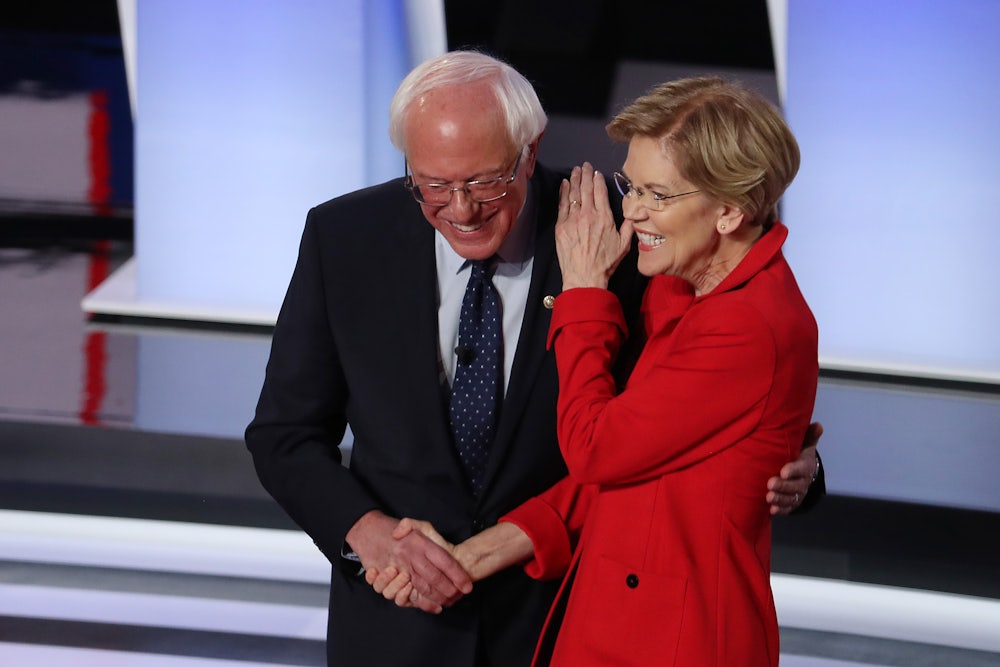

Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren agree on many things, at least when compared to their fellow candidates. But Thursday’s debate included a quick moment that highlighted how they diverge in one key area: how political power in the United States is structured, and how those structures should change.

It came during a debate about gun control and why lawmakers have thus far failed to advance a bill on the issue. “We have a Congress that is beholden to the gun industry,” Warren said. “And unless we’re willing to address that head-on and roll back the filibuster, we’re not going to get anything done on guns. I was in the United States Senate when 54 senators said let’s do background checks, let’s get rid of assault weapons, and with 54 senators, it failed because of the filibuster.”

In April, Warren became the first major Democratic candidate to call for the arcane procedural mechanism to be scrapped. It’s a logical stance for the Massachusetts senator on two levels. Her campaign is structured around the idea that the U.S. political system needs systemic democratic reforms, and the filibuster is an archetypal example of its flaws. More to the point, the GOP’s structural advantage in the Senate means that the filibuster would effectively doom any major legislation that Warren and her rivals hope to pass.

Sanders isn’t afraid to call for major changes to American society and politics. But when it comes to filibuster reform, he’s less enthusiastic for it than even some of his party’s moderates. “No,” Sanders replied when asked by a moderator if he supported its abolition. “But what I would support, absolutely, is passing major legislation, the gun legislation the people here are talking about—Medicare for All, climate change legislation that saves the planet. I will not wait for 60 votes to make that happen, and you can do it in a variety of ways. You can do that through budget reconciliation law. You have a vice president who will, in fact, tell the Senate what is appropriate and what is not, what is in order and what is not.”

What makes Sanders’s answer so unusual is that it’s simultaneously less radical and more radical than what Warren and other candidates have proposed. Filibuster reform doesn’t yet enjoy widespread support among Senate Democrats, but its proponents are growing in numbers. Harry Reid, the former Senate majority leader, even called for it to be scrapped last month in a New York Times op-ed. “If a Democratic president wants to tackle the most important issues facing our country, then he or she must have the ability to do so—and that means curtailing Republicans’ ability to stifle the will of the American people,” he wrote.

At the same time, Sanders’s proposed solution to the problem posed by Mitch McConnell’s hardball tactics is even more audacious than what his rivals have proposed. The reconciliation process allows certain budget-related pieces of legislation to pass through the Senate by majority vote instead of the 60-vote filibuster threshold. This is how Republicans brought the failed health-care bills up for a vote in 2017.

By rule, reconciliation can only be used if the legislation in question meets certain deficit-related criteria. The Senate’s parliamentarian normally decides what can or can’t be passed through reconciliation. Sanders would bypass this roadblock by simply instructing the vice president—the Senate’s presiding officer—to disregard the parliamentarian’s judgment and allow the bills to come up for a majority vote anyways. It’s a step further than anything McConnell—or President Donald Trump—has suggested. In practical terms, this would also remove the filibuster as a potent force in American politics—but at the cost of destabilizing much of the Senate’s rules and procedures under future vice presidents.

“I would remind everyone that the budget reconciliation process, with 50 votes, has been used time and time again to pass major legislation and that under our Constitution and the rules of the Senate, it is the vice president who determines what is and is not permissible under budget reconciliation,” Sanders’s campaign said in a statement last week. “While a president does not have the power to abolish the filibuster, I can tell you that a vice president in a Bernie Sanders administration will determine that a Green New Deal and Medicare for All can pass through the Senate under reconciliation and is not in violation of the rules.”

Both of these candidates would ultimately change how the Senate works. Warren’s approach to structural reforms best resembles a scalpel, making careful changes beneath the surface that rework the system without completely upending it. For Sanders, breaking what he describes as a corrupt, oligarchic system will take a sledgehammer. What will decide the Democratic nomination is whether the party faithful prefers the reformist or the revolutionary.