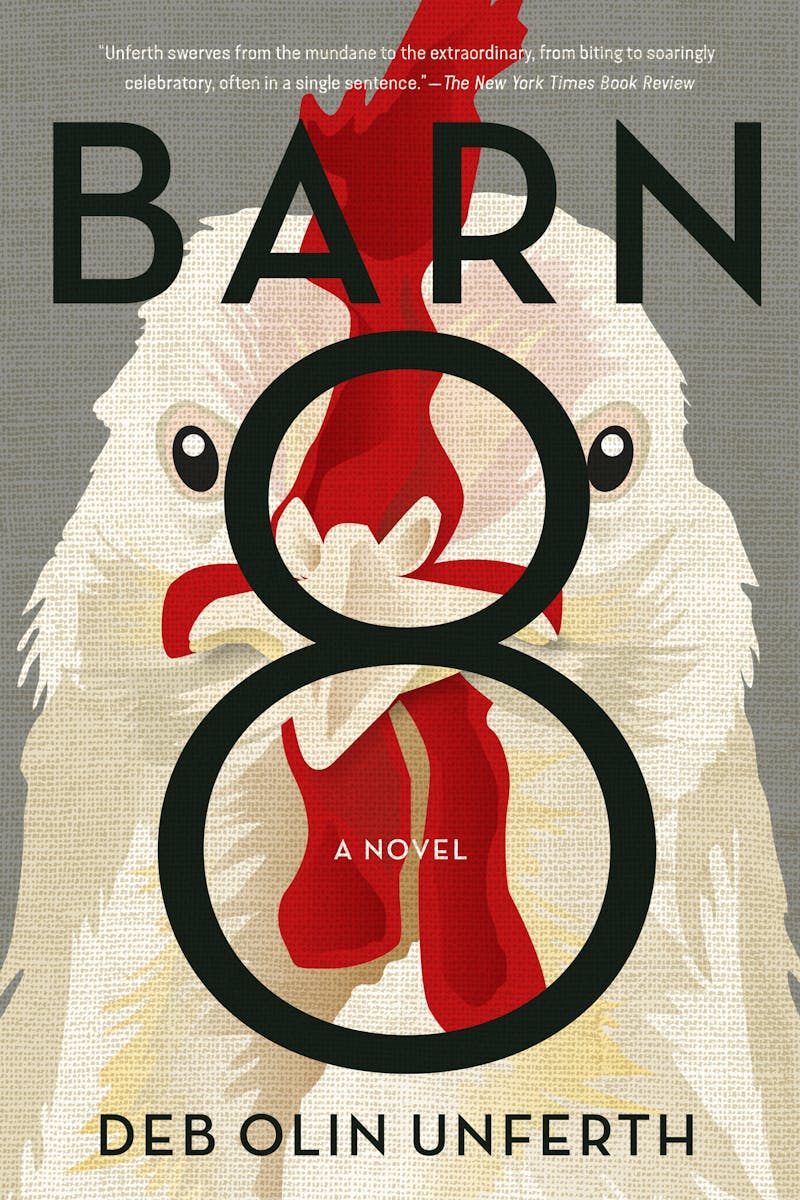

I’ve flirted with vegetarianism the way you might with faith on a turbulent flight. I’ve made New Year’s resolutions; I’ve joined the mail-order bean club. Declining to eat meat may seem like a refusal, but it is in fact a belief. And while it’s not the intention of Deb Olin Unferth to proselytize, her new novel, Barn 8, still feels like the start of one road to Damascus.

Barn 8 begins with Janey, a lost soul who makes an impulsive teenage choice and upends her entire life. “No, it was not her only mistake, but it was certainly her greatest, as others have great loves, great ideas, or great tragedies that befall them,” Unferth writes. I’m avoiding the spoiler, just know that Janey ends up in Iowa, then ends up an auditor for the egg industry, then ends up an activist radicalized by the things she witnesses: birds mangled by machines, the endless amounts of excrement, the inhumanity of it all.

The novel feels researched but not pedantic. I learned that hens are disposed to lay about 30 eggs a year, but farmed hens provide 270. As Cleveland, Janey’s principal collaborator, explains to her/us: “American scientists in the 1930s figured out that light is how the hen’s body knows when to lay. Long light means spring and laying. Less light means winter and rest. More light, more laying.”

Unferth doesn’t intend to gross us out, but her book doesn’t look away from commercial agriculture’s attempts to adapt nature for the market. You can see why Janey and Cleveland would wrangle a group of activists, all seasoned infiltrators of the industry, to attempt the preposterous act of liberating thousands upon thousands of chickens from one particular farm.

Their experiences in the barns had strengthened their convictions. They’d spent twelve-hour days placing the baby-soft beaks of chicks into hot-iron guillotines, searing off the tips, while the chicks struggled and their faces smoked. Hens. Sweet little puffs. The solid adventure of saving them: Who didn’t want to be part of it? Who wouldn’t? The time had come to say no more.

We spend a fair amount of time with Janey. She’s well-drawn, if the author relies a bit too heavily on a device in which the character imagines an alternate self, living according to the paths not taken. But it’s when the heist plot kicks in, and we meet a whole parade of well-intentioned kooks, that Barn 8 comes alive. Counterintuitive, maybe, but the caper reveals how serious a book this is.

That is not to suggest the novel is a catalog of horrors or a sanctimonious lecture. There’s a joy here, in no small part because of Unferth’s sentences, which are muscular and musical and confident. Beyond Barn 8’s political concerns is an interest in life itself—the miracle of existence, whether human or otherwise. I admit, however, that I rolled my eyes when the author entered the consciousness of one of the hens:

Hen, alone, strolling away from the eight looming apparatuses of Happy Green Family Farm. Her first steps on dirt, not wire. Where was her mother? Only a little over a year old, orphan from egg crack. Who knew where she thought she was going (why did the chicken cross the road?) or whether chickens “think” about such things as destination (of course they do—not quite the way we do, but close enough). You had to root for her.

I admit, too, that this is some of the novel’s gutsiest stuff. I’m sidestepping another spoiler, but even if you think this is silly, stick with it. The author is having fun but not joking around (crucial distinction), and the novel’s conclusion builds on the passage above in a way that’s quite remarkable.

For those who believe in animal liberation, the question is not political, but moral; my own wavering about the consumption of meat may be unimaginable to them. I was expecting (fine, dreading) a novel that simply gave voice to that conviction, that yelled at a wall. But Unferth is writing in good faith, and she’s also talking about something bigger. She’s a capable guide to the unsettling feeling that governs modern life, a feeling that is very much tied to the billions of animals we eat every year.

Think high-rises, gated communities, all the places that give you a twitch of existential dread. The Amazon shipping facilities, the dying superstores, the prisons and detention centers, the pig farms, all the boxes that hold products and people and animals, the LeCorbusian landscape one skirts over or through, avoids. Think of the smaller boxes that we press our faces to, think of all the tiny digital boxes we touch with our fingers to signal alliance, passion, smarts, nostalgia, enmity, the whole of our minds.

This passage makes Barn 8 sound heavy-handed, but know that it is also very funny. The activists are both well-meaning and annoying, the plot they hatch to rescue the chickens both impressively thought-out and entirely absurd. It’s a bit of a relief to laugh. Annabelle, one of the activists, explains:

Humans won’t volunteer to do anything but destroy. They will have to be forced out. And no one can make them do it—not any other animal, not even nature. But no one will have to. They’ll do it themselves. And that moment when they go? It will be an opportunity.

While I don’t want to reveal Barn 8’s ending, this passage gives you a sense of it. Humans have just about finished the hard work of destroying ourselves, and we’re seeing more and more art that mourns that fact. This novel does that, with a sly grin. We might be sad about the end of humanity, but the chickens are probably relieved.