Thanksgiving 1972 was a bad one for Mimi Galvin. When she and her husband Don went out to dinner with his Air Force colleagues and their wives, she liked to project the image of a proud mother of an all-American brood. But Mimi was on the brink of losing control. The two eldest of her 12 children were fighting, and she could only watch as their brawl spilled into the dining room and upended her perfect holiday table. She walked into the kitchen and smashed her special Thanksgiving gingerbread house into bits.

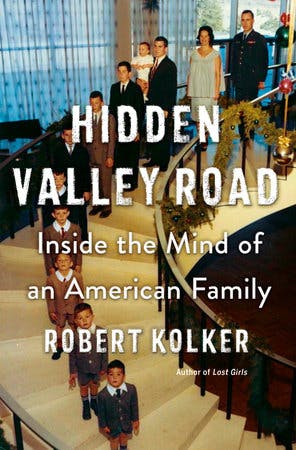

Mimi’s heart, her image, and the gingerbread house are among the many broken things in Robert Kolker’s new book Hidden Valley Road. Named for the street the Galvins lived on in Colorado Springs, Kolker’s book splices the history of their family with an account of the gradual rise of genetic research in studying and treating mental illness. The Galvins present an extraordinary case: Six of Mimi and Don’s ten boys developed schizophrenia, striking at the heart of a debate over whether nature or nurture determines who we are.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) states that a schizophrenic person must experience at least two of the five qualifying symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms like apathy or anhedonia. That loose definition is the result of a century of argument, experiment, and loss.

In 1903, a German judge named Daniel Paul Schreber published Memoirs of a Nervous Illness, an account of his psychotic break and subsequent treatment in an asylum. He believed he was communicating with people along “divine rays.” The Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler coined the term “schizophrenia” at around the same time. (Schizo is Latin for “splitting,” but Bleuler meant it to refer to the split between the inner and outer lives of the patient, not split personalities—a woefully long-standing misinterpretation that Kolker corrects.)

Freud believed it was Schreber’s upbringing that caused his disorder; his protege Carl Jung held there must be some hereditary component to the breakdown. In the mid-twentieth century, when Mimi was raising her many children, nurture was the order of the day. Psychiatrists like Frieda Fromm-Reichman were keen to attribute an array of neurological and mental illnesses to bad parenting, particularly the “domineering mother” who, in Fromm-Reichman’s words, caused the “severe early warp and rejection” of the schizophrenic mind.

When the Galvin family began to fall apart, they fell straight into the arms of a medical profession ready to blame their mother. When the eldest son Donald began to believe he was the child of an octopus, Mimi took him to the doctor. What she heard was that it was all her fault. Her solution was to look after her boys herself, with heavily-medicated spells in the local mental hospital sprinkled in when one of them got violent.

In every way, the Galvin boys’ courses of treatment reflect the conventional thinking of the last century, often much to their detriment. Schizophrenia drugs have only been through three major rounds of development, with first-generation antipsychotic drugs invented in the 1940s, and second-generation “atypical” antipsychotics in the 1960s and ’70s. These can be extremely effective in treating schizophrenia’s symptoms, but are now well-known to cause tardive dyskinesia (the jerky tics and stiffness one associates with a bad stereotype of an “insane person”) and a range of other deleterious effects. There’s only one third-gen drug, Abilify, and that’s not free of side effects either.

Schizophrenia ransacked six of the Galvin boys’ minds: Their hallucinations turned to full delusion, and some of the boys’ anger transformed into violent rage and paranoia. Meanwhile, the treatments they received damaged their health severely. Two died of heart problems. As young men they were all handsome; in their middle age, the surviving schizophrenic brothers had limited physical mobility because the drugs had made them obese. Mimi was emotionally scarred by the blame laid at her feet by the psychiatric profession. Worst of all, her unwell children distracted her so badly that she missed the fact that more than one of her sons was sexually abusing her two daughters. (To be clear, and Kolker is not clear enough in the book, sexual predation is not an inevitable feature of schizophrenia.)

A few scientists—who still lack a solid etiology for schizophrenia—have made progress in trying to identify the genetic markers of the illness. But in 2000, drug titan Pfizer informed a research scientist named Dr. Lynn DeLisi that they were pulling her funding. By this point, she had been researching the potential genetic origin of schizophrenia for over three decades. She had assembled an enormous set of samples from families with more than one schizophrenic member, including the Galvins’, operating on the theory that drugs could be developed to target genes that created similar pathologies in siblings.

So, why was her funding pulled? Because existing medication, though flawed, effectively pacifies patients so well that there was no financial incentive for Pfizer to replace it quickly.

Other scientists would recover DeLisi’s samples about ten years later, realizing the potential that had been quashed. But Pfizer’s penny-pinching slowed down the research in an outrageous fashion, a scandal underlined here by the sheer volume of the Galvin family’s suffering. Over and over again the boys fight, break down, enter the local mental hospital, come home, go off their meds—then start the cycle all over again. Their bodies deteriorate. People die.

Meanwhile, the old debate has no resolution. After the human genome was fully sequenced in 2003, researchers in the genetics of mental illness found no “smoking gun” that causes schizophrenia in some people and not in others. Schizophrenia is probably caused by some combination of nature and nurture, with many genes and environmental factors (such as childhood abuse) collaborating to produce the condition. As genetic science develops, it delivers ever more complicated data. As Kolker puts it, “Where the conversation once was about Freud, now it’s about epigenetics—latent genes, activated by environmental triggers.”

The surprising lesson of Hidden Valley Road is that schizophrenia has long been a literary subject. It entered public consciousness through memoir and is still, in Kolker’s work, best examined at length, in writing. In narrating the history of a family whose many unwell members would have a hard time articulating their own experiences, Kolker works towards a common language of the mind.