On Friday, House Democrats are all but certain to pass a bill making the District of Columbia the nation’s fifty-first state, marking the first time in history a house of Congress has formally approved statehood for the District. Naturally, the bill is doomed in the Senate, for reasons President Donald Trump candidly explained in May. “D.C. will never be a state,” he told The New York Post in an interview. “You mean District of Columbia, a state? Why? So we can have two more Democratic—Democrat senators and five more congressmen? No thank you. That’ll never happen.” Purely to drive the point home, the White House announced Wednesday that Trump would veto the bill even if it were passed by the Senate.

In rejecting statehood, the Republican Party is denying those seats not only to Democrats, as a partisan matter, but to the 700,000 District residents who have no real voting representation in the Congress that governs them. As is commonly pointed out, the city is more populous than two states, which, like every other state, each have two senators and full members of the House. The situation is even less defensible than most Americans vaguely informed about the District’s status likely realize: The problem is not only that residents lack a meaningful say in national affairs but that the city’s municipal policies have been attacked and undermined by conservative members of Congress from elsewhere in the country, who take full advantage of Congress’s constitutional authority over the District’s laws and budget. Washington’s position was recently brought into particularly stark relief with President Trump’s deployment of military and federal law enforcement personnel against the District’s peaceful demonstrators earlier this month.

The District’s status is a product of both the Constitution’s provision establishing the city as a federal district (which drew complaints from residents even then) and simple racism. As the city’s Black population boomed, in the 1950s and 1960s, the debates over its autonomy and representation came to reflect the nation’s racial divide. In a representative moment in 1972, Louisiana Congressman John Rarick, a conservative Democrat, argued before the House’s committee on the District that the city lacked a “proper racial balance” and would be taken over by black Muslims if granted the authority to govern itself. When another congressman interrupted Rarick to remark that he was “a leading racist in the Congress,” Rarick’s reply was simple: “That’s why I’m opposed to home rule.” Yet the rationale for rectifying the city’s situation was clear and strong enough by the end of the 1970s that Congress passed, on a bipartisan basis, a constitutional amendment granting the District two senators and a voting congressman in the House—a measure vociferously supported even by ex-segregationist Strom Thurmond. But the amendment was never ratified by the requisite number of states, and waning congressional interest in the District’s status after its failure helped shift activists toward full statehood for D.C. as an alternative strategy.

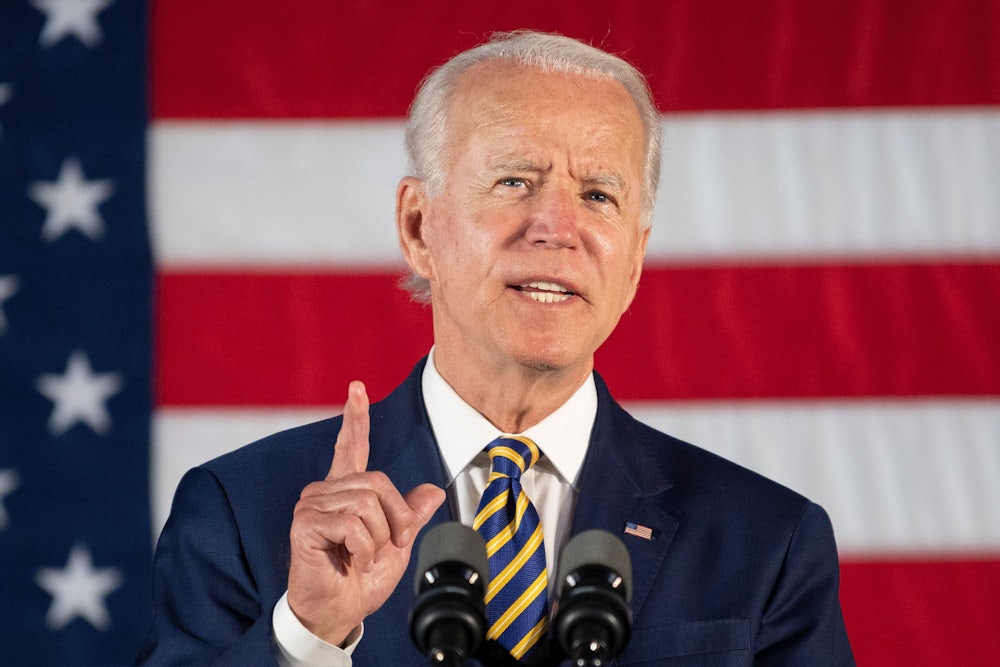

In sum, the push for statehood is not only justifiable on its own merits but also animated by concerns so unassailably valid that Congress approved the amendment of the Constitution to address them decades ago. But Trump is not wrong to say that statehood would increase Democratic power in the Senate. This is, in fact, among the primary reasons why the Biden administration should make statehood a priority if he wins in November. It has been estimated that by 2040, 30 percent of the American population—concentrated in whiter, older, more rural, and thus more conservative states—will control 68 percent of the seats in the Senate given the upper house’s apportionment scheme and current population trends. It doesn’t take much math or demographic projection to understand that Republicans already have enough disproportionate power in the Senate to defeat legislation on climate change, health care, gun control, and other issues that a majority of Americans would support.

The fate of the Biden legislative agenda, the general future of federal Democratic policymaking, and the legitimacy of Congress as a democratic institution all rest upon whether Senate Democrats will decide to even the balance of power in the chamber—not just for their own party, but for Americans now penalized in one of the chambers necessary for passing major legislation simply for living within the most populous parts of the country. Statehood for the District and the addition of two reliably liberal senators from a large city would help, as would the elimination of the legislative filibuster, which effectively imposes a supermajority requirement for the passage of most bills. In fact, statehood will not pass the Senate unless a Democratic Senate majority kills the filibuster. However well Democrats do on Election Day, they will not be returning to the Hill in January with 60 Senate seats.

Yet, while support among Democrats for statehood has generally been high in recent years—both Barack Obama and Bill Clinton endorsed it during their presidencies—Democratic senators and other party leaders have been apprehensive about touching the legislative filibuster. There are signs things could change rapidly if Democrats win the Senate and Biden wins the White House: Numerous Democratic candidates expressed their support for, or at least their interest in, ditching the filibuster during the primaries. Chris Coons, among the senators most famously committed to the institution’s norms and a close ally of Joe Biden, said in a profile that ran this week that he wouldn’t let Biden’s agenda be stymied by Republican obstructionism. “I am gonna try really hard to find a path forward that doesn’t require removing what’s left of the structural guardrails,” he told Politico, “but if there’s a Biden administration, it will be inheriting a mess, at home and abroad. It requires urgent and effective action.”

The big question is whether Biden himself feels the same way. What the Senate does isn’t technically up to him, but he would obviously have significant sway over Democrats in Congress as president and as the Democratic Party’s standard-bearer. As it stands, Biden supports statehood and has for years now. But he’s repeatedly expressed opposition to eliminating the filibuster for any reason and insisted that Republicans will be willing to help pass Democratic policy priorities once Trump loses.

“There are a number of areas where you can reach consensus that relate to things like cancer and health care and a whole range of things,” he told The New York Times in January. “I think we can reach consensus on that and get it passed without changing the filibuster rule.”

This is a fantastical assumption. Incidentally, the statehood advocacy group 51 for 51 has claimed that Biden supports eliminating the filibuster to pass statehood, presumably on the basis of a recorded exchange Biden had with one of its activists at a February campaign event. But the video of this 10-second conversation, in which the activist quickly asks Biden whether he supports passing statehood “with 51 votes in the Senate,” leaves it unclear as to whether Biden was aware he was being asked specifically about the filibuster. (The Biden campaign did not respond to repeated requests for comment on this article.)

The statehood effort found a new villain, this week, in Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, who delivered a speech rehashing many of the tropes statehood opponents have trotted out over the years. At one point, he argued Wyoming is more deserving of representation than D.C. because it has more people employed in manufacturing and construction; at another, he asked whether the American people should entrust the likes of the late Marion Barry with the powers of a governor—echoing the rhetoric of Rarick and other racist opponents of rights for the District. These remarks drew indignation and condemnation from Democrats on social media, as they should. But the fact of the matter is that Tom Cotton will have functionally no say in whether the District of Columbia is admitted as a state if the Democrats hold the House and take the Senate and the presidency in November. It’s entirely up to Biden and his party whether they will take the step necessary to pass a statehood bill in the Senate. At the moment, there is ample reason to believe they might not.