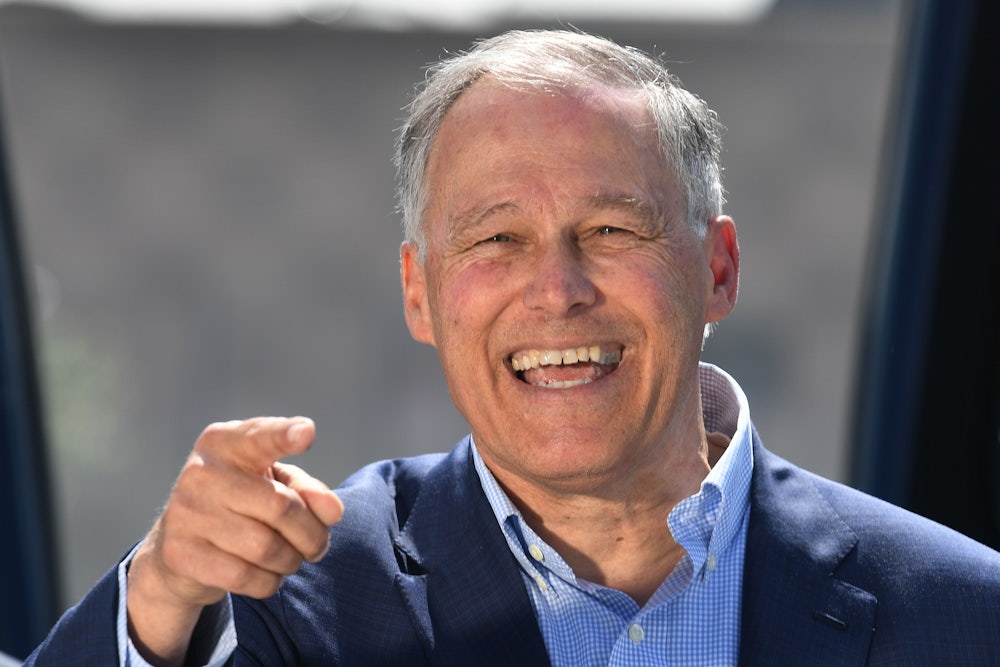

On the eve of the first-ever presidential primary debate of the 2020 election, Washington Governor Jay Inslee wasn’t holed up in a hotel room preparing talking points with his team. He was at the Frost Science Museum in Miami, practicing them on me. “We’re the last generation that can do something about this,” he tells me—and by this he means the climate crisis. It’s the only thing Inslee’s ever really interested in talking about.

If you don’t live in a forest on a mountain in the West, Washington state’s Democratic governor may be unfamiliar to you. And you wouldn’t be alone: According to one CNN poll, 73 percent of Democratic voters haven’t yet heard of Inslee, making him one of the most unrecognizable candidates in the crowded field of 20.

But Inslee’s laser-focus on slowing catastrophic global warming has been both widely covered and widely praised. New York magazine’s Eric Levitz, for example, has called him “the sanest (if not only sane) presidential candidate we’ve got.” And Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has called Inslee’s climate plan—the fourth and final part of which he released on Monday—the “gold standard.” So what’s preventing Inslee from breaking through?

Personality could be a factor. To put it in Washingtonian terms, he’s a bit Northface on the outside, Patagonia on the inside—seemingly far more comfortable in a flannel shirt than in a suit. Or perhaps, as some have speculated, it’s the simple fact that he’s just another white man trying to be president. And who wants another one of those?

But when he sat down with me on Tuesday night, Inslee seemed to admit that his candidacy isn’t actually about becoming president. It’s about bringing his ideas to solve the climate crisis into a broader view. “Right now it’s only mine,” he said of his comprehensive, 110-page plan to mobilize $9 trillion in climate-related spending in the next decade, require “zero-emission” electricity generation across the U.S. by 2035, and end America’s reliance on fossil fuels. “But I hope all of my competitors will embrace it soon and just say, ‘Hey, Jay’s got a good plan here, let’s do it.’ And then we’ll get a great nominee, and [we’ll] all get behind ‘em and get this thing done.”

It’s not a bad thing to hope for. Because compared to every other plan to fight the climate crisis out there—including the ever-popular, but endlessly vague Green New Deal—Inslee’s plan has the broadest range, and the most specific avenues toward rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions across all economic sectors. It might be, to put it simply, our best bet yet toward preserving a livable planet for future generations. And on Wednesday, Inslee will hopefully have a chance to make that case directly to the American public.

The Green New Deal may currently be the most well-known and popular climate plan in existence. But because it’s not actually legislation yet, it’s not much of a plan. And that’s why Inslee’s four-part proposal is so appealing—because it essentially takes AOC’s broad vision for a plan that takes the climate crisis seriously, and turns it into detailed, implementable policies.

In Inslee’s plan, the Green New Deal’s vague promise to create millions of new green jobs becomes $9 trillion of investment in American industries and manufacturing, infrastructure, skilled labor, and new technology deployment, some of which will be used to provide bonuses to companies providing union jobs that pay a decent wage. A commitment to zero emissions becomes a plan to sunset coal by 2031, providing funding, training, and education to support coal communities through the transition. A promise to secure access to clean air and water for all Americans becomes a plan to actually use all the teeth of the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act to enforce pollution regulation.

Inslee also came out this week with a more aggressive stance against fossil fuel companies than even the most progressive candidates have taken so far. In the “Freedom from Fossil Fuels” portion of his plan, Inslee gives voice to a lot of things that have been batted around by the far left end of the Democratic party for years: nationalizing parts of the fossil fuel industry in order to manage their shutdown, a ban on fracking, a refusal to back any sort of legal immunity for oil companies in exchange for regulation, and support for carbon pricing alongside both regulation and litigation.

Unlike the Green New Deal, however, Inslee’s climate proposal does not include universal health care. But he does recognize the need to create a health care system that works in an age of unprecedented warming, which has numerous negative health impacts. “When we act on climate change, we’re protecting our families, our health care, our economy—everything. This is not one issue. It’s every issue,” Inslee tweeted earlier in the day. That’s why Inslee also has a plan for reforming the immigration system—no surprise, given the mass migrations expected to take place due to climate and environmental factors.

The emissions crisis is indeed either a lens or a magnifier for every major issue in the United States. War? Climate change multiplies the threat of war. Health care? Climate change is a public health crisis. Immigration? Climate change is projected to create hundreds of millions of migrants by mid-century. Crime and police brutality? Both increase during heat waves—like the one oppressing Miami at the moment.

The next U.S. president will almost certainly need to contend with all of these issues through the lens of ongoing climate change. And so far, Inslee’s the only candidate who speaks frequently of those intersections. In Miami, for example, he pointed out that climate change is exacerbating a housing crisis. “I was visiting Little Haiti, where historically lower income families have lived, but you know—it’s on high ground,” he said. “So now you have developers coming in, you have people coming in who are having to leave their oceanfront homes, and it’s driving up property values and rents and the community there is being priced out.”

It’s an open question, however, whether the debate on Wednesday night will provide Inslee with the opportunity not only to talk about all these things, but to stand out if and when he does. “We have to have climate change front and center in this debate,” he told me. “We cannot allow it to be sorta pushed off to the end of the debate stage.” But there’s a good chance it could be. Despite the fact that the debate is being held in a sinking city, the Democratic National Committee has said it won’t focus this or any upcoming debate specifically on the climate crisis.

Combined with the fact that Inslee will be competing for attention with nine other candidates on Wednesday night, all of this means fleeting opportunity for Inslee to make the case that his plan is what the Green New Deal should truly be. And those opportunities are becoming more fleeting by the day. To ensure his spot in the third round of debates, Inslee needs to boost his donor count from around 80,000 to 130,000 by August. That may not happen if he doesn’t create some sort of viral moment on Wednesday night.

That moment doesn’t have to make him president, he says—it simply has to push climate change further into the national conversation. If he does that, he’ll be successful. “I wanted to be able to look my grandchildren in the face and tell them I did absolutely everything within my power to try to protect them from the climate crisis,” he said. The question is whether his fellow candidates, and the public, will follow suit.