Another year, another stream of sensationalist headlines out of Mexico: drug violence, femicide, the ongoing migrant crisis, and an economy that continues to fall short of its potential. All these problems existed before Mexico’s new president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, took office last December. Yet in the past year, it has become increasingly clear that López, better known as AMLO, poses a genuine threat both to Mexican prosperity and democracy, his actions while governing bearing little resemblance to the progressive banner under which he ran.

Like many populists—from Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro to Donald Trump himself—AMLO is a politician without any fixed ideology who nevertheless inspires cultlike devotion in his followers. Mexico would likely profit from a genuinely progressive, democratic governing party and president. Instead, an authoritarian figure promising easy, short-term solutions to immensely complex challenges is working to dismantle the substantial progress the country has already made.

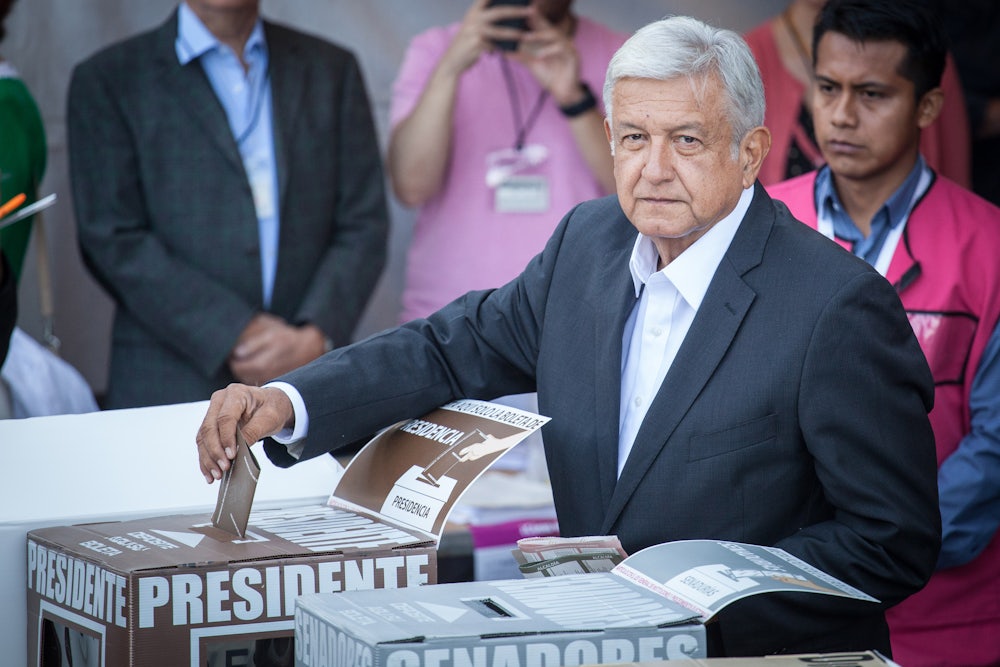

AMLO was elected in July 2018 amid a wave of dissatisfaction with the weak and ineffective center-right and left governments that had governed since Mexico’s 71-year Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) regime voluntarily ceded power in 2000. The intervening period has seen positive advances: free elections, the building of independent institutions, and the diversification of the economy away from oil and agriculture toward tech and manufacturing. Yet the shift has left many behind: Mexico remains a country where over 40 percent of the population live in poverty, and political power brokers and other vested interests remain untouchable by the law. 2019 is estimated to have seen a record number of homicides.

On the campaign trail in 2018, AMLO promised Mexicans a “Fourth Transformation”—following Mexican Independence, the separation of church and state, and its 1910 Revolution—yet his actual policy positions were vague. He would reduce social inequality by “ending privileges”; corruption would be “eradicated”; the country’s deadly drug war would be “over.” Such rhetoric played well in a country where the intricacies of representative democracy, hamstrung by weak leadership and dysfunctional institutions, have left citizens disillusioned. A 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center found that only 6 percent of Mexicans were satisfied with their democracy and only 17 percent claimed any confidence in the graft-plagued administration of Enrique Peña Nieto that preceded AMLO.

Yet the first year of AMLO’s term unfolded quite differently than his supporters on the progressive and center-left, both in Mexico and the United States, had hoped. From a Donald Trump–backed crackdown on migration—over 29,000 undocumented migrants were detained by Mexican authorities in June alone, a 204 percent increase over the same month the previous year—to AMLO’s ambiguous views on abortion, same-sex marriage, and drug reform, there is little of U.S.-style progressivism in his administration.

AMLO speaks simplistically about morality and the “conservatives” and “neoliberals” he claims seek to destroy Mexico and bring down his presidency. Yet the coalition led by his party, the National Regeneration Movement (Morena), is a rogues’ gallery of opportunists that includes Christian evangelicals, multibillionaire business allies, and proud sympathizers of the Chavista regime in Venezuela. When confronted with evidence that contradicts his own in his now-famous daily 7 a.m. press conferences, AMLO admonishes journalists for conspiring against him and boasts of his otros datos—strikingly similar to the Trump administration’s “alternative facts.”

While he publicly rails against neoliberalism, AMLO is no far-leftist: His government has successfully renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement—now to be known as the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement—with its northern neighbors; he is openly courting private-sector allies at home. Yet his obsession with reviving Mexico’s state energy giant, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), and his almost complete ignorance of public finances are deeply concerning. While Pemex’s revenues fueled much of the country’s twentieth-century development, it’s currently the most indebted oil company in the world, faced with rapidly depleting reserves and plummeting production.

Mexico should be looking toward economic diversification and tax reform. AMLO has done the opposite—slashing the budgets of a variety of important institutions, from the ministries of Health and Education to criminal justice agencies, to finance an $8 billion refinery in Veracruz State, ostensibly to wean Mexico off foreign energy imports, even as its existing refineries operate at barely 40 percent of their capacity. Regardless of which side of the ideological divide one stands on, the project is financially unviable.

Mexico needs to invest more in its economy and people—particularly its most vulnerable citizens—yet the country’s federal and state governments have little ability to do so. In 2018, the country brought in just 16.1 percent of its GDP in government income. Fifty-six percent of the Mexican labor force works informally in sectors that go untaxed; a recent report by the McKinsey Institute highlighted Mexico’s two “missing middles”—midsize companies that could create better-paying jobs and encourage a more competitive business environment, and a prosperous middle class whose spending and saving could fuel domestic demand and investment, as well as contribute to public coffers.

Notably, the only states in Mexico to boast significant growth in the past 20 years lie in its industrialized north, where a combination of foreign direct investment and public initiatives (education, training, tax incentives) have driven diversification, innovation, rising education levels, and job creation. The country’s mostly rural south—undereducated, beset by vote-buying and clientelism, isolated from the global supply chain—remains impoverished.

For now, Mexico’s economic outlook is bleak. With further declines in oil production expected, Fitch Ratings downgraded Pemex’s credit rating to junk status in June, while the cancellation of a major international airport project following a hastily arranged popular referendum by AMLO in 2018 has already affected private investment. In the first half of 2019, the country entered a light recession, which could easily worsen.

If AMLO’s economic project is a fairy-tale, his political vision is disturbing, particularly given the long and painful history of authoritarianism in Mexico and Latin America as a whole. AMLO has attacked democratic institutions for years from the sidelines of power, accusing them of bias toward Mexico’s elite and of thwarting his previous bids to win the presidency. Now, with Morena controlling both houses of Congress and a majority of state legislatures, he is going about reshaping them as he wishes. Even many former supporters have criticized his blatantly authoritarian moves to install party loyalists in positions within key institutions, such as the Supreme Court and the National Human Rights Commission. Yet most worrying of all are his attempts to influence the National Electoral Institute (INE), the autonomous body responsible for organizing and overseeing elections in Mexico at all levels of government, as well as allocating campaign funding to political parties.

Along with drastically reducing the budget of the institute, a new bill proposed by the Morena party would have Mexico’s lower house select a new president of the INE every three years, instead of the current nine. While billed as a reform, the change would potentially allow for the current Morena-controlled Congress to select a new INE president in time for the next election. AMLO would need the support of other parties to secure the necessary two-thirds majority to implement the reform. But if his bill succeeds, the INE would effectively become a means for him to manipulate the outcome of future elections—beginning with midterms in 2021. Critics also fear a 2022 recall referendum—which AMLO himself proposed in order to give voters an option to vote him out halfway through his term—could be used to soften the ground for eventually ignoring the constitution’s one-term limit.

Mexican democracy will likely face its toughest challenge in the coming decade. Surveys show public faith in institutions is extremely low. Mexico’s opposition parties are weak, divided, and lacking in clear policy alternatives.

The entire world appears to be passing through a period of dissatisfaction with the political status quo. Yet as Steven Levitsky, political scientist and co-author of the influential How Democracies Die, said in an interview in Mexico in November, while a country like the U.S. possesses democratic traditions and institutions that help resist the populist impulses of a Donald Trump, nations such as Turkey, Hungary, and Mexico (whose current two-decade democratic experiment is the most significant in its history) are far more vulnerable to demagoguery.

It is worth pointing out that much of what is currently unfolding in Mexico was predicted. AMLO has outlined his policy aims and political beliefs for years in prior, unsuccessful presidential campaigns. And still, much like Hugo Chávez and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, he was broadly supported by left-leaning and even moderate public commentators in Mexico and abroad—quite a few of whom, just a year into his term, are backpedaling on the views they expressed before the election.

Latin American leftists, and their many supporters in academia and the media abroad, urgently need to explore why this keeps happening and what policy proposals and values progressives in the region stand for in the twenty-first century. Opportunist populism is not a coherent ideology.