“I live on a relatively grand scale, because that’s the way fashion is,” André Leon Talley wrote in his 2003 memoir, A.L.T. “By its very nature, it is larger than life. It’s fickle, it’s flamboyant, and it’s fabulous.”

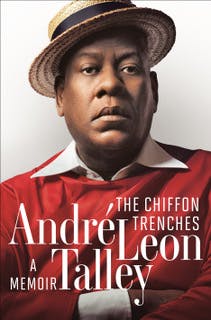

Though sprinkled with gossipy tidbits (Betty Catroux wore boys’ T-shirts beneath her YSL couture! Halston served dinner guests baked potatoes and piles of cocaine!), A.L.T. is less a book about fashion than a story of a sensibility and how it was forged. It’s a story of a black man from the South improbably rising to the very top of the systems of fashion and publishing—the intersection of money, influence, glamour, and power. It’s the story of queerness sublimated into taste: a reverence for indomitable women, luxurious objects, sensual (but never sexual) pleasures. It’s the story of the flamboyant and the fabulous. Now, 17 years on, Talley has finally got to the fickle, in his new memoir, The Chiffon Trenches.

Yes, it’s more of the same—incredibly, Talley repeats the anecdotes about Catroux and her T-shirts and Halston and his cocaine. But the vantage is different, Talley more exile than insider. This is an account of his excommunication from the inner circle by his friend of many years, the designer Karl Lagerfeld, before Lagerfeld died in 2019. It’s a public reckoning with Vogue, his longtime perch, where he is now an emeritus presence. It’s the cautionary tale of a man whose influence has diminished in inverse proportion to his girth, for fat is a cardinal sin in the beau monde, which manages to be both hedonistic and ascetic.

If you know him only as the camp loudmouth on Entertainment Tonight gushing over starlets walking the red carpet there’s some useful context here. Talley was raised by a great-grandmother and grandmother who boiled the laundry and ironed the sheets. This fact may illuminate his kinship with Mrs. Vreeland (never Diana!), the legendary editor of Vogue who took Talley up as a protégé, with her closet full of Porthault linens. Talley did his master’s at Brown—his thesis: “North African Figures in Nineteenth-Century French Painting and Prose”—and a classmate’s father brokered an introduction to Vreeland, who had gone to the Metropolitan Museum of Art after S.I. Newhouse dismissed her from Vogue. Talley worked alongside her in the Costume Institute, an unpaid “volunteer,” then Vreeland sent him off to Andy Warhol, who hired Talley at Interview.

That magazine assigned Talley to profile Lagerfeld. “We spoke about the eighteenth century: the style, the culture, the carpets, the people, the women, the dresses, the way the French entertained, set a table,” he writes. You assume there’s exaggeration in Talley’s bluster, but it’s not difficult to imagine these two bonding over French carpets. The meeting ends with the designer beckoning the journalist into his bedroom, not for an assignation but to give him some bespoke hand-me-downs from Hilditch & Key: “silk crêpe de chine shirts in kelly green and pink peony, each with a matching scarf.”

Talley graduated to a gig at Women’s Wear Daily, working for the legendary John Fairchild. (“A kind of god,” Talley writes. “He could destroy a designer by refusing to cover them.”) Fairchild pushes Talley to see:

From him I learned how to embrace what was going on around me in 360 degrees. What makes a beautiful dress? Hems, seams, the way it’s put together. The ruffles. How’s the ruffle? How’s the bow tie? What’s the combination of colors, what’s the combination of fabrics? There’s Mounia on the runway, in what? What was Yves’s inspiration? What is the music behind her? And what is the chandelier behind her? And there are roses, why are they there? Why is she wearing that shoe? And what is the lipstick? What is going on in the mind of the designer?

Knowledgeable and outré, Talley thrived, charming the industry’s aristocrats like Oscar de la Renta and its arrivistes like Halston (queers from the provinces have always done well in New York; look at Warhol):

I glided through this world with extreme caution and my usual armor: my fashion choices. Banana cable knee socks and elegant moccasins. Or Brooks Brothers penny loafers. Neckties, my Karl Lagerfeld castoffs, and Turnbull & Asser shirts. I never spent a dime on drugs. My money was spent on luxury.

He was promoted and dispatched to Paris, where Lagerfeld took especial interest in him. “People thought I was Karl Lagerfeld’s lover,” Talley says. “I was not. Nor was I ever. Nor was I Diana Vreeland’s, as some people gossiped. There is always the thought that as I am a black man, it can only be my genitals that people respond to.” No wonder he needed that fashionable armor: “I depended on sartorial boldness to camouflage my interior vortex of pain, insecurity, and doubt.… I never wanted to look like anyone else.”

Paris was splendid but cruel. A WWD exec accused Talley of sleeping with every designer on the scene. “I was just a big black buck, sent to satisfy the sexual needs of designers, be they man or woman—I had no talent, no point of view or knowledge of fashion.” A friend told Talley that another fashion habitué had been referring to him as “Queen Kong.” “It’s the worst kind of pain,” Talley writes. Lagerfeld bought Talley a ticket back to New York.

These anecdotes made me wince, remembering Hilton Als’s 1994 New Yorker profile of Talley, a text I pored over as a closeted teen (like teenage Talley reading Vogue at the library!). The piece ends at a luncheon Talley organized during the Paris couture, the guests all lining up for a group photograph. Loulou de la Falaise—long a designer and muse at Yves Saint Laurent—complains, “I will stand there only if André tries not to look like such a nigger dandy.”

Back stateside, Talley interviewed with Grace Mirabella (Vreeland’s successor at Vogue, herself succeeded by Anna Wintour in 1988). Talley claims Mirabella said: “I remember you … sitting in the front row at Claude Montana, madly applauding the collection on the runway. And then I saw you at Thierry Mugler, clapping loudly. Why is that?” How could patrician Grace Mirabella, champion of Donna Karan’s commonsense chic, understand the provocations of Montana and Mugler? Her question contained a disdain for Talley’s exuberance, or really his queerness and blackness.

Indeed, fashion is perhaps his only expression of the former. “Sex confused and bewildered me,” Talley writes. “In respectable Southern black households, it was simply not discussed. Physical intimacy of any kind was kept to a bare minimum.” He writes of his sexual abuse at the hands of a neighbor, then a succession of local boys. It’s terrible, and the ramifications are clear to the reader even if they’re largely unexamined (on the page anyway) by the author. “Love has not been in my life in any degree,” he tells us. “I have had many emotional highs and definite lows when it comes to love and romance, and yet I am alone.”

The Chiffon Trenches has been much talked about for the promise of dish. There is that. It’s hardly illuminating (Karl Lagerfeld was a nut; Anna Wintour is dogged), though the specifics are delicious. Divulging what Talley has to tell will spoil one of the pleasures of the memoir, but the book is less interesting as gossip than it is as a correction of the record, the man insisting on defining his legacy.

He wants to have his say, even if that’s rude. “Vogue was a culture of deportment, a culture of manners. This was all unspoken, yet it was crystal clear. Flowers were sent and thank-you notes were handwritten,” Talley writes. It’s a violation of that culture of deportment for him to tell all, but important to declare his life an accomplishment of blackness. He is right to. This is a man whose friend called him a “nigger dandy.” What must his detractors have said?

Talley knows that the world has changed (imagine Grace Coddington flying coach!) but cannot quite comprehend the betrayal. He assumed Wintour would choose loyalty to him over page views. He believed Lagerfeld’s largesse and Wintour’s loyalty made him rich and powerful as well. Talley is maddening, but he breaks your heart. The writer’s voice is like his body and personality: unruly. I kept fretting: André, girl, what are you thinking? Don’t imagine this book a burned bridge: You know that if Wintour beckoned, Talley would run to her.

Talley, now 70, writes wistfully of how, after her dismissal from Condé Nast, Diana Vreeland’s pals looked after her. I do hope one of the spoiled millionaires he spent his career trumpeting will return the favor and see to Talley’s care. As Hilton Als noted, Talley was the only one for so long—in Talley’s words, “the only black man among a sea of white titans of style.” British Vogue is now run by a black man, Edward Enninful. Another black man, Virgil Abloh, designs the men’s collections for Louis Vuitton, while LVMH has gone into business with Rihanna. Talley isn’t the only one anymore, the fruit of his years in the trenches.