Photographs are not allowed at the New York Public Library’s exhibition about J.D. Salinger. You have to leave your cellphone outside the small jewel box room where the library has installed a smattering of what some might call artifacts and others might call relics (as that term applies to, say, slivers of the True Cross). You’re not supposed to document the show because J.D. Salinger would not have liked that. But of course, J.D. Salinger would have hated this whole enterprise.

Devotees will have to reconcile their desire to respect the man’s privacy, so fiercely guarded during his life, and their curiosity. But nostalgia is potent stuff. Salinger presumably still attracts committed fans, but the show for me (and I imagine for most) is an exercise in revisiting the period when I first encountered Salinger. Rereading him now in search of the profound feeling I had poring over Franny and Zooey at age 15 is inevitably a letdown, akin to when I try to listen to The Cure: a bit of I liked this? and an embarrassed affection for the skinny gay kid in a suburban bedroom I once was. It is hard for me to believe now, but I was the sort of fan who dug around in the library for the 1965 issue of The New Yorker containing the uncollected Salinger story “Hapworth 16, 1924.”

The show gives us what I guess we always wanted: the guy’s baby pictures, a copper bowl he made one summer at camp, letters to military school chums, some sea glass he picked up from the coast of Devon while in the Army. There’s professional correspondence, and galleys, and typescripts, and a bookcase from Salinger’s bedroom containing the volumes he read at the end of his life. It’s precisely like the curtains parting to reveal the great and powerful Oz as just ... some guy. It’s all immensely valuable to scholars (maybe?) and definitely none of our business.

The exhibition contains a letter Salinger wrote to decline an appearance: “It’s an old and serious (and tiresome) principle of mine not to drop by anywhere as a writer or writerly type.” Seeing this show as an adult who also writes books for a living, I felt a yearning for an era I find impossible to imagine: when publishing was a genteel business of onionskin pages and overflowing ashtrays, and a writer could survive on the largesse of William Shawn and Raoul Fleischmann, all the while maintaining a principled objection to being a writerly type.

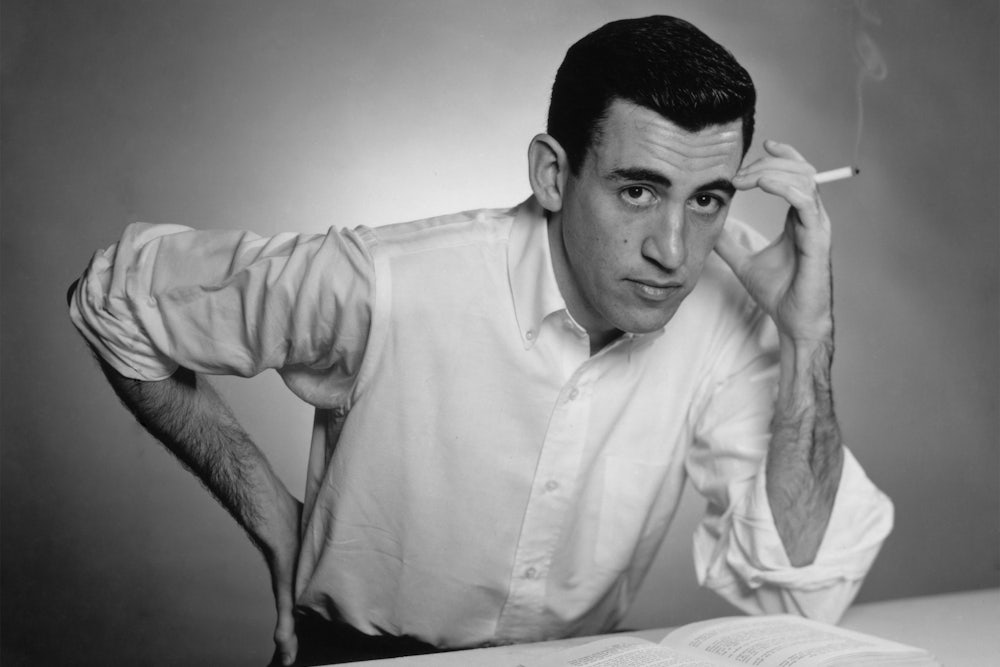

J.D. Salinger wanted to be a man, not a persona. But the fact that he published so little (one novel, a short story collection, a book containing two short stories, and a book containing two pretty awful novellas) got tangled up with his desire for some ideal, artistic purity. The guy burnished mystique into legend. He hated performing as a writer, but the role of J.D. Salinger was still a decades-long performance, one so wholly inhabited it’s actually shocking to see snapshots of the author playing with his grandkids.

No one wants to be a phony—an absolute in Salinger’s universe. But one reason teenagers love Salinger more than adults is his simplistic morality. Writers have to write, but they also have to perform, and whether that’s being phony or not has nothing to do with paying the rent. Helen DeWitt tweets! So do Nicholson Baker, Colson Whitehead, and Margaret Atwood. Michael Chabon won the Pulitzer Prize but he still Instagrams his dog. Maybe writers who do this want to sell books (who doesn’t want to sell books?) or maybe they believe their thoughts on Brexit are worth sharing or maybe they think their dog is cute or maybe they just want to feel less alone as they squirm over their keyboards. Maybe if Salinger had a healthier relationship to all the business of being a writer he’d have actually written more.

No doubt social media in particular seems to represent the triumph of the writerly type over the writing itself. But DeWitt, Baker, Whitehead, and Atwood are among our most accomplished writers; so what if they’re willing to play the type on occasion? It might seem possible to just perform the office of writer—thoughtfully curated Instagrams of to-read piles, tweets geo-tagged at the MacDowell Colony—but it’s still a publish-or-perish business.

Salinger beat the game. Declining to perform allowed him to never again have to publish, and instead of perishing his work thrived. At least, the work we know. It’s said there’s more, and that someday it will be published. I have my doubts, and anyway, it will be impossible for that work to get a fair reception. The shadow of Salinger as hermit will forever obscure whatever he was up to in his many years of public silence.

Salinger thought he had attained artistic freedom, and perhaps he did, but it will cost him something nonetheless. This exhibition, organized by his son, Matt, and widow, Colleen, explicitly aims to fill in the gaps the writer so long declined to. Perhaps by giving us what we most want to see—the man—we’ll eventually get back to the work. It’s a course correction, maybe too little, certainly too late.

Did you know that Salinger himself designed the little bars of color that decorate his all-white book jackets, specifying they should be green atop orange atop blue atop purple atop black atop brown atop yellow? I did not. It’s an interesting tidbit but only a tidbit. Looking at Salinger’s stuff, it seemed so sad that this was what he was keeping from us—that he was as human as we are.