Diagnosing Donald Trump with any number of psychological defects has become an armchair sport. Despite guidelines prohibiting psychiatrists from diagnosing patients they have not personally examined, many in the mental health field have gotten in on the action. They have said Trump has narcissistic personality disorder, malignant narcissism, a profound lack of empathy. Others have theorized that Trump is incapacitated by drug addiction, dementia, or even syphilis. But even though the wall between the president and the people has never been thinner—creating a situation in which Trump perpetually seems to be on the proverbial couch—these diagnoses are inevitably hampered by speculation.

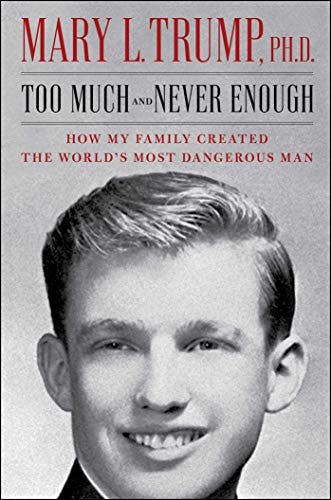

Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man presents itself as the first genuine psychological portrait of Trump by a person who knows him well. It is written by the president’s niece, Mary L. Trump, who not only has the firsthand experience with the president and his family that his would-be shrinks lack, but is also herself a clinical psychologist by training.

And Mary is not shy about diagnosing her uncle. Too Much and Never Enough is full of explanations for Trump’s behavior: abandonment issues, narcissism (a common theme in these psychological explorations), stunted emotional growth, caffeine dependence. All of these have combined to form a 74-year-old toddler who just happens to be the most powerful person on the planet.

Of course, we don’t need an expert to tell us that Donald Trump is a badly damaged individual. So it helps that Too Much and Never Enough also functions as a story of revenge, not just on the president but on his entire family.

Based on conversations with Trump’s siblings, Mary reveals that the president’s early life was defined by neglect and psychological abuse. The kids were raised by an absent and often ill mother and a megalomaniacal, cruel father. Although the Trump children each suffered in unique ways, they had many afflictions in common: insecurity, difficulty in relating to others, an all-consuming fixation on money, which is confused with worth.

The women of the house—the matriarch Mary Trump and her daughters, Maryanne and Elizabeth—were confined to gender roles that were rigid even for the 1950s. The three boys—Fred Jr., Donald, and Robert—had to fend for themselves in an environment not unlike The Lord of the Flies. Enamored with the prosperity gospel, Fred Trump Sr. drilled a ruthless code into his sons: Do whatever it takes to get ahead. Emotion of any kind was weakness. Lying, cheating, stealing—all encouraged.

Crushed by his overbearing father, Fred Jr. left the family business to follow his passion, joining TWA as a pilot. His father, furious that one of his children should deign to leave his shadow, belittled him endlessly, comparing him to a “bus driver.” Fred Jr. turned to alcohol, lost his job, and returned to the family business. It wasn’t long before he lost everything: His wife left him, taking their young children, including Mary. He died, age 42, living in his parent’s attic. It is strongly suggested that, in a final act of neglect, his parents for weeks ignored signs that he was on the verge of death before he was ultimately stricken with a fatal heart attack.

When Fred Sr. died, Mary and her brother discovered they had been cut out of the will—almost as if their father had never existed at all—provoking a lengthy and bitter legal fight with the patriarch’s four surviving children. (As a negotiating ploy, the four Trump children kicked Mary, her brother, and their families—including a toddler with severe epilepsy—off the family’s health insurance plan.)

Donald was the one Trump child who lived up to Fred Sr.’s expectations (he would also be the only one Fred Sr. would remember when suffering, late in life, from dementia). While the other Trump children gained little from their extremely wealthy father for most of his life (Maryanne, who became a federal judge, at one point was reduced to begging her mother for spare change), Donald was endlessly rewarded for his mendacity and aggression in the rough-and-tumble world of New York real estate. Fred Sr. showered his son with money, allowing him to create the illusion that he was self-made, a brilliant dealmaker. This phony personal brand would be the foundation of Donald’s successful presidential campaign.

But Donald, in Mary’s telling, was the most wounded of the Trump children. He was also the most pathetic. He became profoundly needy as a result of childhood neglect but lacked the means of processing his emotions. He got stuck in an endless feedback loop of self-aggrandizement and self-loathing, seeking out sycophants to assure him that he really was great—even though, deep down, he knew he was unloved and incapable of executing even the most basic tasks.

All of this is apparent to anyone who has observed Trump closely (or even not so closely) these past few years. Trump’s daddy issues are nothing new. Despite Mary’s insistence that the media has failed to cover the issues she writes about in this book, the truth is that no political figure in modern history has received more negative attention or had more obvious flaws. Mary can twist the knife in describing Trump’s insecurities—describing him as someone who “knows he has never been loved”—but this is not a book that will likely change anyone’s mind about the character of the president.

But perhaps the American public isn’t the intended audience. The people in Trump’s orbit have long been accused of performing for an “audience of one.” Too Much and Never Enough appears to have been written for an audience of four: Donald, but also his three surviving siblings. For Mary, these siblings have, for too long, escaped the consequences of supporting their horrible brother.

Those revelations have likely already torn a hole in the family. (Much of the most salacious information in the book evidently comes from Maryanne. Although she is thanked in the acknowledgments, it is not clear that she knew the things she told her niece about her upbringing, her father, and her brother would ever be made public.) And there’s more: Late in the book, Mary reveals herself as a key source in The New York Times investigation that showed Donald’s lifelong dependence on his father’s wealth, as well as extraordinary financial fraud committed by every member of the Trump family. Mary provided the Times with documents she obtained while contesting Fred Sr.’s will.

That story, and the investigations it spawned, have profoundly affected the Trump family. They led, among other things, to Maryanne’s retirement as a federal judge and may ultimately result in future legal and financial consequences. The revelations in Too Much and Never Enough may not change our picture of the president much, but they’ve certainly unnerved him and his siblings. That counts for something.