Revolutionaries have long wanted to abolish the family. Marx didn’t see it surviving the eradication of capitalism. The radical feminist Shulamith Firestone viewed it as the root of all gendered oppression, imagining in her 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex a world of test-tube babies and (less well-remembered) chosen families, entered and dissolved at will.

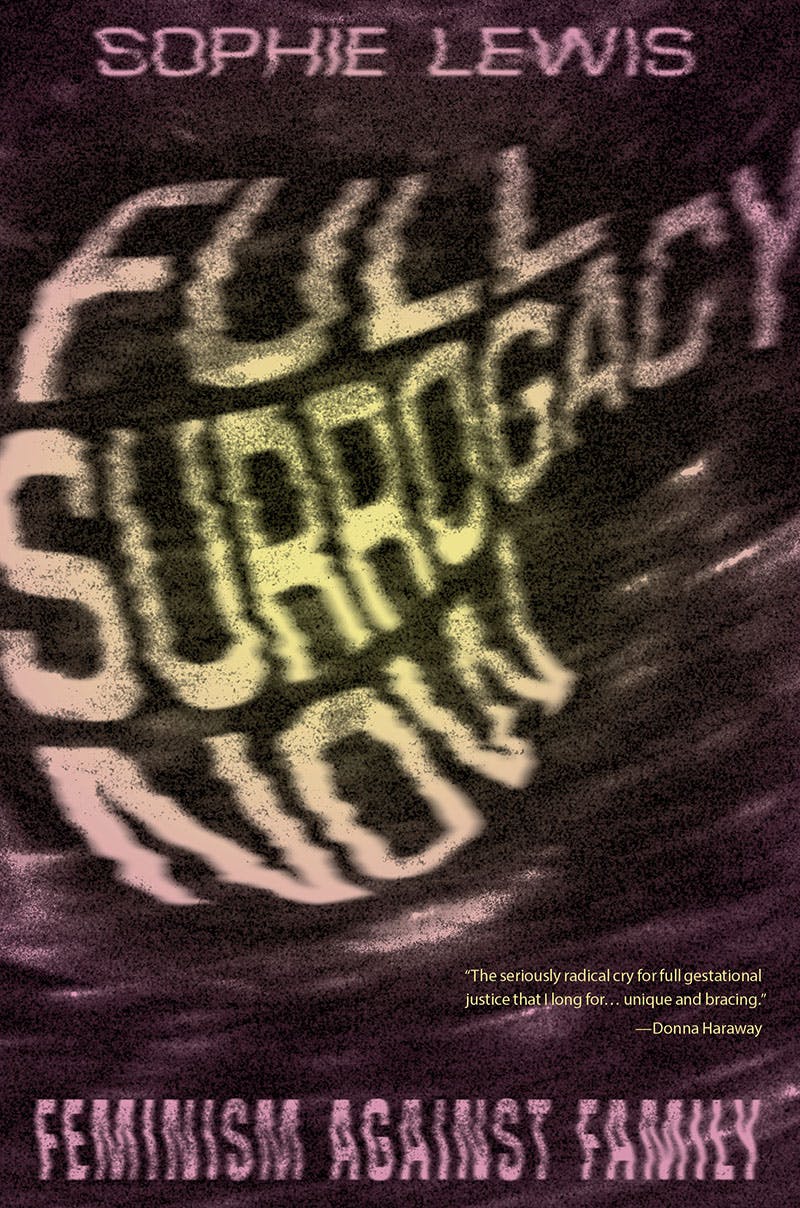

In a new book, Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family, queer feminist theorist and geographer Sophie Lewis revives such calls. Though the family is where most people seek solace from the world as we know it, she argues that it also upholds the forces that send us in search of relief. Like Marx and Engels, she posits that the family fuels capitalism by inducting successive generations into hierarchy, and like Firestone, she accuses it of inculcating gender inequality. Most pointedly, she argues that the institution turns our most intimate relationships into commodities, framing children as something like property: private investments in the future that belong only to the people who made them.

To dismantle capitalism, Lewis argues that we need “gestational communism”—a world in which babies are “universally thought of as anybody and everybody’s responsibility, ‘belonging’ to nobody,” and in which baby-making is “distributed and made to realize collective needs and desires.” In such a future, biological kinship would be replaced by devotion to “kith and kind,” and we would finally see that we are all responsible for one another.

Making this case for a family-free utopia today is far from easy. In the Trump era, surrogacy has become a kind of symbol for patriarchal oppression. After the election, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale surged up best-seller lists to become the most-read book of 2017, according to Amazon data. In the novel, Christian fundamentalist oligarchs have taken over America and forced fertile women to act as surrogates, by raping them and compelling them to bear their children. For a new generation of readers, the requisition of the handmaids’ wombs quickly came to represent attacks on women’s agency writ large, particularly in attempts to restrict abortion access. For the pro-choice protestors who storm state capitals dressed in red handmaid habits, the concept of surrogacy has come to stand in for all this unfreedom.

If surrogacy seems inherently dystopian, Lewis argues, it’s because we haven’t tried to imagine a world in which surrogates give their services freely, from a position of equality. Today’s surrogacy industry promotes the idea that surrogates are not real workers, but poor women who have few other options. Lewis examines how Dr. Nayna Patel, the mediagenic founder of the celebrated Akanksha Infertility Clinic in Anand, India, frames surrogacy as a route out of poverty for unskilled women, a jobs program where they busy their hands learning “embroidery, machine-sewing, computing, candle-craft, and beauty treatments” while they wait for the leases on their uteruses to run out.

When, in a documentary about Akanksha, a recruiter complains that Patel doesn’t pay enough, the clinician “tacitly justifies her denial of wage increases by framing surrogates as idle poor only transitioning into dignified work,” Lewis writes. Under this logic, “Surrogacy isn’t a job after all but a win-win investment, not so much a source of wealth as an internship.” (Lewis doesn’t say how widespread such attitudes are. Much of her critique of the surrogacy industry is based on her study of this single clinic—a choice that occasionally feels limiting.)

At the same time, Patel romanticizes her services to the advancement of her own ends. In one interview, she told the BBC that Indian surrogates act out of pity for childless couples, conjuring, Lewis writes, “a proletarian who is not particular about her fee” and “a volunteer so angelic and so compassionate” that she will “do anything” to give the gift of life.

If we saw gestation as work, on the other hand, we could imagine surrogates bargaining or going on strike. Lewis quotes a PBS segment about a surrogate who, barred from traveling to see a dying family member, threatened “to ‘drop’ the baby”—in other words, to abort a healthy pregnancy—if she wasn’t allowed to go. Another woman protested her confinement by escaping the clinic and threatening to keep the baby she bore. These tactics are not available to everyone; in many countries that allow commercial surrogacy, such as Kenya and Nigeria, most abortions are illegal and therefore unsafe, and ending up with an unwanted child is too high a price to pay for an act of resistance. Still, Lewis reasons that for surrogacy to shed all traces of the Handmaid’s Tale, it must be founded on a right to bodily autonomy, including the right to stop being a surrogate. If surrogacy is work, then workers can quit—a situation that confers real power.

Lewis hopes that in the future empowered surrogates might “come knocking” on the doors of the households they helped create, demanding a degree of acknowledgement that could undercut the illusion of the self-contained family, effecting a reminder of our inescapable entanglement. As it stands, many commissioning parents choose not to stay in touch with their surrogates, and some change their minds after agreeing to do so. Every family photo of a mother and father holding their baby with no surrogate in sight—every image from which the surrogate has been excised, Lewis writes, like an “unsightly prosthesis”—reinforces the idea that the nuclear family is natural, and has no alternatives.

Lewis imagines that one step on the road to “gestational communism” might be a form of surrogacy that instead forges lasting bonds between affluent buyers and the residents of the global south from whom they seek services. (In a world of “full surrogacy,” she says, surrogacy would not be performed for profit.) On a molecular level, she argues that the industry already binds people together more than most want to acknowledge. “There is a simple but infrequently noted kind of beauty to the fact that the gestating body does not necessarily distinguish between an embryo containing some of its own DNA and an embryo containing none,” Lewis writes. “There may be radical, chaotic consequences to exposing the falseness of the surrogacy industry’s guarantee that a buyer’s baby will not emerge to greet them full of somebody else’s blood and guts.”

Here, ultimately, is the utopian potential that Lewis sees in surrogacy: It reminds us that procreation is never truly reproduction, and there is no such thing as one’s own child. In the womb, gestation affects gene expression in ways we’re still discovering. Outside it, even the products of the most normative families bear the imprints of aunts, uncles, teachers—a whole network of other people. “We are the makers of one another,” Lewis writes. “And we could learn collectively to act like it. It is those truths that I wish to call real surrogacy, full surrogacy.”

What, then, would a world of “full surrogacy” look like? Lewis’s utopian vision is distinctly decentralized: Gestators wouldn’t be “surrogates” in that they bore children to be raised by the state, but rather in that they would create children who chose their own kin. Among the most concrete models Lewis cites is Firestone’s Dialectic, which imagined communist “households” of “ten or so consenting adults” who would share domestic labor and the care of their biological children or children they adopted together. At any time, children and adults alike would have the right to “transfer out” of the household and into another (a right Firestone suggested the state might have a role in enforcing, much as it currently regulates marriage and divorce). The goal, she wrote, was the “weakening and severance of blood ties” until all relationships between adults and children would be formed on the basis of natural affinity instead of need or obligation:

Adult/child relationships would develop just as do the best relationships today: some adults might prefer certain children over others, just as some children might prefer certain adults over others—these might become lifelong attachments.

Firestone is best remembered for proposing that all reproduction be automated—a shortcut to the “severance of blood ties” that struck many as intolerably Brave New World. Unlike her predecessor, Lewis doesn’t believe that the “techno-fix” of automation will be the means by which we alter human behavior. Still, her endgame is similarly to dismantle the idea that if a person undergoes pregnancy, “the product of all that pain and discomfort ‘belongs’ to her,” as Firestone wrote.

The thorniest question for all utopian family abolitionists is what would happen if, when the imagined future arrived, that possessive instinct refused to fade. Would the society, or the state, force women to hand over their children to be communally mothered? Different politics, same Handmaid’s dystopia. In the Dialectic, Firestone briefly acknowledges that the existence of “an instinct for pregnancy” would pose a problem for her project—but then she argues that, once we “sloughed off cultural superstructures,” we would discover no such innate drive.

Lewis similarly seems to believe that people would choose full surrogacy over the private family if given a choice. She writes about being sustained as a person by loving queer friendships and about being inspired as a scholar by the history of black kinship networks and the work of feminist theorists of color. She quotes the Sisterhood of Black Single Mothers, an organization of New York women in the 1970s and ’80s who proclaimed that their children “will not belong to the patriarchy. They will not belong to us either. They will belong only to themselves.”

In all these examples, Lewis sees a defiance of the idea that biology defines kinship, or that kinship entails ownership. “Everywhere about me, I can see beautiful militants hell-bent on regeneration, not self-replication,” she writes.

Self-replication certainly seems like an insufficient rationale for adding a person to the planet in its present state. I often hear the argument that having a child is a way of enacting hope in the future—despite everything—or of contributing a person who might help mend the world. Lewis’s impassioned case for full surrogacy left me thinking about how children raised communally might be better prepared for that task. After all, we’re already dependent on one another: If we were used to the idea that we belong to each other, we might act as if the crises that threaten the most vulnerable also posed a danger to the most comfortable. That may sound like a utopian pronouncement, but it’s closer to the inescapable truth.