Joe Biden’s history of hesitating to run for president—he contemplated runs in 1984, 1988, 2008, and 2016—is often ascribed to his sense of responsibility. Recounting how Biden finally backed himself into his first presidential run in 1988, Jules Witcover, the author of the 2010 biography Joe Biden: A Life of Trial and Redemption, runs through a litany of worries that Biden considered: How would the presidential spotlight affect his children? Would it leave him enough time to maintain his Senate committee workload during the campaign? He’s portrayed as a statesman sizing up his duty, as numerous reporters also described him as he mulled his delayed entry into the 2020 race.

There’s another—more colorful and revealing—angle to Biden’s foot-dragging in 1987. As recounted in Richard Ben Cramer’s classic on the 1988 presidential election, What It Takes, the run-up to the 1988 primary was marked by intense, even desperate attempts to justify a Biden candidacy. Biden huddled with a small team of “gurus,” including his longtime friend Pat Caddell, searching for a political brand to encapsulate the magic his unwieldy stem-winders worked on Democratic donors and party groups. “Everybody in the country who could read knew that Biden wanted to run,” Cramer writes, “but he wasn’t going to run without message … and he didn’t have a message … nothing to say.” Caddell tried to impose a message of generational change, of boomer reawakening, complete with pop-culture references unfamiliar to the buttoned-up potential candidate. Biden tore Caddell’s speeches to shreds, adding pages of his own just hours before he was to appear at the 1987 California Democratic Convention in Sacramento. The highlights he would read to his wife Jill over the phone, ecstatic, were actually passages by Robert F. Kennedy that had sifted into Biden’s words amid the chaos, and would spark a plagiarism scandal.

In his 2007 memoir, Promises to Keep, Biden describes these early branding struggles as an earnest effort to distill the truth about himself as a politician and to satisfy a press he had never had time to be chummy with. “I still felt like my message was a bit opaque, like audiences were hearing me through a veil.” Journalists widely noted that, as one Los Angeles Times reporter put it, Biden “sells the sizzle but is short on the steak.” But Biden, like his gurus, knew he had the only thing that mattered: “I’m a gut politician; I know when I leave a room whether I’ve connected or not, and there just weren’t that many misses when I started out. I started to feel that as long as I showed who I was and what I held most dear, I’d do okay.” Biden’s campaigning depended on bouts of frenetic, lightning-in-a-bottle momentum as he pushed audiences to make “the connect,” sometimes to the disbelieving awe of his advisers. In private, they chided him about the participation in civil rights marches and protests he was inventing on the stump, but to no avail. The boomer crowds Biden would later describe as “hungry” ate from his hand; as Cramer writes, “They loved how Joey made them feel.”

By 2020, Biden’s 1988 flameout had morphed into the ill-fated middle act in an arc of rise, fall, and rise. Shaped in part by Biden’s memoir and Witcover’s biography, and helped along by his elder statesman role as Obama’s vice president, a compelling narrative took hold. This Biden Story was one of outsize ambition tempered by unusual personal tragedy and unshakeable family values, showcasing the redemptive power of resilience and—a word that Biden and his allies often deploy—“integrity.” Middle-class Joe, doggedly boarding Amtrak to Delaware to tuck in his children at night, shrugging off the Washington club and the press, always going the extra mile with voters. Joe Biden always “getting up” again, as his father taught him, always believing “politics was a matter of personal honor.” This may have been the essence, the message, that he was lacking in those harried brainstorm sessions in 1987.

But that version of Biden is only convincing if you abstract the man from the substance of the politics he lived through and shaped. What do terms like “honor” and “integrity” really mean in the context of a decades-long career intertwined with the collapse of the United States into plutocracy led by an authoritarian television personality? Which Biden matters: the handsome golden boy, the working-class Kennedy figure, championing integrity and honesty—or Biden the politician, playing both sides of a widening political chasm, advancing in practice the developments he deplored in the insulated realm of rhetoric?

“Joe Biden is not a bad or evil man,” Branko Marcetic writes at the beginning of his new book on Biden, Yesterday’s Man, the only work to date that examines the patterns and broader historical consequences of Biden’s record. “But he is someone who, by virtue of the political, social, and historical forces that shaped his life, made choices and drew political lessons that not only make him ill-suited to combat Trumpism but led him to help engineer the very conditions that handed Trump victory in the first place.” By restoring the dimension most conspicuously absent from the going Biden Story—the impact of his politics—Marcetic illuminates how Biden the man, the hotshot political dreamer with a thin, moralistic conception of public service, was an ideal face for the Democratic Party’s reorientation toward a wealthier voting base and its alignment with corporate interests.

The written record yields no evidence of Biden ever having had an ideology in the sense of a coherent, historically grounded political worldview. In Biden’s own telling, politics as packaging and profession appealed to him from a very young age; inspired by John F. Kennedy as the first Catholic president, the young Biden famously looked up politicians’ biographies to find out how they got where they were. Though he’s known to cite poets, it’s hard to think of an example of Biden invoking works of history or political ideas that shaped his thinking. His liberalism seems to have been inspired, indirectly, by the Catholic milieu of his early life and his parents’ aversion to the abuse of the weak by the strong. Biden has always manifested an aversion to racism to the extent he saw and understood it, though he would soon begin taking it upon himself to tell “interest groups” what they really needed from his own position on the inside track.

Marcetic notes a pattern, starting with Biden’s first attempts at elected office in the early 1970s, and growing more prominent and spectacular as Biden began to win senate reelections by large margins and climb the ranks in the chamber. “Whether it has been crime, drugs, terrorism, or something else,” he writes, “Biden has tended to get swept up in every right-wing panic of the last few decades, often going even further than Republicans in his response.” Beginning with his stunning upset election to the Senate in 1973, Biden perfected a strategy of selectively outflanking Republican opponents on the right. The most famous example of this, of course, is also the oldest: Biden’s strident opposition to busing in the 1970s, which found him forming partnerships with Southern segregationists in the Senate and working to shatter the Democratic consensus behind muscular civil rights policy. Biden’s defenders today may argue that his position was necessary for political survival in the face of the angry, mobilized, middle-class electorate that threatened Democratic politicians in those years. Either way, Biden still repeats the myth that busing was a failed policy—a “liberal train wreck,” as he wrote in 2007.

His anti-busing furor was only the beginning. Biden’s maneuvers on the right wing of the possible in Democratic politics may have originated in political opportunism, but they invariably hardened into his most enduring convictions and became the central features of his Senate record. Less than two years after winning his seat, Biden was describing himself as a fiscal conservative and boasting about his willingness to buck liberal orthodoxy and tell hard truths to “special interests”—namely, the Democrats’ core electoral constituencies. Campaign contributions poured in from California businessmen, along with an endorsement from Howard Jarvis, the right-wing mastermind of Proposition 13, the anti-tax measure that has wrecked California’s solvency and ravaged its public services to this day. In just one minor example of Biden using liberal good-government rhetoric to mask his energetic collaboration with anti-government ideologues, he announced in 1978 he was “delighted” with the endorsement at the same time he denounced measures like Prop 13 to African American voters.

“In a strange way,” he said in 1980, “the election of Ronald Reagan is more consistent with the budgetary thrust that a guy like me … has been going for for the past few years.” Biden consistently voted for Reagan’s draconian budgets and tax cuts even as he hammered the president for not going far enough in cutting spending. He was not merely going with the flow, but driving his own party to go further right than the GOP in pursuit of the interests of the “middle class”—a category he and other up-and-coming politicians imagined as affluent, white, anti-government, and the future of a new Democratic coalition.

Nowhere was Biden’s internalization of right-wing politics more evident than in his sensational long-running crusade for a carceral response to drugs and crime. “Just as Biden spent the 1980s chiding Reagan for being insufficiently pitiless on crime,” Marcetic writes, “he would spend the 1990s leading the Democratic Party in an ongoing contest of one-upmanship against the GOP on the issue.” When George H.W. Bush called for $1.5 billion for “more prisons, more jails, more courts, more prosecutors,” which the Heritage Foundation called “the largest increase in resources for law enforcement in the nation’s history,” Biden shot back that the Bush plan was “not tough enough.” He soon boasted that his expanded version of the crime bill mandated the death penalty for more offenses than Bush’s and approvingly quoted a critic who wrote that “Biden has made it a death penalty offense for everything except jaywalking.” A 1991 New Republic editorial remarked that under Biden’s leadership on the Judiciary Committee, the Democrats were “apparently more interested in political one-upmanship than reform,” offering an alternative that was “basically Bush-plus.” Biden would go on to champion the entire infrastructure of mass incarceration, whispering in Clinton’s ear to “up the ante.”

While his current presidential run has forced him to make a hasty retreat from large swaths of his record, on most issues Biden’s thinking has remained remarkably consistent over the years. “Talk of attacking the underlying causes of crime was drowning out something more basic, which was public safety,” he wrote in his 2007 memoir. In 2016, he insisted he was “not at all” ashamed of the 1994 crime bill, adding, “As a matter of fact, I drafted the bill.”

Biden typically represents the substance of his political career—his life’s work of hounding the Democratic Party to outflank the Republicans in their assault on civil rights and the New Deal—in one of two ways. In one telling, it is a product of his deep commitment to the “intellectual consistency and personal principle” of refusing to be defined by ideology or party lines. He made his forthrightness with voters and his fondness for “positions that don’t please anyone” part of his very first Senate campaign, when he told a young crowd that while he was against the Vietnam War, he opposed ending the draft or legalizing marijuana. With Roe v. Wade arriving on the heels of that election, Biden arrived at a compromise position on abortion, which he personally opposed: He thought the “government should be out,” but he would oppose federal funding and “partial-birth” abortion. Given advice by older colleagues to pick a side, the fresh-faced Senator planted his stake in, as he put it, the “middle of the road.” He later reflected proudly that he had “stuck to my middle-of-the-road position on abortion for 30 years,” and considered it a badge of pride to be opposed both by feminists and anti-abortion groups. Biden would only backtrack on federal funding for abortion amid his summer 2019 avalanche of reversals of his lifelong positions.

In another telling, of which Biden is equally fond, his “heterodox” political positions are a product of what Marcetic calls his belief in “consensus and bipartisanship for their own sake,” but could also be described as a mystical attachment to the virtues of splitting the difference. Biden’s writings and speeches are drenched in nostalgia for the bygone era of partisan flexibility that he recalls from his first years in the Senate. As he has written, he believes, deeply and unshakably, that “there is nothing inherently wrong with the system,” that its dysfunctions are the product of personal failures to live up to its genius. The Senate, he wrote in his memoir, was designed to be “a ‘cooling’ institution,” to play an “independent and moderating role”—a “solemn duty that transcends the partisan disputes of any day or any decade.”

Biden has never hesitated to illustrate this betrayed ideal by waxing nostalgic for his relationships with Southern segregationists and white supremacists, whose noxious politics he congratulates himself for having learned to overlook in the face of their individual kindness. In an anecdote he recounts as one of the fundamental lessons of his political life, he was taken to task by a senior colleague for expressing his principled disgust at hearing the reactionary Jesse Helms rail against the Americans With Disabilities Act on the Senate floor. The colleague haughtily informed him that Helms had adopted a needy child, at which point Biden felt foolish and ungenerous for having committed what he now regards as the greatest sin of politics—that of attacking “another man’s motive.”

An even more stunning anecdote has Biden imagining his first desk in the Senate sandwiched between the former desks of the unionist Daniel Webster and the arch-reactionary white supremacist and states-rights ideologue John C. Calhoun. “Standing at that temporary desk,” Biden wrote, “I could place my right hand on what I thought had been Webster’s desk; then I could shift my weight to my left foot and place my left hand on what I thought had been Calhoun’s desk. This was no small metaphor for me and one that explains the possibilities of being a United States senator.” What Biden came to view as integrity and statesmanship involved placing decorum, norms, and consensus above the life-and-death consequences of the Senate’s action—even if it meant splitting the difference with the likes of John C. Calhoun.

The celestial callings of truth-telling, bipartisanship, and “integrity” have always provided a high-minded veneer to what looks suspiciously like a willingness to do whatever political opportunity requires. Biden has long fashioned himself as a rhetorical opponent of money in politics; he dedicated his first speech on the Senate floor to the issue and was still harping on it in his 1988 presidential campaign. At the same time, as Marcetic notes, even Biden’s early campaigns were lavishly funded, increasingly by big donors across the political spectrum. His first presidential campaign drew on the expertise of MBAs and hires from Wall Street who designed a gamified donation system that sold donors different tiers of access to Biden. As George Packer reports in his 2013 book, The Unwinding, Jeff Connaughton, one of those Wall Street hires, would tell Biden bundlers, “For fifty-thousand dollars I can get you dinner with the senator at his house. For twenty-five thousand I can get you dinner with the senator, but not at his house.” Biden’s aggressive defense of the Delaware financial and credit card industries and intense opposition to bankruptcy reform in the late 1990s came at the same time that one of the largest Delaware credit card firms, MBNA, was a major donor. Biden sold his house to a donor who was an MBNA executive, and the firm, after hiring his son Hunter out of law school, paid him a monthly consulting fee when he became a lobbyist. These entanglements earned Biden the nickname “the senator from MBNA.” In the course of his current campaign, he’s presented the health care, financial, and fossil fuel industries with their best defense against popular reforms, remaining attractive to corporate donors.

The great negative space of Biden’s political career and his rhetorical justifications for it—the missing element that renders the whole coherent—is the absence of any sense that politics, even just sometimes, might involve fundamental conflict or zero-sum interests. In this respect, Biden could be a stand-in for virtually any late-twentieth-century Democratic politician or for the party as a whole, though he was an early adopter of and an energetic advocate for all-things-to-all-people shape-shifting. Rather than, as he puts it, taking principled stands and making nobody happy, Biden and the Democrats have jettisoned principles for “pragmatism” and tried to make everybody happy, including the implacable enemies of the well-being of their core constituencies. Biden has always acted as if were possible to stand for both capital and labor, both racist suburbanites and their African American targets, both the defense of good government and radical anti-government insurgency, both a massive carceral state and civil liberties, both corporate millions and a fair democracy. The virtue, the courage, the integrity, was in finding the sweet spot in between, regardless of the fact that the huge imbalances between these interests meant effectively siding with the wealthy and powerful.

It is this fundamental conviction that raises the toughest doubts about Biden’s ability to confront the crises of 2020. Biden’s long involvement in the hard-right turn of American politics can always be waved away in the present as a set of forgivable compromises from the past, but the lessons from it that he still champions today cannot. His history of lionizing bipartisanship with segregationists might be less concerning had it not become the unshakable core of his political identity. In many ways, the most alarming section of Yesterday’s Man takes place during Biden’s vice presidency, when Marcetic argues that Mitch McConnell viewed Biden as the “soft underbelly” of the Obama administration. McConnell was, of course, pioneering a sweeping form of institutional obstruction that would stymie Obama’s mild agenda and later thunderously deliver on Trump’s radical one. As McConnell repeatedly held the government hostage over the debt ceiling, Biden outraged Democrats by offering concessions that had not been on the table. On the 2020 trail, Biden has held forth on his worries about the Democrats having “too much power” and mused about a Republican running mate. There is, as yet, no indication that Biden has the slightest comprehension of the nature of Republican power despite observing its rise firsthand over four decades.

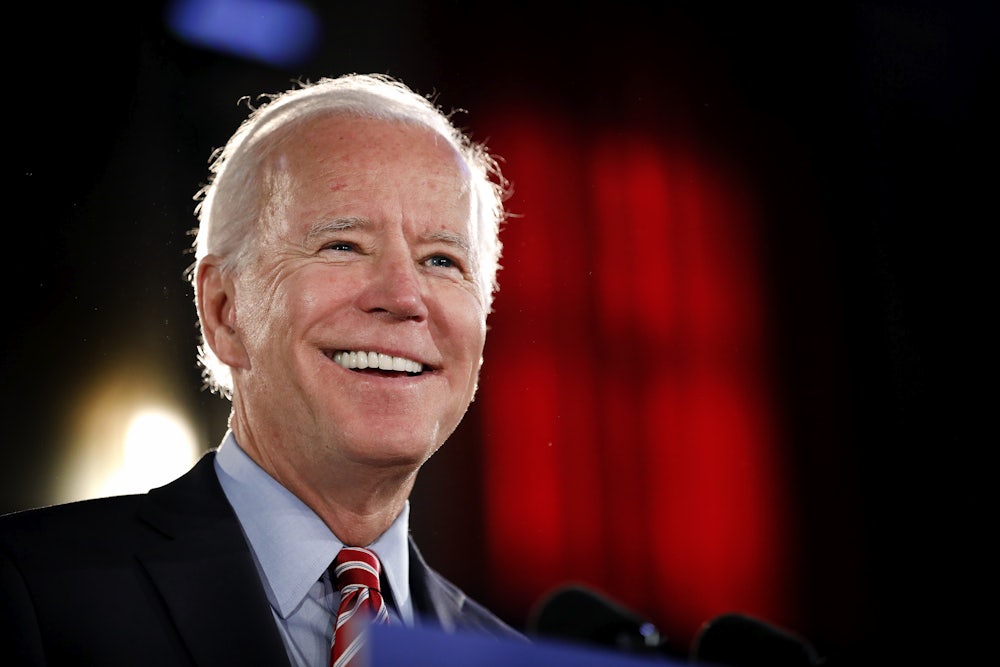

The magic of the Joe Biden of 1988 faded long ago, giving way, as Peter Beinart wrote in The New Republic during the 2008 Democratic primary, to a “windbag” who was “in danger of becoming a laughingstock.” Biden’s tenure as vice president raised his status to charming but slightly embarrassing elder statesman, subject of Onion headlines and Gawker posts, chosen in part because no further presidential ambitions seemed possible. Obamaworld saw him with affection, but as one Obama insider put it, “Joe Biden’s story is 30 years past due.” Until Biden’s stunning turnaround in the South Carolina primary at the end of February, the absence of his once-celebrated persona was palpable in what a New York cover story labeled his “zombie campaign.” His well-publicized gaffes—saying parents should “make sure you have the record player on at night,” calling a young New Hampshire voter a “lying, dog-faced pony soldier”—might be seen as efforts to bottle the old lightning, the disorientation of his “gut” style of “getting the connect.”

But the conditions of the 2020 primary proved extraordinary, with a field of largely unsatisfactory pretenders crowding in for the chance to do battle with a historically unpopular president. Fear has become the central issue of the campaign, with high numbers admitting they are willing to vote against the positions they prefer on the issues they care about most for what they have been told is the best opportunity to defeat Trump. After decades of alarming Republican politics, Democratic voters have been trained to set aside their hopes and interest for higher strategic purposes (much as in 1988, with Biden’s help, they were turned away from Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition). The fear election has, remarkably, opened the possibility for the empty vehicle of Joe Biden one last time.

Biden’s 1972 Senate campaign drew remarks at the time for attracting small donations and battalions of enthusiastic young volunteers. “The comments of the young [Biden] volunteers are often one squeak above the equal of a Beatlemaniac,” a Delaware journalist observed. Local Democratic leader Henry Topel said he was “never so surprised to see young people manning the phones—an army of youth.” Biden was propelled by the fact that it was the first election in which 18-year-olds could vote. He even trumpeted his grassroots support and savaged the corporate donors behind his opponent. Later, the slickest Democratic Party strategists of 1984 and 1988 still saw him as a vessel for future-oriented optimism, for a message of generational change.

Biden 2020 stands for a different kind of optimism, a darkened and diminished hope for the fleeting recovery of the past. He is as vague and adrift as ever. Only this time, the justification for his candidacy has finally manifested itself. He cultivated it, certainly, in his long decades as a fighter for reduced expectations. But its sudden affixture to his previously ailing campaign and his diminished person has taken place through no effort or inspiration of his own. He largely lacks support from the youthful forces that first vaulted him to power; today’s younger voters have come of age amid decades of capitulation and compromise. They will have to hope for the best as many Democrats are borne forward on the current of how, during a pivotal moment this spring, Joey made them feel.