge during a hearing in April. This is an all too familiar refrain. While sex trafficking can be a legitimate problem, law enforcement agencies also often use it to describe and justify crackdowns on consensual sex work.

To build a case against Kraft and the other defendants, police obtained what’s known as a “sneak and peek” warrant to place cameras inside the day spa, telling a judge that they suspected human trafficking was occurring behind closed doors. According to Kraft’s lawyers, police officers created a fake bomb threat against the day spa to evacuate it so they could slip in and install cameras in the private massage rooms. From there, they reportedly amassed a trove of footage of masseuses providing a range of sexual services to some customers.

That’s not all they filmed, though. Police are supposed to stop recording when they aren’t witnessing criminal activity, a process known as minimization. The warrant didn’t provide the proper instructions for officers to avoid violating people’s Fourth Amendment rights, Judge Leonard Hanser wrote in his ruling on Monday. As a result, the government filmed innocent patrons of the day spa in intensely private situations for no legitimate reason. “The court finds that the search warrant does not contain required minimization guidelines, and that minimization techniques employed in this case did not satisfy constitutional requirements,” he concluded. His ruling means the footage can’t be used in a trial.

Kraft’s lawyers could file a motion to dismiss the case as soon as this week. If Kraft succeeds, it will be because he had advantages that other defendants did not. His wealth and connections provided him with the best available legal representation, as his lawyers flooded the court with motions to throw out the likely embarrassing tapes and keep them sealed from the press and public. In an ideal world, every American would have access to the same level of legal defense that Kraft does. But many can’t afford any lawyer, let alone some of the best in the field, and they suffer for it. Florida’s public defenders, for example, are saddled with 200 to 400 felony cases each year and paid less than almost any other government attorney.

As they did in this case, prosecutors regularly use the threat of additional charges and a prolonged trial to induce defendants to accept a guilty plea. Time and resource constraints make those deals an attractive proposition not only to the defendants, but to judges and public defenders. This warps the criminal justice system, such that courtroom drama in the vein of Law & Order is becoming a thing of the past: Between 90 and 95 percent of federal and state cases are now resolved through plea deals instead of a trial with one’s peers.

In the age of mass incarceration, it’s natural to think that the United States has the harshest, most punitive criminal justice system in the free world. That doesn’t tell the whole story, though. For some Americans, it’s relatively easy to vindicate themselves in a court of law—to quash bad warrants and suppress bad evidence, to thwart overzealous prosecutors and defeat spurious charges before they even reach a jury. The only question is whether you can afford it.