One of the principal thrills of The Lives of Lucian Freud: The Restless Years, 1922-1968 is that we are in the capable hands of William Feaver, The Observer’s longtime chief art critic. Here’s how he writes about the 1945 painting Dead Heron:

Powder paint from the barge shop in the Harrow Road, mixed with oil or water, was closer to Renaissance practice than paint squeezed from tubes. The bedraggled heron is a legless device lopped from an Uccello helmet, cruciform on damp sand, graced with enamel shine. Neither commemorative nor symbolic, more magnificence brought low, it reminded Freud of the stuffed gull that had served as his albatross when he was the Young Mariner with the Dartington Eurythmic Players.

This passage illuminates the artist’s style (his preference for industrial paint) and the writer’s—the summoning of pigment “squeezed from tubes” to conjure the “bedraggled” bird, a “magnificence brought low.” That throwaway reference to Uccello attests to Feaver’s educated eye: damned if the thing doesn’t look like frippery on the heads of the combatants in “The Battle of San Romano.” The book is so comprehensive that we even understand the reference to the stuffed bird—a hundred pages earlier, there is a photograph of the 12-year-old Freud in that very production.

Feaver is a brilliant docent, but Freud is the ultimate authority on himself. Vis-à-vis Dead Heron: “I always had a horror of using materials that reminded me of art schools, and that’s why I used Ripolin,” which was formulated for boats and industrial uses. “I didn’t like the idea of the awful Winsor & Newton ready-made kit because I thought that tainted the idea of doing anything.”

Freud butts in throughout this book, to give context to his work, his relationships, his development. He had, it would seem, an incredible memory: He was in his early twenties when he painted Dead Heron. It’s not an especially interesting or important part of his oeuvre, so why talk about it? Biographer and subject talked about everything. Feaver initially intended “a brief account of Freud the artist,” but as the man’s friend and collaborator (he curated multiple exhibitions of Freud’s work), he had incredible access, including almost daily telephone calls.

What I’m trying to say is this biography is authoritative and exhaustive. Happy accident that it’s so lovely to read.

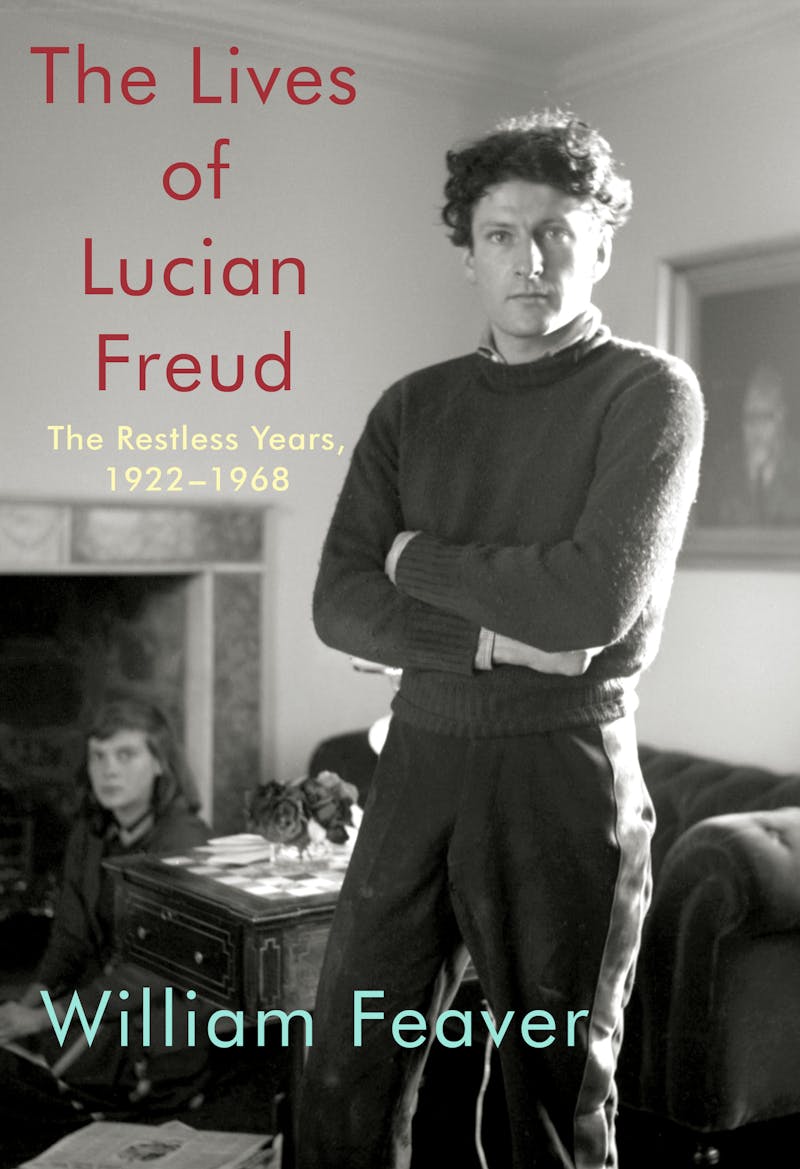

There’s name-dropping because Freud was a society man (Sigmund was his granddad) and gossip because Freud slept with seemingly every woman in his orbit. This makes a lot of sense; the man was gorgeous. If that never complicated Freud’s career, it may color his legacy. Last year the artist Celia Paul published a memoir detailing her relationship with the much older Freud, who died in 2011. This volume only covers half his life; a second volume, Fame, will be published later this year, and it may well provide an alternative view of his relationship with Paul.

For the most part, what Feaver documents adheres to what Rachel Cusk, in a profile of Paul, theorizes as the archetype of the male artist:

He is violent and selfish. He neglects or betrays his friends and family. He smokes, drinks, scandalizes, indulges his lusts and in every way bites the hand that feeds him, all to be unmasked at the end as a peerless genius.

It’s useful to keep this in mind. While it’s a boon to future academics that Feaver has so thoroughly documented Freud’s every move, it’s up to readers to interrogate why bad behavior is the remit of masculine genius—to look at Freud as closely as he did the subjects of his portraits.

Among those subjects was, of course, himself. Lucian Freud: The Self Portraits recently closed at London’s Royal Academy of Arts; a selection of more than 50 paintings, drawings, and etchings, it’ll travel to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in March. Those of us unable to visit in person at least have a documentary of the same name, produced by Exhibition on Screen, which specializes in bringing these sorts of blockbuster shows to cineplex audiences.

It’s a tease to read an artist’s biography. You always want to see the work being discussed, and while Feaver’s book is nicely illustrated, there’s much, by necessity, left out. While no film can match the experience of visiting an exhibition, that is not the aim of Self Portraits, really. Instead, it conjures what it’s like to take one of those audio tours at a museum.

There are a host of experts chatting at us about Freud, and archival interviews with the artist himself (I loved his arch, plummy accent), and it’s a pretty good crash course on his place in art history. James Hall, author of a book on the self-portrait as a form, notes Freud’s kinship with Rembrandt, whom he describes as the first artist to become famous for what he looks like. And you do see, in Freud’s unsparing nude study of himself at age 70 (still quite handsome!), a kind of synthesis of how Rembrandt rendered himself over the years: mischievous, serious, sedate, triumphant.

When I visit museums, I rarely listen to the guided tours and often try to look at the work before I read any explanatory wall text. I want to make up my own mind, or at least let my eye have first crack at things. The film cannot approximate this particular process, but the camera does linger long enough on the works under discussion that you can see what the experts are talking about. When they describe a small 1963 self-portrait as almost a finger painting, reflecting the artist’s interest in sculpture, the camera lets you see how the thick pigment does indeed create an almost three-dimensional effect.

There are intriguing discussions of some of the artist’s most startling work: 1978’s tiny but potent Self Portrait With Black Eye (Freud’s interest was in showing people not at their best but as they were); the confounding Interior With Plant, Reflection Listening, in which the artist’s body is obscured by a massive houseplant; and 1965’s extraordinary Reflection With Two Children, in which the artist looms large over his progeny. One wonders what Grandfather Sigmund would have made of all this.

The film closes with the remarkable assertion, by the art historian Tim Marlow, that Freud is “one of the great European painters of the last 500 years.” Another of the film’s experts puts Freud in the company of Dürer, Cranach, Holbein, Rembrandt, and Titian. No pressure. Among the works in Self Portraits are paintings of other subjects, with the artist present in shadow or a glimmer of reflection inside the frame, like Van Eyck in the convex mirror. I don’t know if Freud will be remembered for another half-millennium, but it seems clear he did not want to be forgotten.