The Bauhaus, open for less than a decade and a half, was one

of those rare influential failures. It was like the Velvet Underground, the

band that inspired all of its fans to start bands of their own. The art

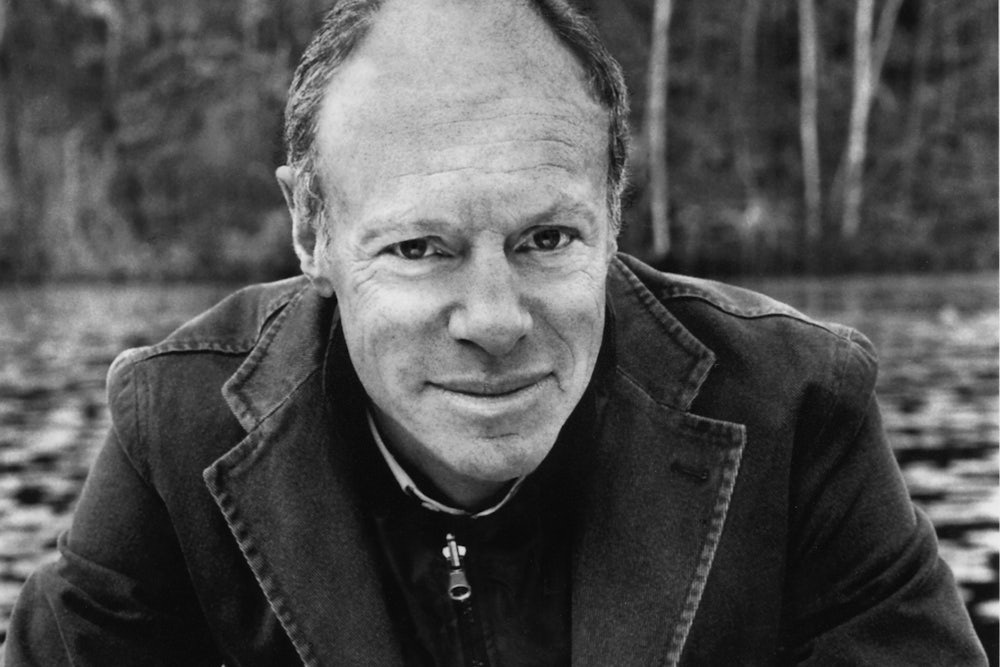

historian Nicholas Fox Weber—the author of The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of Modernism and the executive director of the Josef and

Anni Albers Foundation—goes even further. The title for his new book, iBauhaus: The iPhone as the Embodiment of

Bauhaus Ideals and Design, gives away its conceit, suggesting that it’s time we

looked more closely at those machines we carry around all day.

Weber offers a crash course in the Bauhaus itself. Founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius, it was “a groundbreaking school and laboratory for modernism,” Weber writes, promulgating design that offered both ease and beauty. The institution’s belief in mass production helped spread its philosophy, which got bound up in modernism more generally. We continue to judge design’s efficacy against the standards Bauhaus helped establish.

Weber isn’t actually arguing that the iPhone is a work of art. “The Bauhaus was a colony of artistic geniuses,” he writes. “Several individuals of unparalleled imagination and poetry were succored there. Nothing about the iPhone rivals their achievement.” Still, it’s not a stretch to argue the latter is designed to “ameliorate daily existence,” as Weber argues, and to do so with the charm of its own “aesthetic grace.”

The function of all criticism is persuasion, and you will either be seduced by Weber’s command of the material or irritated at the way he gets carried away. For example, the Bauhaus system contained something termed the foundation year. Josef Albers taught the course and proselytized for it thereafter at Black Mountain College and the Yale School of Design. In short, students would spend time starting from scratch. They’d take single sheets of paper and fold them in complex ways, trying to master the possibilities of form. What if you knew that British design education also relied on this kind of exercise, and such training formed the foundational education of the man responsible for the iPhone’s design, Jony Ive?

Weber is full of such details; he often resembles a conspiracy theorist with a coincidence. In 1921, Herbert Bayer was a student at the Bauhaus. He eventually settled in the United States, where he designed the headquarters for the Aspen Institute. In 1983, Steve Jobs spoke at the Aspen Institute, outlining his vision of the computer as a tool for all. “Like Gropius, he was not interested in products for the elite few, but in what could benefit the world at large,” Weber says.

Weber also sees traces of Bauhaus in Apple’s institutional ethos, including its rejection of internecine competitiveness in favor of communal meals and an emphasis on shared objectives. He even notes a similarity between the two institutions’ names:

“Bauhaus” also was slightly ambiguous. “iPhone” would be the same: concise, previously nonexistent, snappy, and provocatively inexplicable.… The lowercase i before the uppercase “P” is startling. The meaning of the i is elusive. These names put us in a position of questioning; at the same time, they humor us with their punch and rhythm.

Such is Weber’s argument: persuasive if you’re in the mood to be persuaded, preposterous otherwise. He makes something out of Ive’s desire that the iPhone’s display be “magical,” remarking that this is the very word Albers used to describe the interactions of color and the use of line to conjure impossible form (the thinking writ in his seminal studies of the square paintings). Is it a reach? What about when Weber notes that both Albers changed their names—swapping the ph in Joseph for an f, cropping the end of Annelise to become just Anni—then argues that Steve Jobs’s surname sounds invented, though there’s no evidence it was?

I find the author’s mania almost charming and was thrilled by his most audacious theories.

The white that is the background of computer screens, iPhones among them, functions like the white of a clean piece of typing paper, or of the “supports”—to use the correct art-historical term—of the paintings Klee and Kandinsky and Schlemmer made at the Bauhaus. Whether they were working on paper or canvas, white was necessary not just as the recipient of and most useful background for color, but also because of the way it is a start. And most importantly, it is otherworldly.

This is in stark contrast to how Weber feels about the iPhone’s packaging!

All those pieces of shiny white cardboard give the impression that they are flawless and can be disassembled and reassembled with the flick of a wrist, but when you open the boxes you feel inadequate because you cannot get to their contents without destroying its impeccable elements.

Yes … been there. When Weber points out that Steve Jobs was raised in one of the tract homes developed by Joseph Eichler, I see his point. Here’s how Jobs explained it to his biographer, Walter Isaacson: “Eichler did a great thing. His houses were smart and cheap and good. They brought clean design and simple taste to lower-income people.” I wish Weber hadn’t gone on to contrast Eichler’s project with that of another midcentury real estate developer, one whose son now occupies the Oval Office. But this is what we should demand of our critics, that they look deeply, with a single-minded focus. Like most of us, I’ve looked at my iPhone countless times; having read this book, I now feel I’ve truly seen the thing.