Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak received national attention last week for vetoing a bill aimed at reforming the Electoral College. State lawmakers approved a measure that would have added Nevada to the popular vote interstate compact, pledging its six electoral votes to whoever wins the nationwide popular vote. Fourteen states plus the District of Columbia, comprising 189 electoral votes, have signed the compact. Once the compact reaches the threshold of 270 votes, it would theoretically render the Electoral College obsolete.

Sisolak said he opposed the bill because it “could diminish the role of smaller states like Nevada in national electoral contests and force Nevada’s electors to side with whoever wins the nationwide popular vote, rather than the candidate Nevadans choose.” Proponents still weren’t thrilled. New York magazine’s Eric Levitz wrote that it was “rather dispiriting to hear a Democratic governor echo one of the dumbest arguments in contemporary American politics.” ThinkProgress’ Danielle McLean warned that Sisolak had “made the road to giving all Americans a voice in the process much more difficult.”

While the compact’s defeat in Nevada may have been dispiriting to national observers, its failure shouldn’t be their biggest takeaway from the state’s legislative session. Democratic lawmakers, fresh off their clean sweep in last year’s elections, advanced progressive legislation on multiple fronts, including abortion rights, criminal-justice reform, labor rights, gun control, and more. Those victories show what other former red states can accomplish if and when Democrats secure power there.

A reliably Democratic Assembly is all that’s kept Nevada from being controlled by Republicans for the past three decades. As of last year, it had been run by Republican governors since 1999, and the Senate had been controlled by Republicans for 11 of the 16 legislative sessions dating back to 1987. The GOP even held unified control of Carson City as recently as 2016-2017—something the Democrats hadn’t enjoyed since 1992.

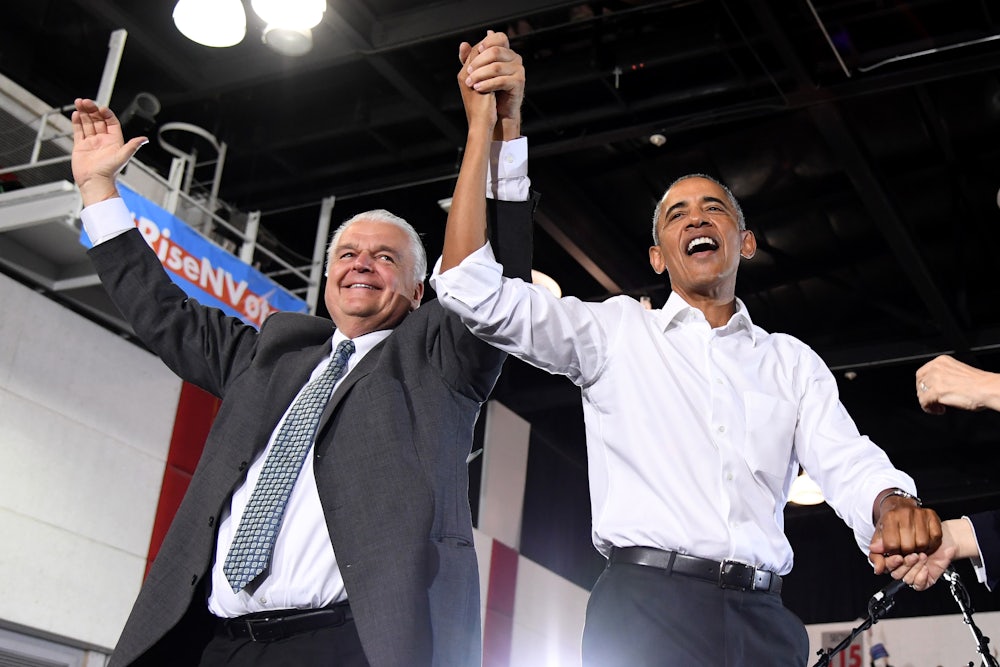

But in November’s midterms, thanks in part the anti-Trump “blue wave,” Nevadans handed Democrats a trifecta: full control of the state legislature, and installing Sisolak as governor. State Democrats broke other barriers, too. Women currently hold 52 percent of the seats in the Assembly and the state Senate, creating the first majority-women state legislature in American history. Lawmakers told The Washington Post last month that the gender shift reshaped the legislature’s approach to countless issues during this year’s session, from women’s health to gun violence.

Nevada has a part-time legislature that normally meets only once every two years for a 120-day session. By design, that limits the amount of legislation that state lawmakers are able to craft and pass every session. But the Democrats made the most of their four months at the wheel, which ended on Monday.

One of the most ambitious bills, which Sisolak signed into law last month, rolled back the state’s felon disenfranchisement laws. Nevada had one of the harshest disenfranchisement regimes before a 2017 measure created mechanisms to restore voting rights for thousands of people with felony convictions. The new law goes even further by automatically restoring voting rights to anyone not behind bars. The change will affect more than 77,000 Nevadans, amounting to roughly 4 percent of the state’s voting-age population and 12 percent of its African American electorate.

Reforming the state’s electoral system was a consistent theme for lawmakers during the session. One new law requires state demographers to use prisoners’ last residential address before incarceration when drawing legislative and congressional districts, as the state will do after next year’s census. The innocuous change effectively abolishes prison gerrymandering, a practice that gives rural areas disproportionate political influence by counting prisoners as residents when apportioning legislative seats.

While states like Georgia and Alabama passed sweeping new restrictions on abortion in recent months, Nevada was one of the few states that took the opposite approach. The Trust Women Act, which Sisolak signed into law last week, repealed the state’s moribund laws that imposed criminal penalties on doctors who provide abortions. It also repealed provisions that required doctors to inquire about a woman’s age and marital status and describe the “emotional implications” of the procedure to her before it would be performed.

In some ways, this wasn’t surprising. Nevadans already voted to entrench a women’s right to obtain the procedure in a 1990 ballot initiative, meaning that abortion would still be legal in the state even if the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade. Those provisions, combined with the state’s libertarian bent on social issues, have largely silenced the issue in state politics. Adam Laxalt, the Republican gubernatorial candidate in 2018, filed anti-abortion briefs in federal court during his tenure as the state’s attorney general, but his campaign claimed he had “zero interest” in revisiting the 1990 referendum if he were elected governor.

On gun control, Sisolak is expected to sign the legislature’s “red flag” bill, which would expand the courts’ authority to seize a person’s firearms if they’re found to be a danger to themselves or others. Looming over the contentious debate are memories of the mass shooting in Las Vegas almost two years ago, where a gunman firing from a hotel window murdered 57 people at an outdoor concert and wounded almost 900 others. State lawmakers also strengthened the state’s background-check system, implementing a ballot initiative that had been passed by Nevada voters in 2016 but went unenforced during Laxalt’s tenure as attorney general.

Lawmakers also passed a measure to phase out the state’s use of private prisons by 2022. Previous versions of the legislation attracted Democratic support, but were watered down and scrapped amid resistance from state corrections officers and a veto by Republican Governor Brian Sandoval. Supporters said it would make Nevada the fourth state to forbid the practice. Though private prisons house a small portion of American prisoners compared to state-run facilities, the industry is widely criticized as a contributor to mass incarceration.

Nevada became the fourth state to abolish what’s known as the “gay panic” defense, drawing upon a proposal by high-school students in the state’s youth legislature program. Under the new law, criminal defendants can’t use a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity as a defense to mitigate their culpability during trial. The measure is a response to cases where defendants received lighter sentences or lesser charges because they blamed their crimes on the discovery that a victim was gay or transgender.

The state legislature took aim at other problems with the criminal-justice system. The Nevada Second Chance Act will allow Nevadans to seal criminal records for most offenses if they are later decriminalized, a change largely aimed at hiding marijuana-related convictions from potential employers after the state legalized possession in 2016. Another bill signed into law removes the statute of limitations for sexual assault if DNA evidence is collected. A long-overdue measure currently awaiting the governor’s signature will compensate people who are wrongfully convicted.

The session wasn’t without disappointment for progressives. Lawmakers approved a bill giving collective-bargaining rights to state employees for the first time, but only after adding an amendment that gives the governor the final say on wages and benefits. Law-enforcement groups persuaded legislators to water down an ambitious criminal-justice reform package before sending it to Sisolek’s desk. Efforts to reform the state’s bail industry floundered after stiff resistance from the bail-bond industry. And a bill that would have abolished the death penalty failed to get a committee hearing.

Even still, Democrats racked up a healthy set of reforms in a state accustomed to long stretches of conservative rule. Nevada isn’t quite a solid-blue state yet, and deeper changes may have eluded Democratic lawmakers for now. But their victories still offer a blueprint for what’s possible to progressives in other purple states—and a reminder of what hasn’t yet been accomplished in some blue states that are still behind the curve.