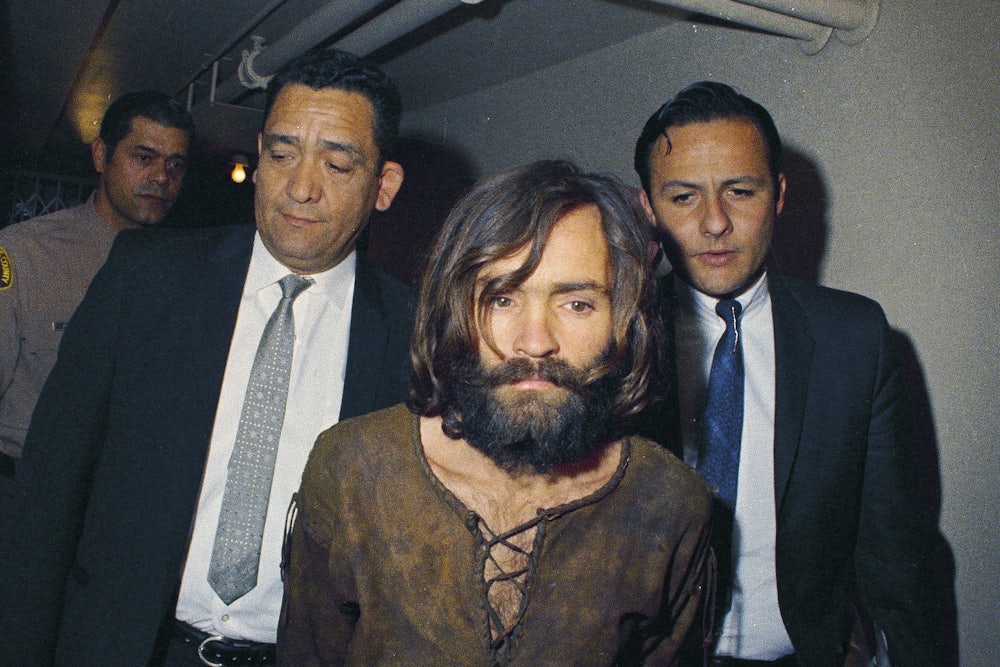

Editor’s Note: August 9 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the so-called Tate murders, when followers of Charles Manson massacred five people, including actress Sharon Tate, in a home north of Beverly Hills. These events also play a prominent role in Quentin Tarantino’s new film, Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood, although the filmmaker characteristically has rewritten what actually occurred. Given the renewed interest in Manson’s cult, we’re republishing this interview—first published by Tin House in 2017—between New Republic Editor in Chief Win McCormack and a Manson follower who left the “family” just in time.

A house on Romero Canyon Road, in the Montecito section of Santa Barbara, California, the evening of Saturday, August 9, 1969. There were five of us present: four of us—myself, Richard, Jan, and Ruth (my girlfriend that summer)—were Junior Fellows at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara, and there was Jan’s wife, Barbara. We were all in our early to mid-twenties. As dusk fell over the eucalyptus and lemon trees surrounding the house, we dropped acid. As it turned out, this was not the right night for this group of people to do that.

All afternoon the news had been filled with reports of a grisly and bizarre quintuple murder that had taken place after midnight in a mansion at 10050 Cielo Drive off Benedict Canyon in Bel-Air, an exclusive residential area of Los Angeles about eighty-five miles southeast of Santa Barbara. The mansion was the residence at that time of director Roman Polanski and his wife, actress Sharon Tate. When the police arrived that morning, they found, in the living room of the mansion, the bodies of Sharon Tate and Jay Sebring, an internationally known hair designer who was Tate’s former lover and now a friend to both her and Polanski, and on the front lawn the bodies of Abigail Folger, a Folger-coffee heiress, and her lover, Wojciech Frykowski, a playboy and friend of Polanski from his filmmaking days in Poland. Two of these victims—Sebring and Frykowski—had been shot. All four of them had been stabbed multiple times. Frykowski had also been struck on the head with a blunt instrument. The police found another victim as well, a young man named Steven Parent, who had been visiting the grounds caretaker in his nearby cottage, slumped over the wheel of a car near the gate to the property. He had been shot four times. Someone had climbed the telephone pole, with a pair of wire clippers, and cut all four telephone wires to the house. On the front door the word PIG was written in blood that, after analysis, proved to be Sharon Tate’s. Blood was everywhere—throughout the house, on the front porch, on the lawn. Witnesses described the sanguinary scene as a “battlefield” and a “human slaughterhouse.”

Since it was the midst of summer, it did not get dark until fairly late that night of August 9. By the time darkness had consumed the house on Romero Canyon Road, Richard, Jan, Barbara, Ruth, and I were fairly well stoned. Suddenly Jan, a philosophy graduate of Reed College with a strong penchant for getting caught up in twisted and protracted flights of fancy, started talking about the murders in Bel-Air. He alluded to some of the details of the murder scene and to the names of some of the victims. Then he said that even as we sat there, the murderers could be in our vicinity; in fact, they could be right outside the house at that very moment. He emphasized the fact that the murders the night before had taken place in a canyon, and we were in a canyon, and the two canyons were not that far from each other; we could easily be reached by car, just as the victims the night before must have been. He also pointed out that the number of people in our house, five, was the exact number as had been murdered at the Polanski residence. He went on about all this at some length, until we finally told him to shut up.

Even had we not been stoned on LSD, this kind of talk, under the psychological conditions prevailing in Southern California that night, would have induced paranoia in the rest of us. We stood up and went to the windows and looked out. Of course, if you look out the window of a brightly lit house into the darkness, you don’t see much of anything. Romero Canyon was an extremely quiet area, but there are always noises and, in the night, they tend to be mysterious ones. We drew all the curtains on three sides of the living room and in the dining room. We locked the doors. Then we went around the house and made sure all the windows were closed, and pulled down all the window shades. We turned out as many lights as we could and still find our way around the house, and then huddled around the dining room table for a feeling of solidarity. Every once in a while one of us got up and pulled aside a curtain a fraction and peered out to check on things. I don’t think any of us got any sleep that night.

But besides the definite feeling of menace, there was a feeling of being menaced specifically by evil, an almost palpable evil. Of course, we were not the only ones in a state of fear in Southern California that night. And as it happened, that fear was justified. Just after midnight, Rosemary and Leno LaBianca were brutally slaughtered in their home at 3301 Waverly Drive in the Los Feliz area of Los Angeles, near Griffith Park. They too were killed with multiple knife wounds. The police found a fork protruding from Leno’s stomach and a knife still piercing his throat. On a wall of the La Biancas’ house was written, in their blood, DEATH TO PIGS and RISE and HEALTER SKELTER (so misspelled). This was the news Ruth and I woke up to on Monday, after our LSD trip had wound down and we had caught up on our sleep.

Years later, in the ’80s, when I was studying and writing about the Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and his aggressive cult in central Oregon for Oregon Magazine, I had another, more direct encounter with the existence and palpability of real evil. At his ashram in India, before he came to Oregon, Rajneesh had involved his followers in prostitution throughout Asia, international drug smuggling, and violent-encounter groups in which occurred numerous rapes (in the name of sexual liberation) as well as physical abuse resulting in at least one death. Rajneesh forced his women followers into abortions and sterilizations (he didn’t countenance childbearing). In Oregon, Rajneesh followers were eventually implicated in the poisoning of restaurant patrons in The Dalles, the seat of Wasco County, with salmonella, and the attempted poisonings of two Wasco County commissioners, in a plot to gain control of the Wasco County Commission so that the incorporation of the city Rajneeshpuram, which Rajneesh megalomaniacally aspired to build, would be approved. Examining the history and behavior of Rajneesh honed my sense that evil and an evil path in life are, at least in key cases, deliberately and consciously chosen.

Rajneesh mesmerized his followers with a stupefying amalgam of Eastern mystical mumbo jumbo (Rajneesh, like Charles Manson, talked frequently about the need to “lose” or “give up” the ego) and the language and techniques of the then-prevalent humanistic psychology and human potential movements. Nathaniel Brandon, a humanistic psychologist of the era, after reading some of Rajneesh’s literature in 1978, noted that Rajneesh “explains and justifies the slaughter of Jews throughout history,” and wrote that “almost from the beginning I have had the feeling that this is a man who is deeply, deeply evil—evil on a scale almost outside the limits of the human imagination.” Rajneesh adherent Shannon Jo Ryan, whose father, Congressman Leo Ryan, was gunned down at Jonestown, once stated: “I’ve heard other people say that if [Rajneesh] asked them to kill themselves, they would do it. If [Rajneesh] asked them to kill someone else, they would do it ... I don’t know if my trust in him is that total. I would like it to be.” Rajneesh himself said the following: “When you surrender, you have surrendered all possibility of saying no. Whatsoever the situation, you will not say no.”

My sense of evil as a consciously chosen path had originated, however, in my familiarity with the Center for Feeling Therapy, a purported “therapeutic community” that flourished in Los Angeles in the ’70s. Center “therapists,” led by head “therapist” and leader Richard “Riggs” Corriere (who did not countenance childbearing among his followers either), employed a combination of abreactive/regressive psychological techniques, which they had learned from Primal Therapy guru Arthur Janov, and coercive social techniques of group therapy to gain control of their patients’ psyches and lives. (Some three hundred “patients” lived together near the therapists’ “compound” in an area of West Hollywood.) The Center for Feeling Therapy broke up in two days in late 1980 amid revelations about what had been going on behind the scenes there, including sexual and financial exploitation of patients. Afterward, while researching transcripts at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, I discovered that three Center therapists, in 1972, not long after the Center’s founding, had held something called the “Esalen Seminar on Feeling Therapy.” During this “seminar,” one of the therapists, describing the abreactive techniques they used to regress patients back to the helplessness of childhood, said that these techniques “were so powerful” that they could use them to manipulate and control their patients, “if we wanted to.” This therapist added: “Hitler did that, you know.”

One of the revelations during the Center’s breakup was that Richard Corriere had been lecturing his therapy group on the virtues of Adolph Hitler. Among other statements Corriere had made was this: “If Hitler had won World War II, he would have eventually done good for the world, because all human beings, deep down, want to do good.” Rajneesh had also alluded to Hitler (in the book The Mustard Seed, which Brandon referenced), claiming, “Jews are always in search of their Adolph Hitlers, someone who can kill them—then they feel at ease.” And Charles Manson, the evil mind behind what came to be called the “Tate-LaBianca killings,” according to his prosecutor, Vincent Bugliosi, told his followers that “Hitler had the best answer to everything” and that he was “a tuned-in guy who leveled the karma of the Jews.” The reason for such cult leaders’ fascination with Hitler seems clear enough. In his turn, Charles Manson himself has become something of a symbol and magnet for those drawn to the phenomenological power of evil. He still receives a huge volume of mail from admirers. One neo-Nazi wrote Manson that his discovery of Manson “could only be compared” to his earlier discovery of Adolph Hitler and the National Socialist Party.

When I was a senior in high school, my history teacher assigned us to watch a series of films about Hitler’s Nuremburg rallies. Sitting there in a small darkened room with a few other students, watching images of Hitler flicker on the small screen, not being present in that immense stadium with thousands of chanting people, listening to the magnetic timbre of Hitler’s voice without understanding a word of the language other than Die Juden and Judenfrei, I still found Hitler a preternaturally compelling figure, even at that distance in time. It was spooky, and not a little scary. What if you had actually been there? What if you had actually been German, and understood what he was saying? What if you felt resentment at the treatment of Germany by the Allies after World War I? What if you didn’t know any Jews personally and were suspicious of them? In any case, it might have been hard in the context of those rallies to emotionally resist Hitler’s hysterical entreaties and propaganda, especially juxtaposed with the hysterically passionate responses of the crowds. And that, I think, is what our history teacher sent us to learn about and contemplate. Which brings me to my next, and final, topic.

I choose to call it “The Dichotomy of Evil” (as opposed to “The Banality of Evil”). On the one side of my dichotomy are those, like the subject of the interview below, who manifestly did not ever consciously set out to follow the path of evil, but who were skillfully guided and manipulated in that direction by those on the other side of the dichotomy, those who combine intense charisma with a keen sense of how to find and gain control of followers, with diabolical purpose and intent. Adolph Hitler, Jim Jones, Rajneesh, Riggs Corriere, David Koresh, Charles Manson. What is the responsibility of the people on the first side of the dichotomy for the actions they have been manipulated and duped into? What is the responsibility of the German people as a whole for what happened in Germany in the ’30s and during World War II, a question that has been probed and debated endlessly? At the Esalen Institute, I once observed a Gestalt therapy session in which a grown woman was, through a painstaking—and painful—therapeutic process, reduced to a quivering, lost, lonely, sobbing child. The therapist, if he had “wanted to,” if he had possessed malign intent, could probably have taken this woman over completely at that moment and made her agree to almost anything he desired.

“Juanita” (not her actual name) was on a road trip from San Jose, California, to Mexico via Phoenix, Arizona. In Mexico she was going to try to reunite with her fiancé, from whom she was estranged. By her account, she had had a “harrowing afternoon” the day before, because her van had been broken into and her very expensive stereo system, which she had felt the immediate need to replace before the long trip ahead, stolen. Because of that and because of the state of her romantic relationship, she was, as are most people at the point they are inducted into cult organizations, in an emotionally fragile and vulnerable state. South of San Jose, she stopped to pick up a pregnant-looking hitchhiker who turned out to be accompanied by two men. All three were from the Manson Family. The woman was Susan Atkins, later one of the Tate-LaBianca killers. The essence of Juanita’s story is this: she got into the Manson cult by accident, and she got out, nine months later, not long before the murders, by another stroke of fate, in that case probably a stroke of great luck as well. The interview was conducted circa 1984–85. At that time, Juanita was happily married and a successfully practicing professional.

Win McCormack: So, Susan Atkins was the first Manson Family member you met, when you picked her and two male companions up hitchhiking in Northern California. What was she like?

Juanita: I knew her as Sadie Mae Glutz. Sadie was a kid, a twentysomething-year-old kid. I have lots of real fond memories of her. It destroys me when I think about what happened to her, because she tried real hard to do the right thing. Sort of screwed up all along the line in her choices. Sadie was in the passenger’s seat, and the guys were in the back. I remember her talking about their musical group. That was their story. They were all members of a band, and their band’s name was the Family Jams. I remember TJ [Thomas Walleman, or “TJ the Terrible”] saying, “Oh yes, we record with Dennis Wilson and the Beach Boys and we use their studios.” Dennis Wilson was very much a part of the “peripheral family.” I remember Sadie telling me very intently what a wonderful group it was and how neat, how much it meant to her, and how it really worked as her family. I talked to her about Mexico and how I was engaged to a guy living there. This was the end of September 1968. I was going to be 24 the next month. She talked to me about how wonderful this place was where they lived near Los Angeles. She talked with the fervor of somebody who’d been converted. [Editor’s note: Susan Atkins was involved in the Tate murders and the prior murder of Gary Hinman, a graduate student who dealt drugs to the Family. As recounted in Vincent Bugliosi’s book Helter Skelter and in The Family by Ed Sanders, during the Hinman killing, after Manson follower Bobby Beausoleil stabbed Hinman twice in the chest and he lay bleeding to death, Atkins put a pillow over his head to suffocate him. Regarding the killing of Sharon Tate through multiple stab wounds from several different knives, which Atkins participated in, Atkins once recounted to a cell mate how pregnant Sharon Tate had begged for her life and the life of her baby, and how she had responded: “Look, bitch, I don’t care about you. I don’t care if you’re going to have a baby. You’d better be ready. You’re going to die.” She went on to say that the first time she stabbed Tate, “It felt so good.”]

WM: Tell me about your first encounter with Charles Manson.

J: My intention had been to drop the three of them off and to drive on to Phoenix on the way to Mexico to hook up with my fiancé. I totally misjudged how long it would take to drive the length of California, and so by the time we drove into Spahn’s Movie Ranch near Los Angeles, I was exhausted. They said, “Why don’t you stay here?” There was a whole sort of facade of Western town buildings and then off to the right was a trailer with its lights on. Everybody said, “Let’s go get Charlie, let’s wake up Charlie,” and everyone went running in. Charlie came out naked. He had been making love to a woman named Gypsy, and she also came out naked. Nobody reacted to that. Nobody thought anything of this. It seemed like the most noticeable thing to me. Everyone was hugging each other, everybody was so happy to see everybody else. They said, “Oh, look what we found, look who we found,” and introduced me to Charlie. And he came over and put his arms around me and said how glad he was. Of course, this was the ’60s, when everybody was hugging, but there really was a lot of love around that trailer. There was real bonding. It’s that same kind of stuff, that same kind of open and unthinking love that you see in the face of a Moonie. Charlie got a guitar out and everybody started singing. It was just wonderful fun, but it was very clear that nobody had any talent. I felt perfectly comfortable with them. That night, Charlie asked if he could spend the night with me in the camper and I told him no. He let me know that I was being selfish and self-centered and that there was a deficit in my character.

WM: You decided to stick around there rather than driving on to Phoenix and then Mexico to meet up with your fiancé as you had planned. Why?

J: The wooing began almost immediately. Somebody came along and brought me breakfast, then Charlie came along and brought me coffee. From dawn on I had somebody around to tell me how wonderful it was there and I don’t think I ever spent another five minutes alone until several weeks later. At the time, this was a group of people who lived my philosophy—make love, not war—all of those things. At least, to all appearances that’s what they did! Life on the ranch then was just one great big make-believe time. There was a real spring back in the woods. You’d take a shower under a waterfall. You could run through the woods naked. There were horses to ride. It was a magical kind of place.

WM: You became one of Charlie’s lovers very quickly, I believe. How did that happen?

J: I didn’t know then how to say no to anybody. And then I was real needy too. And here were all these girls, women, falling all over him. And it was my door he was knocking on.

We went off to Malibu in my camper just a few days after I had gotten there. A man called Chuck, and Sadie and Charlie and I. My camper was one of those pop-up ones with a bunk at the top and a bunk at the bottom. And we had gone over there and dropped some acid. We spent the night there on the beach, and in the morning, when dawn was breaking, as it were, Charlie and I started making love, and Charlie told Chuck and Sadie to come down into the same bunk we were in. And I tolerated that, although we did not have group sex. I tolerated that, and that seemed to be significant to Charlie. And I remember after that Chuck and I went for a walk on the beach, and I said, “What’s this guy all about?” And Chuck said he was this really powerful, wonderful person.

He was a good lover. Probably the most phenomenal lover I’ve ever had. But once I was hooked, he didn’t have much to do with me.

WM: What made Charlie such a good lover?

J: What makes anyone a good lover? He was very tender.

WM: Charles Manson was tender?

J: Very. I never saw that man do anything that was hurtful. I really didn’t. There is a very incongruous aspect to all this for me.

WM: Tell me more about Charlie.

J: He was not particularly big—probably five-two. Really wiry, real agile. Almost leprechaunish in some ways, with a quick wit. There was a real playful quality about him, an endearing quality about him. He could be very much the little boy, and he showed a vulnerable side that really got you engaged in taking care of him.

WM: How did he show his vulnerable side?

J: I remember one time—this was at Spahn’s, and it was even very possibly that same night I gave him all my money. There were kittens all over the place. The mother cat had stopped cleaning up after them. They had messed in the kitchen. And Charlie got down on his hands and knees and cleaned the kitchen floor. He cleaned up after the kittens. He picked them up and put them inside his shirt and went and sat by the fire and warmed the kittens and played mother cat. I remember him looking up and saying, “I now understand the pain of too much tenderness, because it hurts not to hug them. But if I were to hug them I would hurt them.” It was those kinds of things. He showed himself or acted like a very, very gentle man that would never hurt anything.

WM: Would he cry?

J: I did see him cry one time. There was one night, again at Spahn’s, where everybody took megadoses of acid and probably some mescaline or something else mixed in with it. Things got really out of hand. I mean really royally. The hallucination that I had that night was one of being in a tent in Arabia where horses were jumping through the tents and all this wild pandemonium was going on. People were hitting each other. The place was literally destroyed. I remember Little Paul Watkins hit me that night. There was pandemonium. Everybody was on their own trip. And Charlie came in to get a pair of shoes and he said to me, “I can’t stay here, because there’s no love here anymore.” He said, “Tomorrow you have to tell them that they drove me away.” And the tears were just flowing down his face. I asked him to stay, and he said no, he couldn’t stay. He said that the animal had come out in them and that love had fled.

WM: You say you gave him all your money?

J: It was amazing how quickly Charlie read me. He seemed to know all the right buttons to push. Within a month I’d signed over my camper and something like a sixteen-thousand-dollar trust fund, which in 1968 wasn’t small potatoes.

WM: How did he get you to do that?

J: That’s a question I’ve asked myself many times. Some of it was drug-induced, I’m sure. I can remember the night that I told him he could have the money. That day, we started early dropping acid and doing all those kinds of wonderful things. He had been telling me that the thing that stood between me and total peace of mind and heart was Daddy’s money—I was not going to be free of Daddy until I got free of Daddy’s money. Charlie started [saying] that I was my father’s ego. And I remember thinking, That doesn’t make any sense to me. Then later I convinced myself that it probably was [right], because Charlie was always right. Charlie never openly said that he was the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, but if he didn’t say it, he sure to hell implied it. He would say things about having flashbacks about having the nails driven in through his wrists. He said, “The nails weren’t put in my palms, they were put into my wrists.” And, “They always lie to us. Everything’s 180 degrees from the way they told you it was. And there is no difference between Jesus and the devil. So your daddy would say I’m the devil, but of course I am, because if they told you that good was right, then obviously evil is right. So then I must be the devil, because I’m right.”

One of the things we did with my money, which I still feel real good about, was [take care of] the sweet old man who owned that ranch, George Spahn. All of us lived there for free and ran the place for him, because George was blind and 86 years old. We cooked for him, and we washed his clothes, and we gave him back rubs and we told him how wonderful he was. George was in danger of losing the ranch to back taxes. He hadn’t paid taxes and it was coming down to the wire—pay up or lose it. I signed over the money to Charlie and we paid six years’ worth of taxes on it. [editor’s note: Bugliosi says in Helter Skelter that one of the ways the Family kept Spahn happy was by having Squeaky Fromme—the Family member who subsequently tried to assassinate President Ford—and other Manson girls minister to him sexually “night after night.”]

WM: Did you get to know Leslie Van Houten?

J: Leslie was just a really sweet, personable girl. She had short dark hair and this bubbly way about her. Her father had been or still was a big muckety-muck architect or something in Los Angeles. And my parents were very conservative and very pro-establishment, so she and I used to talk about how no matter what we did, we couldn’t be good enough to please these outrageous parents of ours. I remember the last time I saw her we were all out in the desert and we were sitting around the kitchen in the ranch, and Leslie was talking about how we really were her family now, and how she had never felt so close to any of her blood relatives. I just remember how close to her I felt. I really liked her. I think a lot of us always were in awe of each other. [editor’s note: Leslie Van Houten participated in the killing of Rosemary LaBianca—albeit apparently somewhat reluctantly, at first. As described in The Family: “Leslie was not participating. Tex [Watson] wanted Leslie to stab. So did Katie [Patricia Krenwinkel]. Leslie was very hesitant but they kept suggesting it. She made a stab to the buttocks. Then she kept stabbing, sixteen times. Later the nineteen-year-old girl from Cedar Falls, Iowa, would write poems about it.”]

WM: Did you know Tex Watson well?

J: Tex was the mildest-mannered, most polite human being you’ve ever seen. He was one of those people that called you “ma’am” all the time, called everybody ma’am. He was from Texas. Real handsome but sort of baby-faced handsome. He wanted to go back to school or do something, and Charlie kept telling him not to bother, that it was a waste of time. I remember talking about him wanting to go back to school. I remember, when I heard that he was involved in the murders, being very surprised because he was just this really sweet guy. [editor’s note: By the accounts of Sanders and Bugliosi, Tex Watson was not only the leader but also the most savage and bloodthirsty member of the Tate and LaBianca death squads. At the Polanski/Tate property he shot Steven Parent four times in the head; shot Jay Sebring in the armpit and then drop-kicked him in the nose before stabbing him four times; sliced Abigail Folger’s neck, smashed her head with the butt of his pistol, and stabbed her in various parts of her chest and abdomen; shot Wojciech Frykowski below the left axilla and then finished him off by stabbing him in the left side of his body; and was one of those involved in stabbing Sharon Tate sixteen times. He personally killed Leno LaBianca by slashing him four times in the throat. When he had first come upon Frykowski and Frykowski asked him who he was, he replied, “I am the devil and I am here to do the devil’s work.”]

WM: Getting back to Charlie, in addition to his expressing kinship or identification with the devil, did he ever talk about Hitler? A number of leaders of destructive cults over the years have expressed admiration for Hitler, and particularly of his treatment of Jews.

J: I remember Charlie talk[ing] about Hitler having been right—that the world needed a big purging every once in a while. And I remember saying to Charlie, “If Hitler were here now I’d be dead.” And he just laughed and said, “No, you missed the point. It’s got nothing to do with whether or not you’ve got Jewish blood. It has to do with purging the world, and having only people who can survive—the only thing that was wrong with those people is that they weren’t smart enough to figure out how to escape it.”

WM: Manson also talked a lot about race wars, didn’t he? Wasn’t that the foundation for his “Helter Skelter” ideology and ultimately what led the Family to murder?

J: What was going to happen in this backward world to make it right was that the black man, who had been oppressed for years, was going to become the superior race, and the blacks would rule the world. “Helter Skelter” was Charlie’s plan for and name for their uprising and also, it turned out, apparently, for the murders which he hoped would provoke that. [editor’s note: Manson hoped that the murders would be thought to have been committed by blacks, bringing even further oppression down on them, in turn provoking them to rise up.] The reason we had to find a place in the desert was we had to have a place to run and hide, because as whites we were going to be killed or enslaved unless we were smart enough to find a place to live until—until it all balanced out. Eventually the black man would ask Charlie and the Family to take over, because he wouldn’t be able to rule on his own.

We didn’t call it “Helter Skelter” until the Beatles record came down, and then it was, “Aha, look at that—our prophets.” It’s only in the last two years that I’ve even been able to tolerate listening to The White Album.

WM: Was that really going on, what Helter Skelter describes as the mental preparation and buildup for the murders—playing the songs “Helter Skelter,” “Piggies,” “Revolution 9,” and “Blackbird” from that album over and over? The line in “Blackbird” that goes, “All your life, you have only waited for this moment to arise,” which supposedly referred to the rising up of the blacks?

J: All of that was going on.

WM: When did you first go to the desert, or, more specifically, to the Barker Ranch in Death Valley?

J: Sometime in October. Halloween weekend of 1968, I think, was when we first went to the desert. Then, in February of ’69, everyone went back to Spahn Ranch except for me and Brooks Poston, who had been one of the stable-hands at Spahn’s, who always wanted to join the Family, but Charlie had never truly accepted him.

So Brooks and I stayed at Barker. They were supposed to get us in ten days, but nobody had ever come back from Spahn’s. We were there alone when Paul Crockett and [his partner] showed up. They came on March 10 or 11. They had pulled up to the farmhouse and it was difficult for us to either invite them in or send them away. We couldn’t do either. And Paul said that was his first clue [that we were under the influence of mind control]. We didn’t know how to think for ourselves or make decisions for ourselves at all. We came out and told them that the place was taken. But Paul just said, Well, it’s night, code of the desert, and all that sort of stuff. He and [his partner] had food, and we had very little. [editor’s note: Juanita later married Paul Crockett’s partner, whose name is being withheld here for purposes of anonymity.]

WM: What were they doing up in the desert?

J: Prospecting for gold. Paul Crockett had studied with one of the early, early people who were of Ron Hubbard’s ilk—one of the first five people that L. Ron Hubbard, later the founder of Scientology, had studied with himself. This man had known Ron Hubbard when he used to say things like, “Well, you know how to really make it in this world is to start your own religion. Nobody can touch you, and you can really do it. Maybe I ought to take this stuff and can it.” And that man had told Paul the reason he wasn’t a Scientologist was that he didn’t like the amount of control that was happening in that organization.

WM: In other words, Paul Crockett knew a thing or two about cults and brainwashing. And also deprogramming?

J: Paul essentially deprogrammed Brooks and me, and later Paul Watkins, Charlie’s sometime right-hand man. One of the things that he talked about was the way Charlie got control over everybody by getting people to agree that he was something spectacular, and agree to his other self-serving ideas. He said that agreements are much more powerful than people realize they are, and that implied agreements are more powerful than overt agreements. It was those implied agreements that were making it very difficult for us to break away from him. Paul and Brooks and I used to stay up until one, two, three o’clock in the morning just talking. Doing what were early Scientology experiments. I don’t know whether they’re still done. I don’t know anything about Scientology now at all, other than the fact that Paul has warned me not to get involved with them, because they are as hard to get away from as Charlie was. [editor’s note: According to Bugliosi, Manson went through Scientology training while in prison in the late ’50s and early ’60s, and claimed to have achieved Scientology’s highest level, “Theta Clear.” Bugliosi also claims that Manson often used the phrase “cease to exist,” a Scientology exhortation.]

WM: So how did you finally extricate yourself from the Family?

J: Well, one day Paul Watkins showed up from Spahn with a woman named Barbara. They were very interested in Brooks and me and what had happened to us, because it was very clear to them that we were alive again. It was also very clear to us that they weren’t alive. Barbara—Bo—was somebody that always fought Charlie. She just wouldn’t give up, she just wouldn’t give in. And he worked on her and worked on her and worked on her. One time she was stoned and we were all sitting with the fire going and sort of chanting and I remember her really freaking out and saying, “You’re all evil, this is hell,” and Charlie saying, “Well, of course it’s hell. Remember everything that Mommy ever taught you is wrong. Where you want to be is hell. And we’re all devils.” I remember Barbara standing there and screaming at him, “I’m not going to do it. I’m not going to give myself away to you.” Yet she stayed.

The word was that they had been sent up to get us and to bring us home, to bring us back down. And we told them we weren’t going. And they stayed for several days, ostensibly to talk us into going. But it was very, very clear that they really wanted to find out what had happened. And Bo in particular just kept saying, “You’re really staying here, and you’re happy?” And I kept saying, “Yeah, I am.” Paul Crocket gave them just enough to make them interested in breaking away and getting some sense of individuality again. But Paul Watkins said, “No, I’ve got to go back and see Charlie. We’re not looking forward to telling him that Brooks and Juanita aren’t coming back.”

WM: How did you leave it with Charlie?

J: Brooks and I asked Paul [Watkins] to do something very specific. We asked him to wait until the whole Family was together at night, when everybody was there, and to say that we wanted Charlie to release us from any agreements we had made with him, and that we in turn would release him from any agreements he had made with us. We asked him to do it in front of everybody because Charlie couldn’t turn down requests in front of everybody, because he was the servant and not the leader, according to his teaching. He said, “Of course. They’re released. Nobody has any agreements to us, to me.” He said, “I don’t have any holds on anybody.” And so Watkins said, “Well, then, do you release me from any agreements with you?” And Charlie said, “Of course.” And Barbara said, “And me?” And Charlie said, “Yeah.” And Paul looked around the room at the rest of the Family members—this is the way he told the story—and said, “And what about them?” And Charlie said, “Enough of this shit about agreements,” and wouldn’t release anybody else.

Paul came back up in June, escaped, and never went back to Manson. I never saw or heard of Bo again. It was at Barker Ranch, by the way, that Charlie was arrested.

WM: You and your future husband left Barker Ranch in June of 1969 and the sensational murders took place that August. When did you hear about them and what was your reaction?

J: My future husband and I went off to some place out near Baker, California, to look for turquoise, and then to Kingman, Arizona, where his brother lived, to stay for a while and work. And that’s where we were the August weekend that the murders happened. I’m watching the television and the news broadcaster is saying how bizarre the murders were, and that there was a place on this door where the word PIG had been written. And I looked at that and said, “It doesn’t say ‘pig,’ it says ‘die.’” [editor’s note: It did in fact say “pig.” The word was written in Sharon Tate’s blood.] I just somehow knew it was them. It had been at least since February since I had seen any of them, other than Paul and Barbara, or had any contact with any of them, except for one phone call. It was intuitive, because it didn’t make sense. It was totally incongruous to what they said and how they lived when I was there. But at the same time, I looked at that. I was sure it didn’t say “pig,” that it said “die.” And that was a big part of it—there was this whole thing of you had to die and be reborn. Until you could let your old ego die and be reborn, you couldn’t be free. There was this whole thing of dropping acid and experiencing death. And I remember these people writhing on the floor, and Charlie saying, “Die, let yourself go. Die.” Standing there and looking at them: “Die, die.”

I remember that experience. I’m a very quick study. That’s how he got my money so fast. But I remember being back at Spahn’s Ranch, way back, the first couple of weeks I was there—when Charlie was telling me to die. And he said, “All you have to do is just go with me and I’ll take you, because I’ve already died. I’m not afraid.” He just stared at me. And I just stared at him. The intensity of that man’s eyes. I had literally given myself away to him by then.

WM: You never saw a sadistic or brutal or psychopathic side to Manson?

J: No. It’s one of the things that’s scariest of all. The person that I saw was, for all outward appearances, everything he said he was. He’d give you the shirt off his back, literally. He got down on his hands and knees and cleaned up cat shit. I never saw this other side of him.

WM: The whole thing must be haunting for you.

J: Have you ever read anything about the Vietnam vet survivor-guilt business? I have survivor guilt. Real survivor guilt. Leslie and Sadie are in prison and I’m living a relatively nice lifestyle. I mean, why me? How did I get out? Why did I get out? Why did they get caught? I don’t know that either.

WM: Did you ever see Charlie again, on television?

J: I saw him during the trial, on television. And it was real scary for me. He was angry and intense. Very different than I had seen him. If anybody had said to me in July of that year that these murders would happen, I would have told them that they were full of it. I would have told them that it was impossible.

WM: What if you’d been there? What if you hadn’t been deprogrammed? Do you think that you would have been involved in the murders?

J: My fear is that if I were there I’d be in jail now too. Because I pretty well did whatever he told me to do. I mean, for me to walk forty miles, as I did one time—I had blisters on the soles of my feet that were two and a half inches in diameter ... because Charlie wanted me to go somewhere and I didn’t have a car, so I walked. The basic programming was that you had to die to be freed anyway, so death was not something to be afraid of. That we were all members of one greater consciousness. But the other thing was that if Charlie said, “Jump,” my only question would be: “How high?”