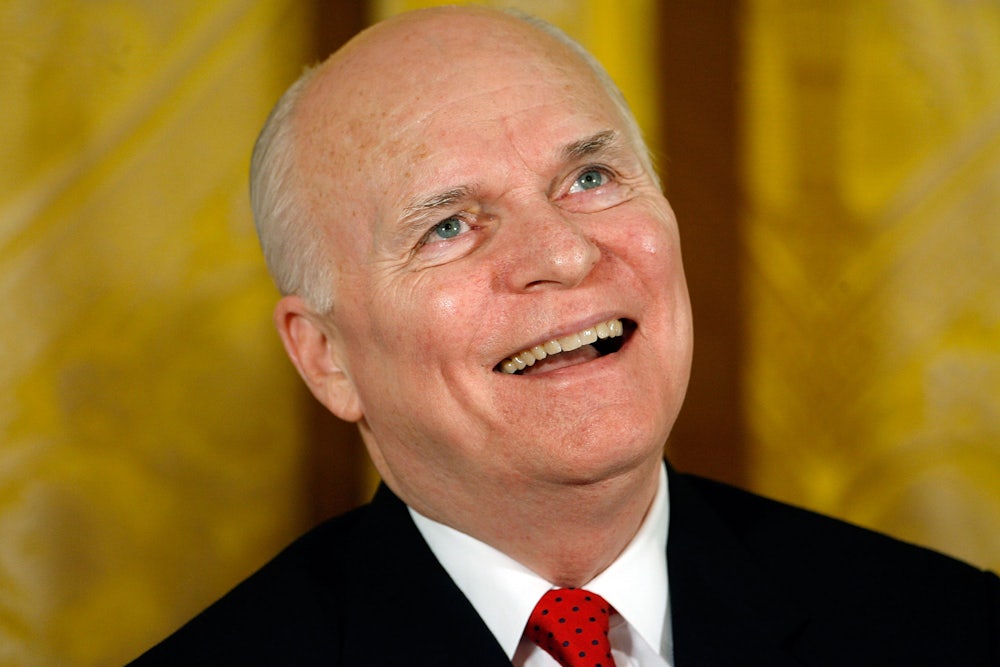

When Brian Lamb launched C-SPAN in 1979, he set into motion a multi-decade experiment in news media that was both maximalist and minimalist: wall-to-wall coverage of the American government, but unmediated by actual journalists, allowing us, the public, to decipher and decode. It was an ethos that animated Lamb’s own interviewing style, as the host of C-SPAN’S Q&A program, where he conducted his work like an informational exhibitionist, baring all, no matter the message. Lamb was not one to intrude or to object to his guest’s claims. He was so studiously neutral, so generously passive, that Christopher Hitchens once remarked that Lamb was a “fine Democrat as well as a good Republican.” Lamb himself is reluctant to identify as a journalist. “Whatever I might be,” he prefers to say.

Lamb, who was CEO of C-SPAN until 2012, stepped down this May as the host of Booknotes after conducting what he estimates to be 2,000-plus interviews in his lifetime. Lamb’s status in news journalism has long been emeritus-like, unbeholden to ratings (as a nonprofit, the network has never been monitored by Nielsen) or shareholders. He’s been free to shape the news as he sees fit—which is to say, by not shaping it at all.

But after decades of delivering this raw content to an estimated 47 million viewers a week on television, plus another 70 million online, what, if anything, has the public gained by such neutrality? And where do Lamb’s views fit into present-day concerns about a “post-truth” era in which politicians like Donald Trump have hacked the news industry’s “objective” standards to disseminate lies and propaganda? Lamb begins a defense of his methods with a promise: “You will come away very frustrated by this discussion.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Your interview style has been mythologized for your refusal to impose yourself in an exchange. Yet you’ve also been outspoken about the political class’ penchant for lying. So how did you maintain such a good-faith attitude toward your subjects over the years, during the course of thousands of interviews?

It’s probably a learned respect for the average intelligence of the American public to figure it out for themselves, right or wrong. I’m a pessimistic optimist. It’s just the way I am. Every time I said to myself, “I know that person isn’t telling the truth,” my reaction was: “So does the caller at the other end of the line.”

If there’s one thing that upsets me the most in watching a TV interview, it’s when interviewers want to inject their own opinions into a conversation. It shouldn’t come back to me. I don’t need someone to tell me what’s dumb or stupid—or not right. An interviewer can ask the question again in a different way. But stop telling me your opinion. This is journalism. If I want your opinion, I’ll read your editorial page.

There seems to be more pessimism than optimism in your telling The Wall Street Journal that “lying” is the word that best describes the Capitol.

It’s funny, that just popped out of my head, and the Journal made it their lede. At the end of the story, I said anyone who is halfway intelligent and doesn’t notice the lying is missing some brain cells.

I can’t justify it. Don’t be so cocksure that your side is telling the truth, is all. That’s the problem we have right now. The idea that there’s this imbalance in telling the truth, or that there’s only one side that’s lying to us. No, the lie is hidden, and you can hear it everywhere: “If I’m elected, I’m going to give you everything.” You are not going to give us everything! It’s impossible. It’s not there to be given, so stop lying to me. You want the public to challenge it and the media to challenge it. But it’s up to us as individuals to say “stop lying.”

Does the journalistic interview still serve a public good?

It’s vital, absolutely, but it’s just one part of the overall mix. The only reason I gave it up was age. I haven’t changed at all. I would spend 20 hours in preparation for a one-hour interview. We gotta keep trying. We gotta.

I did come to realize that interviewing a politician about a book was generally a waste of time. The book itself usually was a waste of time, written by someone else. I didn’t want to waste my time. Why would I spend an hour with someone who would lie to me? I didn’t want to have any more smoke blown in my face.

I ask about the interview because there’s a sense that this idea of challenging power, fact-checking lies, and so forth, has been a failure. It doesn’t even need repeating that President Trump has gamed this system and exploited it to great success, with the media reprinting his every word.

Let’s assume that most people in New York City can’t stand the president. Let’s assume, without going overboard, that the media world has done everything possible to try and correct his ability to game the system. If he succeeds in getting reelected, they have failed miserably because they have thrown everything they can at trying to change the opinions of the people who voted for Donald Trump.

What’s going on here is complicated, there’s no easy answer. If you hate what New Yorkers believe in, and you can say that about a lot of people, you also hate whatever the New York media crowd is trying to do to Donald Trump. I hear it all the time! “See, I told you that New York is out to get him.”

I don’t think you can call anything a failure. Have some fun and see what presidents said just weeks before they took us into world wars. The media happily published Woodrow Wilson promising to keep us out of World War I.

Do you think journalism is up to the task of handling the distortions and lies of any presidency? Do you buy into the argument that Trump is leading the press around by the nose?

I’m just not hysterical. The problem isn’t journalism doing its job right or left. The problem is that the public is not paying any attention. Today with the choices in media, the pressure is on the individual to find the information. We’ve had fantastic journalism. If The New York Times would go after the next president like they have with Trump, it would be a magnificent thing. There’s been some fantastic journalism, but you don’t have enough time in a day in a week or a month to find it all, but it’s there. It’s a great time for journalism.

Leaving aside the fact that, as far as the business side is concerned, newspapers more closely resemble a charred crater, why do you have any optimism for the future of media?

It’s simple. I have choices, now, and I know exactly what I’m getting. Before, I had to listen to people telling me they’re fair, objective, and balanced—when they weren’t. It’s why I listen to all of it—I can enjoy Rachel Maddow at the same time I enjoy Laura Ingraham. That just blows everyone away.

Think of it like this, when you walk into a bookstore, and they have 120,000 titles, you don’t say, “Gee, all of these books are really hurting the chances for those three or four classic bestsellers over there.” So few have had so much power over the years. We’re in the wild, wild west right now. It’s wide open. It’s hard for people to see it, but for the first time in my history, and in American history, you literally can get into this business without asking anyone’s permission.

For someone who preaches a kind of journalistic minimalism, what do you make of the rise of celebrity reporters? Or news-making becoming its own type of TV content, as we’re seeing with shows like The Fourth Estate?

In an industry based on the bottom line, these are stock-traded companies, it’s hard to tell somebody that they can’t do something. The bottom line matters above all other decisions. That’s why you see media people become stars. You see Peter Baker everywhere now. Reporters are everywhere. It makes sense that The New York Times has never done better in recent history, its synergistic.

It’s funny. When C-SPAN first started, the Times would not allow a camera in their newsroom. The one time I wanted to go into their newsroom, this was 25, 30 years ago, I was met at the front door by an escort. They would not permit any TV filming of the newsroom. When we went to The Washington Post to do a program on the editorial board, they allowed us to only go into a conference room. We brought two cameras and interviewed the editorial board. One of our cameras turned to show the newsroom, and one of their top editors put his hand over the camera. That was the whole attitude, then. We just wanted to show what it looked like! As much as we could, I wanted to show the public how journalism works without comment. I try to be as transparent as possible with our approach. It all goes back to the label the establishment first pinned to C-SPAN: “boring.”

In celebration of C-SPAN’s fortieth anniversary this spring, David Graham over at The Atlantic offered his congratulations by suggesting that the channel is actually an “author of today’s political chaos.” He essentially argues that televising the process, showing everything, has made it performative, not substantive. How did you respond to this?

I haven’t given that much thought. I doubt it. One person’s chaos is the next person’s choice.

The story of your earliest days in D.C. working behind the closed doors of the Pentagon press room with Robert McNamara during the Vietnam War is central to C-SPAN’s origin story. So why not defend the legacy of your experiment in terms of exposing access journalism or questionable journalistic habits like printing quotes from anonymous sources?

I just want you to know about it! I’m not opposed to any of this stuff. I’m not a moralist. I am an apologist for information. I don’t have a book that says, “This is the way journalism ought to work.” I know what it’s not, and that’s when you try and tell me that there’s some journalism bible somewhere about how it all works. You cannot moralize this stuff. There was a time when people tried to but you can’t anymore. I lived that time once already.

I can’t tell if this is an extremely realistic, or wildly defeatist, view of how the media works. Or both.

It’s probably just pessimistic. You cannot just paint every person that works in the business with the same broad brush. The guy who you ought to ask about it is Bret Stephens.

So after four decades of being accused of creating a “boring” product, can you tell me if that description ever worked its way into how you functioned as a journalist? Did it make you angry?

I don’t want to get in trouble, but I guess at this age it doesn’t matter. “Boring” probably sank in. We laugh. It’s funny. But it’s been a drumbeat over time. Boring, boring, boring. They’re over there [points toward Capitol Hill] spending $22 trillion, money we don’t have by the way, but hey, it’s boring. Let’s go back to the fun narrative on Mueller or on Trump. That’s a lot more fun because there’s blood in the water. This is all boring and serious. Even the members don’t wanna play the boring game. A chunk of prime-time TV, though? They’ll take it. That’s a lot more fun.