In his book The Crisis of the Middle-Class Constitution, legal scholar and public policy analyst Ganesh Sitaraman writes the following: “When it is used today, ‘progressive’ is not usually thought of as describing someone with a coherent worldview or philosophy. Instead, it is generally thought of as a term to describe those who prefer not to be called ‘liberal,’ those who are on the far left side of the political spectrum, or those who are part of a conglomeration of center-left groups in American politics.”

Sitaraman is telling us the word progressive, which has become virtually ubiquitous in contemporary American political discourse, is effectively meaningless: A word that carries several different and conflicting meanings has, essentially, no real meaning. When I once argued this point to someone who heads up an organization with the word progressive in its title, he replied, “Yes, that’s the beauty of it! You can make it mean anything you want it to mean.”

The word progressive, which had lain dormant in American politics for several decades, was revived in the 1980s as a synonym for liberal, after Ronald Reagan’s incessant derision of the term rendered liberals terrified to use it. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, people who previously might have been proud to call themselves “radicals” suddenly became soi-disant progressives as well. Generally left-leaning people whose politics were either amorphous or polymorphous appropriated the adjective, too.

Surely, however, it’s long past time for an American left to get serious about the meaning of the word its members routinely use to describe themselves. A good place to start looking for the meaning—the true and original meaning—of that term is in journalist Dan Kaufman’s book The Fall of Wisconsin. It recounts how Republican Governor Scott Walker waged a systematic and highly successful campaign to undermine the political reforms achieved in Wisconsin in the early twentieth century under the auspices of the original Progressive Movement. In order to tell that story, however, Kaufman needed to explain what the Progressive Movement in Wisconsin was all about.

Wisconsin’s foremost Progressive leader was the great Robert La Follette, who served the state as congressman, governor, and U.S. senator. La Follette built a veritable political machine in Wisconsin; at its foundation were the state’s numerous Scandinavian immigrant communities. The state’s Scandinavian immigrants, Kaufman explains, shared a value system that was both egalitarian and communitarian in essence—one that led them to establish agricultural cooperatives among themselves and strongly support Wisconsin’s nascent labor union movement, together with public institutions like the state university. Walker, as governor, effectively destroyed Wisconsin’s private- and public-sector unions, and sought to scrap the University of Wisconsin’s mission (devised by La Follette) of serving the wider public interest as well as its individual students.

As an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin, La Follette was mentored by its then president, John Bascom, who instilled in him a dedication to public service and a sense of society “as a living thing, a type of organism,” Kaufman writes. Bascom further believed that in order “to maintain its health, the state needed to foster social, moral, and economic harmony.” Achieving the latter, of course, would require a concerted effort to drastically compress the gross inequalities of the era, one of the Progressive Movement’s foremost goals.

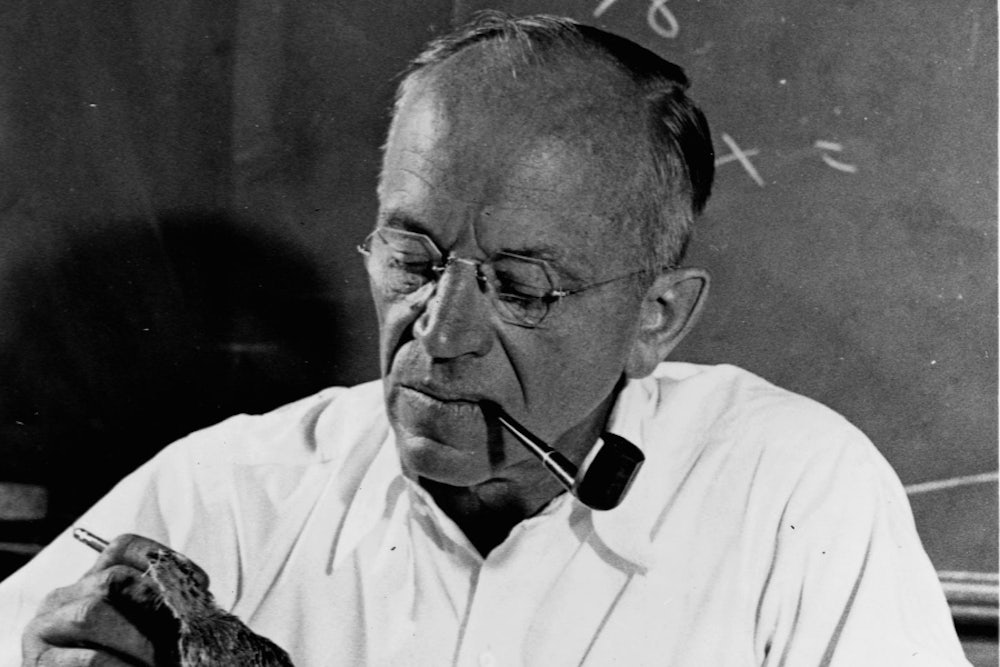

Bascom’s mentoring also supplied the basis for La Follette’s best-known legacy: the so-called Wisconsin Idea, involving the application of academic knowledge to public policy. Kaufman presents the legendary conservationist Aldo Leopold as an exemplar of the Wisconsin Idea in action. During the New Deal, Leopold, a University of Wisconsin professor of game management, oversaw the federal reclamation of the Coon Valley, a farming area in west-central Wisconsin with radically depleted soil. The initiative may have been where Leopold began to formulate his famous land ethic, which might be framed as an extension of the communitarian ideal to the natural world. “A land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it,” he wrote. “It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.” Leopold warned against the spread of industrial agriculture, with its capacity to pulverize the family farm communities of the state. His warnings went unheeded—and, quite ironically, Scott Walker was able to exploit the resulting bitterness felt throughout the farm towns of Wisconsin to get himself elected to office and destroy the state teachers’ union. Instead of focusing their ire on the factory-farming behemoths that had filched away their livelihoods, rural Wisconsinites directed their resentment toward their children’s teachers, whom they derided as time-serving public employees with cushy jobs and sumptuous retirement benefits that rural communities subsidized with their taxes, while other citizens enjoy neither job security nor generous pensions. They became Walker’s strongest base of support.

Leopold’s biographer, Curt Meine, remarked to Kaufman that he saw a balance of “self-interest and community interest” in the way Leopold died of heart failure while struggling to douse a fire on his neighbor’s land that could also have endangered his own property. Not at all coincidentally, in his new book, The Upswing (which I also discuss in this issue), Robert Putnam shows that the equilibrium between “respect for the individual and concern for the community,” which Alexis de Tocqueville defined as “self-interest, rightly understood,” was for him the cornerstone of Progressivism. The word progressive, therefore, should not be used as synonym for the term liberal, since liberalism concerns itself in the main with individual rights. Nor can it honestly be deployed as a cover for socialism, which points exclusively in the communitarian direction. To qualify as Progressive, a movement must keep individual liberty and communal liberty in balance.

Message to the American left: Let progressivism be Progressivism again.