Intermittently, Americans are beginning to get upset that their government is locking tens of thousands of human beings in camps. At present, more than 50,000 people suspected of having entered the United States without proper documents are being held in “immigration detention facilities,” more accurately described as concentration camps. More than half of the camps are run by for-profit corporations. Malnutrition, filth, physical and sexual abuse, and the denial of medical care are rampant: The Intercept recently recounted the story of one man who committed suicide while in solitary confinement, after begging just to be deported to Mexico so that his incarceration could end.

But most Americans are only paying attention some of the time. Headlines and protests spiked in the spring of 2018, when the Trump administration declared family separation (euphemistically termed “Zero Tolerance”) to be government policy across the entire U.S.-Mexican border; the outcry was so explosive that on June 20, 2018, Donald Trump was forced to sign an executive order, ostensibly ending family separations at the border. In the aftermath, the furor died down, and much of the press moved on. The historian Mara Keire has been recording on her Twitter account how many articles The New York Times and The Washington Post run each day on the concentration camps: Nowadays, the number is often zero.

Yet even as the protests and the outcries wax and wane, the U.S. government continues to separate families. “It’s not on the scale of what we saw during Zero Tolerance, but it’s still an incredibly troubling and very large number,” legal advocate Christie Turner-Herbas told Time in September. In fact, advocates had to fight the Trump administration in court to ensure that imprisoned migrant children had access to such necessities as soap, toothbrushes, and mats to sleep on. The administration is currently engaged in a legal battle to be able to imprison migrant children separately from their parents for even longer periods of time.

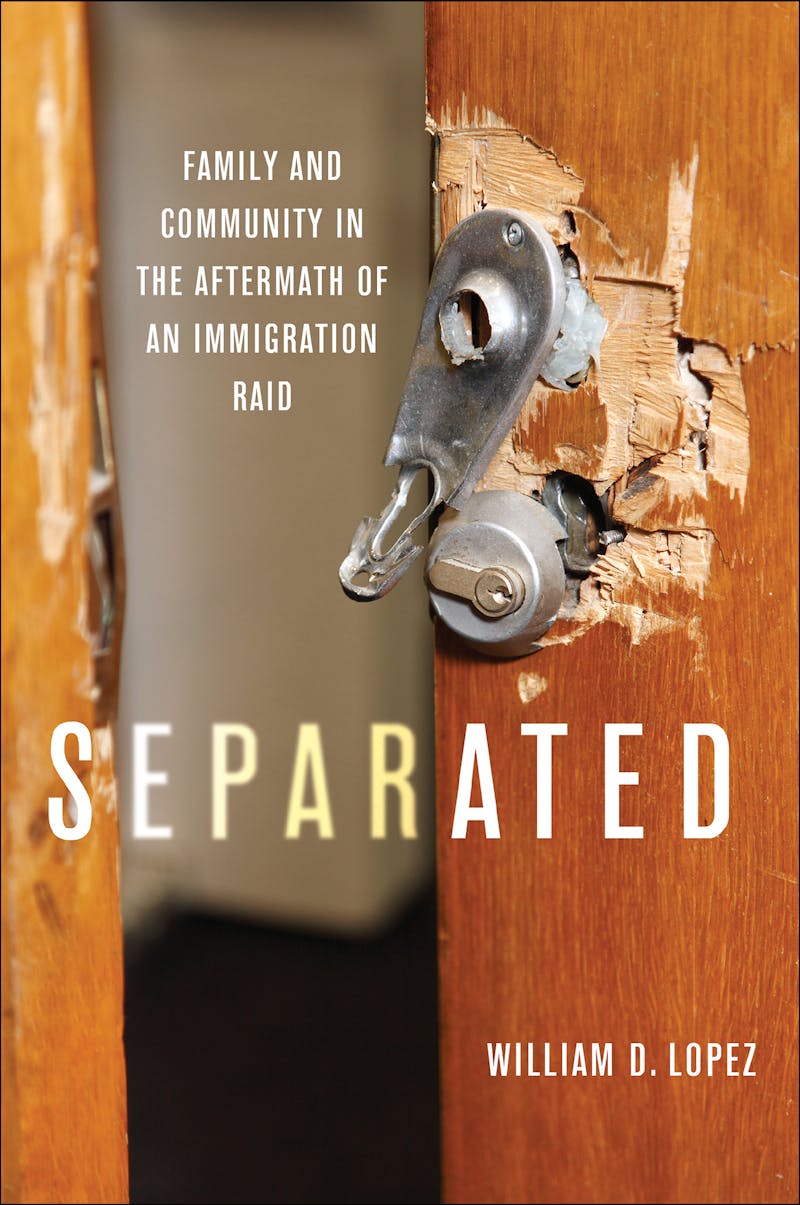

This system is hell. But it is not the particular hell described by William D. Lopez in his remarkable new book, Separated: Family and Community in the Aftermath of an Immigration Raid. Instead, Lopez, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, writes about what happens to predominantly Latino communities after an immigration raid. His book is about the cost of the enforcement of the U.S. immigration system for those who are left behind—for those who are, in a very real way, still being hunted by men with guns (police and federal agents). And it is a devastating story.

Separated examines the aftereffects of one particular immigration raid that took place in Washtenaw County, Michigan. It was there, on a cold November morning, that Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers pulled out their guns and detained two Latino men, Santiago and Julio, who were on their way to buy milk. For some reason, ICE suspected that Santiago, originally from Mexico, was selling drugs out of his auto garage, or taller. (He was not.) But between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. that day, at least four other Latino men were arrested as they drove away from Santiago’s taller. “Word spreads in the community of anti-Latino enforcement,” Lopez writes. “Huron Avenue has been marked: if you are Latino, stay away.”

At about 6 p.m., local SWAT officers raided Santiago’s taller and his apartment, which was just above the taller. Six white men in helmets and vests kicked in the door to the apartment, breaking the lock, and forced the nine people present within into the living room. There was Santiago’s undocumented 18-year-old son, Santiagito; Santiagito’s white, U.S.-citizen girlfriend, Jessica; Jessica’s U.S.-citizen mother, Diane; Santiago’s undocumented wife, Fernanda; her two U.S.-citizen children, Lena and Ignacio; Santiago’s undocumented sister, Guadalupe; her two U.S.-citizen children, Sofía and Fatima; and a friend, Sergio, a legal permanent resident. Guadalupe’s husband, Antonio, had been one of the Latino men arrested by ICE agents earlier that day.

Because of the flash-bang grenades the SWAT officers threw, Fernanda and her daughters had trouble breathing. According to Jessica, the SWAT officers held their guns to people’s heads and yelled, “If you are here you need to speak English. Why are you going to come here if you are going to speak your fucking language?” ICE agents arrived, and together the law enforcement officers dumped out drawers, scattered papers, and threw clothes across the floor; their drug dogs dripped mucus all over the residents’ belongings. Three representatives from Washtenaw Interfaith Coalition for Immigrant Rights (WICR, pronounced “wicker”) arrived at the apartment and began to take notes. After learning that Santiagito was 18, an ICE agent slapped cuffs on him and began to lead him to the van outside. “Jessica slips her phone number and address in Santiagito’s pocket,” Lopez writes. “Maybe he can call her from the immigration office. Or Mexico.”

In the wake of this raid, poverty, precarity, and pain follow. Lopez writes of two forms of violence against communities of immigrants and their families: One form is “the acute trauma of arrest and deportation,” but a second form, a slower and more chronic form of violence, is the “suffering engendered by a loved one’s haunting absence and the emotional and economic impacts it causes.”

With Santiago gone, his wife, Fernanda; sister, Guadalupe; and each of their children were suddenly thrown into financial devastation. Santiago had been their primary source of income, but now he was gone. Worse, they now needed to raise thousands of dollars to support Santiago’s defense. Hilda, the wife of Arturo, another man arrested in the raid, had to find $10,000 in just four days. Frida, the girlfriend of another man arrested driving away from Santiago’s taller, was never able to pick up his car, which was then impounded.

Because the SWAT officers had broken the lock to Santiago’s family’s apartment door, the apartment was “ransacked” the next day when Guadalupe and Fernanda left to get diapers. Their landlord had decided to kick them out. And, because Santiago supposedly owed him rent, the landlord entered the apartment and confiscated clothing, furniture, money, electronics, and the tools upon which Santiago had relied to make his living. Only after calling the police—a very dangerous move for undocumented people—could Guadalupe and Fernanda retrieve two mattresses and some clothing.

Many of those whose family or friends were taken in the raid were afraid to leave their homes in its aftermath. They altered their day-to-day routines, resulting in isolation. “We didn’t know if [law enforcement] was finished or if they were still detaining people,” recalled Guadalupe. This limited their ability to obtain much-needed food and social services. Further, the families affected by the raid were stigmatized. Many in their community were now scared to be around them. As one outreach worker described it, “this family was marked.” It’s not uncommon for such families to have to relocate entirely.

Many in mixed-status communities are especially afraid to drive their cars in the raid’s aftermath. As Lopez describes in painful, painstaking detail, simply driving is a fraught activity for anyone with dark skin, but especially for those who are undocumented. Following September 11, most states (including Michigan) made it considerably more difficult for undocumented immigrants to drive legally; in most states, undocumented immigrants can no longer obtain a U.S. driver’s license. And while in many states individuals can drive legally with a driver’s license issued by another country, they often must have an English translation of their foreign driver’s license, and some local law enforcement departments have their own additional standards with respect to foreign licenses. Further, local police often don’t know that foreign licenses are allowed.

Thus, for undocumented immigrants, driving to the store to get some milk or diapers is an extremely perilous act. Because of this, the life of an undocumented person who needs to drive for work or family or pleasure is “filled with close calls and near-deportations: with deportations that almost were, could have been, and just might be next time.” As Lopez documents, law enforcement officials often target everyone who looks Latino, meaning that these people exist in a constant and paralyzing state of surveillance and fear.

And then there are the health problems. In the raid’s immediate aftermath, the children were frozen with trauma—which, according to research cited by Lopez, put them at higher risk for all manner of poor health outcomes. The children began to get sick “all the time.” Even years later, Fernanda’s daughter, Lena, would burst into tears every time she saw police. “She thinks they will attack her, like when they came to our house and pointed guns at our faces,” said Fernanda. After being deported to Mexico, Santiago lost weight because of “the nerves.” Some individuals who remained behind displayed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Others considered suicide. Two years later, Fernanda still had nightmares. She had trouble producing milk for her infant son, Ignacio. And the possible longer-term results of this trauma—increased risk of hypertension, detrimental employment outcomes, diminished relationship satisfaction—are bleak indeed.

In addition, “trauma, sick children, and removed caregivers exacerbated one another.” Lopez points to Fernanda, who was forced to deal with her own frustrations and suicidal ideations even as she battled homelessness, joblessness, and her husband’s impending deportation. Further compounding these tremendous challenges was the constant need to secure childcare, but this was made more difficult by the stress of their situation, which caused her children to become unpredictably physically ill.

Ultimately, Santiago, Julio, and Santiagito were deported to Mexico. Barely two weeks later, Fernanda took a bus with her children to Texas and then walked across the border into Mexico. Guadalupe, Hilda, and others managed to eke out existences in the United States. Lopez writes that he was unable to determine what happened to some of the other men detained in the raid.

A specter hangs over Separate like an evil, orange cloud: Donald Trump. It is Trump, after all, who constructed his entire political career on demonizing Mexicans and others with dark skin. It is Trump who gleefully ordered that the “Zero Tolerance” family separation policy be expanded to cover the entire southern border. Yet Lopez doesn’t mention Trump’s name until the book’s conclusion. This is largely because the raid at the heart of Lopez’s book took place in 2013, during the presidency of Barack Obama.

Herein lies one of the most important—if dispiriting—takeaways from Separated. The brutality of the American immigration system is bipartisan. Democrats, as well as Republicans, are complicit. To date, the Trump administration has actually deported fewer people than did the Obama administration over the same period of time. During the course of his presidency, Obama deported well over two million people, leading immigrants’ rights groups to label him “deporter-in-chief.” By 2012, these deportations had separated some 150,000 U.S. citizen children from their parents. During the Obama presidency, men, women, and children were held in freezing cells, without showers, toothbrushes, sanitary napkins, or toilet paper. During the Obama presidency, sexual and physical abuse were common in immigration detention facilities.

Indeed, the so-called “287(g) agreements,” which allow local law enforcement officials to enforce aspects of federal immigration law, were an Obama-era innovation. And it is these agreements that enable the panoptic surveillance system described by Lopez. It’s significant that the agents who burst into Santiago’s apartment, guns raised, were not ICE but rather local SWAT officers. “Unlike southern border states such as Texas, Arizona, and California,” Lopez writes, “much of the interior of the United States is not patrolled by la migra.” The immigrants who live near him in Michigan live less in fear of ICE or Border Patrol than of local police.

Because so much of the surveillance and detention is undertaken by local police, Lopez investigates the attitudes of these police, interviewing many and participating in several ride-alongs. “What I learned was simple,” he writes: “Black men are violently killed in much the same way that brown men are violently detained and deported.” Both the war on drugs and the war on the undocumented have cast “men of color as dangerous villains who prey on innocent community members.” The same police who may shoot an unarmed black person one day may also detain a brown person and hand him over to ICE the next.

Lopez concludes Separated with a call for: “Black and Brown Unity Against State Violence.” Both Latinos and African Americans, he writes, are disproportionately surveilled, detained, and killed by law enforcement officials; this surveillance, in turn, represents just one manifestation of broader systems of oppression. The oppression faced by different groups is different, to be sure, but this makes it all the more vital for, say, citizens to advocate for noncitizens, and for light-skinned individuals to protest police violence in ways that would place dark-skinned individuals at mortal risk. White U.S. citizens must reflect on their own “casual acceptance of extreme violence meted out on Black and brown community members.” The recent spate of protests at ICE facilities is encouraging, but—with concentration camps up and running—it is far from enough.

Lopez admits that he wrote the book to imbue readers with “a deep sense of brutality” in the current U.S. immigration system, to enable them to think about the effects of that system in a broader way, and to give a voice to those who are usually ignored or silenced. “I write this book from a position of vulnerability, as an over-educated researcher, a citizen, and a man, who dares to speak about the lives of undocumented Latina women who give their bodies to physical labor, cleaning the very hotels I sleep in when I talk about their suffering at academic conferences,” he writes. “I speak on behalf of Guadalupe, Fernanda, and Hilda because society has chosen not to listen to undocumented Spanish-speaking Latina mothers when they speak for themselves. When society decides it is finally time to hear them, I will promptly be silent.” Until that time, Lopez’s book is one of the most powerful examples to date of an academic using deep study and radical empathy to indict a profoundly evil system.