The recession alarm bells are sounding. Anxiety about the direction of the global economy has been growing for some time, amid concern about President Trump’s trade war with China, economic slowdowns in major economies like China and Germany, and Brexit. On Wednesday, the country received perhaps the strongest signal yet of an upcoming recession when the yield curve briefly inverted and the returns for short-term U.S. bonds eclipsed those of long-term investments. Though the sample size is limited, an inverted yield curve has preceded recessions for the past half-century, most recently in 2006 and 2007.

Most of the speculation about the political impact of a recession has rightly focused on Donald Trump, who has, over the course of his presidency, clung to the roaring economy like a talisman. For much of his term, Trump has repeatedly pointed toward the economy and, in particular, the stock market, citing it as a kind of unofficial approval rating—proof that he was doing a good job, even as more traditional metrics suggested most of the country thought otherwise. There have been some signs that, in the rare instances when his administration isn’t being subsumed by a scandal or a tweet, the president’s approval will tick upward, likely because of the performance of the economy.

For months, Trump’s allies have been making this case explicitly, telling Politico in December, for instance, that “his reelection prospects hinge in large part on how Americans judge their economic prospects at the time of the next election.” Understanding this himself, Trump has been searching for someone to blame if the economy tanks for months, settling predictably on Democrats, the media, and Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. Those accusations have gained little traction, however, and they are unlikely to influence many outside of his base should the economy lurch into recession.

But while most of the prognostication has focused on Trump, a recession would have an enormous effect on both the ongoing 2020 race and, potentially, the next Democratic administration. As the primary season has heated up, Democrats have understandably spent a lot of energy on the hopey, changey stuff, with many arguing for transformative social and economic policies. But given the warning signs, Democrats must also prepare for the likelihood that the next president will preside over an economy in recession.

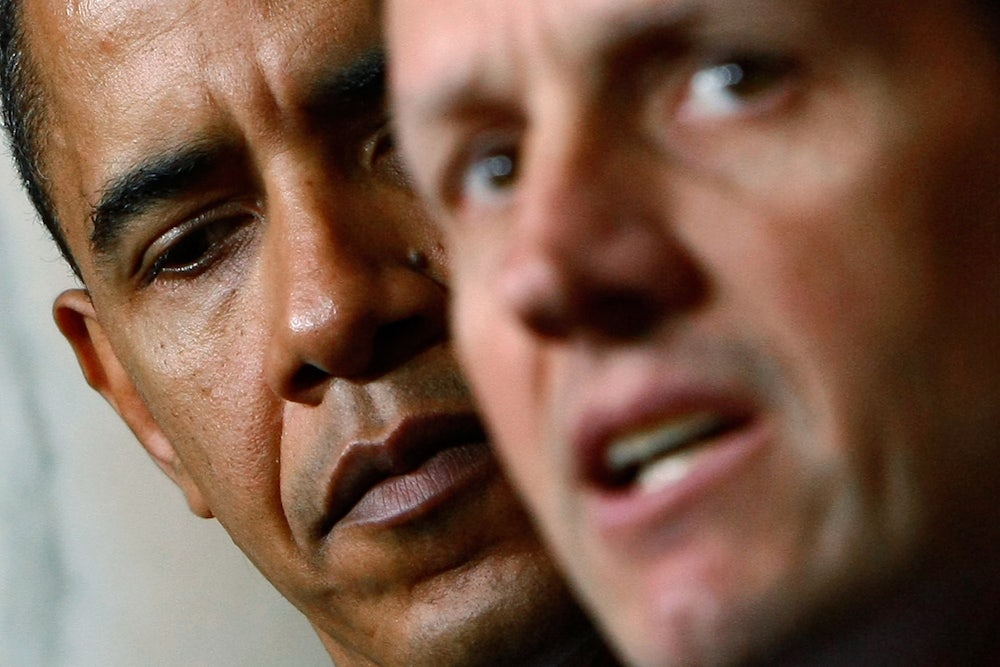

They would be wise to start by examining the Obama administration’s reaction to the last recession. Although President Barack Obama is credited with staving off the worst effects of what is now known as the Great Recession—and perhaps averting a second coming of the Great Depression—his administration’s handling of the downturn was also remarkably tepid and unambitious. “While many voters hoped Obama’s policies might represent a dramatic change along the lines of the New Deal, instead Obama acquiesced to emergency considerations and ideological blandishments aimed at tempering expectations and a return to ‘normalcy,’” Eric Rauchway wrote in the Boston Review.

Obama turned to political and economic veterans, handing the task of fixing the economy to a cabal of financial titans, many of whom played a central role in destroying it. Those insiders promptly set about propping up a deeply inequitable economic system rather than pressing for the “change” Obama had made central to his campaign. Main Street got by while Wall Street got rich … or richer. Banks were bailed out but homeowners were not. A decade later, tens (if not hundreds) of millions of Americans are still feeling the effects of the recession, while financial firms have been raking in record profits. “We can either have a rational resolution to the foreclosure crisis, or we can preserve the capital structure of the banks. We can’t do both,” Damon Silvers, vice chairman of the independent Congressional Oversight Panel told the Treasury in 2010. The administration chose the banks. Similarly, the decision not to prosecute anyone involved in wrecking the economy was an abdication of justice, one that has led to a continuation of predatory practices that will undoubtedly exacerbate the coming economic downturn.

There were real consequences for those decisions. The economic recovery was slower than it might have been, had more serious action been taken. Although a number of factors went into the Democrats’ 2010 midterm shellacking, the slow pace of the recovery, combined with the Obama administration’s decision to reward the financial sector, played a significant role. As a result, the Democratic supermajority—something the party might not see again for a generation or more—was squandered.

Democrats have a difficult task in addressing the possibility of a recession. For one, while a downturn would likely improve their (already fairly rosy) electoral prospects, they cannot be seen as eager for economic pain. At the same time, there has been a real reluctance to criticize the Obama administration’s legacy, given his extraordinary popularity among voters. Similarly, the bromide that Obama “saved” the economy would undoubtedly be hurled at any Democrat who pointed out that administration’s many blunders.

Still, there are many opportunities to make the case for a different approach, even if the presidential hopefuls don’t explicitly criticize the administration. One of the most interesting was proposed on Thursday by Slate’s Jordan Weissman, who argued that the country could ward off a recession and embark on the necessary infrastructure improvements needed to meet the existential imperative of fighting climate change:

One obvious way to fix situation A would be for the U.S. to ... borrow tons of money at low interest rates, and spend it on stuff we need. Trump wants a $1 trillion infrastructure plan? Fine. Now’s the time to debt-finance it. We can afford it, and it might help both the U.S. and the world economy avoid a downturn. This would also be a very good time to finance an expansive plan to combat climate change. Borrow a few trillion, throw it in a giant Green New Deal fund, and use it to pay for the sort of aggressive action necessary to eventually reach zero net emissions.

This approach would essentially merge recession-fighting with the kinds of ambitious policies being proposed by candidates like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. It would also be a marked contrast to what we know will come from the president—whining and more tax cuts for the rich.

Whatever the approach, however, Democrats should begin to lay out their plans now. In 2008, Barack Obama won in part by promising generational change; in office, in the midst of a recession, he empowered a bunch of bankers to restore a busted system. That can’t happen again.