Wellness influencers are the Romantics of our age. The toned women in leggings Instagramming their flowers and muscles and bowls of miraculous grains are mimicking Shelley or Wordsworth’s rapture. Like those poets, the wellness influencer sees with “an eye made quiet by the power / Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,” high on pretty pictures and their own sincerity.

In his 1958 collection of lectures, English Satire, the scholar James Sutherland argued that satire is the literary enemy of the Romantic. Where a man like Wordsworth “was at the height of his receptivity when he loved and was happy, when his feelings were vibrating in unison with all living things,” the satirist stands “apart from the object of his contemplation, critical, hostile, contemptuous, at war with his world,” and therefore unable to “attain to any wholeness of vision.”

Sutherland was building up to an explanation of Bernard Shaw’s satirical plays, which asked middle-class audiences to question the conditions of their reality, but his point stands. It follows that satire ought to be the best rejoinder to the wellness influencers, who conceal their contradictions and flaws behind an artificial lacquer of faux-vulnerability. “I have a confession,” some beach snap caption begins, before ending in a sponsorship disclosure.

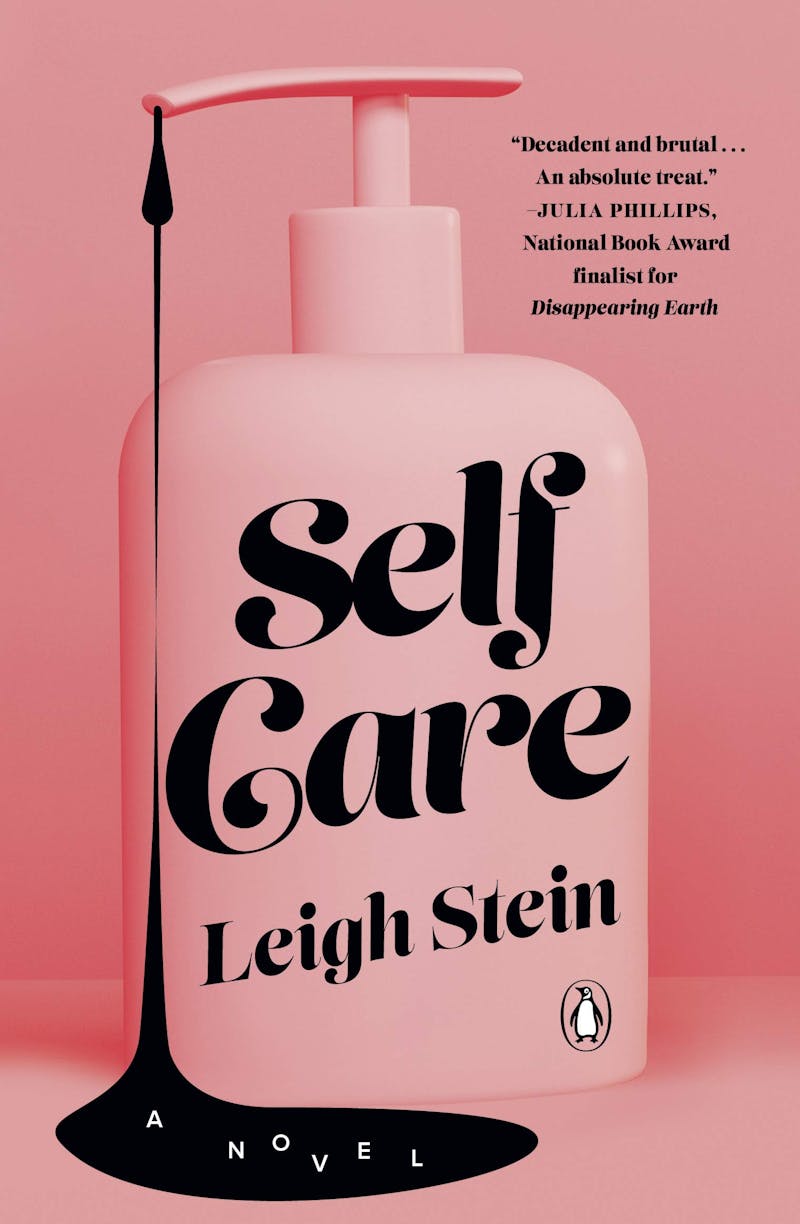

The medium is Instagram, but the commodity bought and sold is self-care in its corporatized form. Enter Leigh Stein, author of the new satirical novel Self Care, about the catastrophic fall of two female co-founders of a “wellness community” called “Richual.” Stein has her own experience with wrangling women online, since she ran a semi-secret Facebook group of 40,000 women users from 2014 to 2017. What began as a riff on Mitt Romney’s gaffe about having “binders full of women” evolved into a nonprofit called Out of the Binders/BinderCon, of which Stein was the co-founder and executive director. (I was an early member but left after threads of outraged infighting turned the original Facebook group into a Charybdis of mutual loathing.) She’s also the author of a lost-millennial novel, The Fallback Plan; a poetry book, Dispatch From the Future (both 2012); and a nonfiction book about an abusive relationship, Land of Enchantment (2016).

In Self Care, Richual is the brainchild of two women, Devin and Maren, and the narrative reins switch between them and one of their senior employees, Khadijah. Devin is an heiress and face of the brand who spends her working days doing yoga, scraping her tongue, and “tapping the energy meridian points on [her] face using the Emotional Freedom Technique: ‘Even though I have to appear perfect to survive,’ she repeats to herself, ‘I deeply and completely accept myself.’”

This is of course bullshit, as Maren knows. The brains behind the operation, Maren pities Devin but is in thrall to her own problems, drinking wine by the case and easing her raging insecurity by working all day. Richual is not just a startup, it’s a community, the branding says. But actually, it is a startup, and while Devin is at Soulcycle, Maren is crunching the numbers.

If Maren is the swan’s frantically paddling feet, Devin is the graceful part of the bird you can see. Like The Wing or that Moon Juice lady we all love to hate, the Richual business is aimed straight at women’s hearts. “Richual asked,” Maren recalls, “when’s the last time you put yourself first?” The Richual aficionados use it as a “digital sanctuary” that runs on pain and competition. Devin posts pictures of her hot skinny body (she has an eating disorder) to inspire the masses to cleanse their guts. App functions let you “track your meditation minutes and ounces of water consumed and REM sleep and macros and upcoming Mercury retrogrades and see who among your friends was best at prioritizing #metime, based on how many hours a day they spent on the app.”

The company’s revenue comes from brands that offer relief, via “serums and creams, juices and dusts, clays and scrubs, drugs and masks, oils and enemas, scraping and purging, vaping and waxing, lifting and lengthening, straightening and defining, detox and retox, the cycle of life.” In a Q&A distributed by her publisher, Stein describes the moment in 2017 that this particular paradox came to the cultural fore. After Trump’s election, there was both “outrage and disbelief on the left … and a call to practice self-care when you needed a break from the 24/7 outrage that was your civic duty.” Companies “capitalized on self-care as a marketing strategy” with shocking speed. This isn’t a new observation, though it feels new for fiction.

Stein’s light touch keeps her tone sparkly, but when the subject of sexual assault comes up, things darken. Although Self Care is a mite too short to do justice to its subject matter, Stein throws a classic accusation of abuse at one of Richual’s most important investors. Devin doesn’t believe it, since she herself has been sleeping with the investor. As Doreen St. Felix wrote this week in a review of I May Destroy You, some of the most interesting narratives around rape written by young women today investigate the perils and luxuries of victimhood and the ways social media invites us to spin our stories of triumph over adversity into #content.

Richual is another example of the personal being made commercial. As with so many supposedly feminist capitalist ventures, the vulnerabilities of its own charismatic founders render it brittle. Stein said that she was inspired by “what happened in 2017, when the actress Aurora Perrineau made sexual assault allegations against Murray Miller, a writer on the TV show Girls, and Lena Dunham and her partner Jenni Konner initially defended Miller.” (They later apologized.) Over and over again, Richual’s real-life analogs (or their financial backers) have staked their reputations on the public image of their founders (Audrey Gelman and The Wing, Dunham and Girls, Amanda Chantal Bacon and Moon Juice) in a way that all but guarantees failure, since an individual will never be able to satisfy every consumer with their life choices.

Since so many of those companies have faced accusations of racism, Self Care almost by necessity deals with race in Khadijah’s sections. Maren has always been concerned about compensating Khadijah, the company’s first hire, fairly, and once tried to give her 5 percent of Richual “as reparations.” (Devin talked her down to 2.5 percent.) Despite all their public “badassery” around protecting women, neither Maren nor Devin can find a minute to listen to Khadijah’s actual problems, which build over the course of the novel until we cannot but wish she would walk out the door with a match thrown over her shoulder, like Bernadine in Waiting to Exhale.

Race and class are the issues that prove Devin and Maren are not fit company executives. “I agreed that I was white,” Devin thinks in one of her chapters, “but I didn’t feel as bad about it as Maren did.” She compliments Khadijah’s skin rapturously, but also “was confused about whether I was supposed to let Khadijah know that I knew she was black or if I was supposed to pretend that her blackness never crossed my mind.” This kind of discomfort expresses itself in the form of microaggressions. Everybody at the Richual office calls each other babe, Khadijah notes, but she was “only ever Khadijah.”

Amid all this multivalent offensiveness, Stein throws in some stark truths, like the fact that all this controversy might, in the long term, be good for the paradigmatically canceled feminist founder. On a very early page, Maren observes, “The worse it gets—I mean the more women who are outraged and terrified and suffering—the more our user base grows. The more the network scales.” Although Self Care flits around themes from friendship to rape to eating disorders, it is ultimately a story about rapacious capitalism.

Self Care proves Leigh Stein’s status as a great “demolition expert” (Kenneth Tynan’s term for Bernard Shaw) of the influencer era. “We are being grossly irrelevant,” Tynan wrote, “if we ask a demolition expert, when his work is done: ‘But what have you created?’” This is often the rejoinder made by corporate feminists to their dissenters—what have you ever done, except try to take me down?—but Stein’s response is simple: She made a different kind of mirror.