After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a Spanish Civil War veteran from Florida named John Hovan enlisted in the Navy, serving for three and a half years before he received an honorable discharge. After the war, Hovan worked as a civilian shoe repairman at the Quonset Point Naval Air Station in Rhode Island, until one day he was abruptly fired. “This ship’s service officer came to me and said he had to tell me something,” Hovan told me in 2009. “‘Look, I’ve gotten orders to fire you, to let you go, and I can’t get any answers why.’” Hovan soon learned the reason: President Harry Truman’s Loyalty Program, an executive order that Truman signed in March 1947 to root out Communists and other “subversives” in the federal government.

Hovan, who died in 2014, was part of a contingent of American volunteers that came to be called the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. They had gone to Spain in the late 1930s to defend a left-leaning, democratically elected government from a right-wing military revolt backed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The Lincoln Brigade had been organized by the Communist Party USA and the Comintern, and Hovan, like many of the volunteers, had been a member of the party. For years after his firing, he was harassed by FBI agents. “They came to the house all the time,” he told me. “They came, too, when I was working at the textile mill. They were waiting for me out at the parking lot, trying to get me to talk.” In 1958, Hovan was subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, which had been established 20 years earlier. Asked if he was a member of the Communist Party, Hovan invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. After his testimony, a local paper ran an article headlined “John Hovan, Communist,” and his house was firebombed and painted with swastikas.

Hovan was one of nearly 3,000 workers fired between 1947 and 1956, the peak years of Truman’s order, which screened more than five million federal employees, and, in addition to the firings, pushed 12,000 people to resign. The Loyalty Program escalated the Red Scare and helped pave the way for its most notorious practitioner, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, whose life is chronicled in Larry Tye’s new biography, Demagogue. Tye, a former Boston Globe reporter, was granted access to previously sealed material from McCarthy’s archives (at Marquette University, McCarthy’s alma mater) by McCarthy’s family and to the unpublished memoirs of Jean Kerr, his widow, and Jim Juliana, a former FBI agent and McCarthy’s lead Senate investigator, by their families.

Although deeply researched, Tye’s portrait of McCarthy is highly conventional, steeped in the perspective of liberal anti-communism. A recurring theme of Demagogue is that McCarthy represents a familiar strain in American politics, on both the left and the right. Donald Trump, Tye writes, is “the latest in a bipartisan queue of fanatics and hate peddlers who have tapped into America’s deepest insecurities.” Sometimes Tye’s comparisons between McCarthy and other politicians are facile (Huey Long); sometimes they are more apt (as with Trump, his main target). But though he draws a rich, complex picture of McCarthy’s life, Tye’s emphasis on personality comes at the expense of a deeper analysis of the bipartisan tradition of anti-communism—the “long shadow” promised in the book’s subtitle. The most consequential legacy of McCarthyism is not the return of a bullying, authoritarian personality to high political office but the persistent suppression of left-leaning ideas and policies in the United States by means of red-baiting. That tradition predates McCarthy’s arrival in national politics and postdates his death, and many of the limits it imposes on our politics remain with us today.

Joe McCarthy grew up on a farm in Grand Chute, Wisconsin, a small town near Green Bay. One of seven children of Irish Catholic parents, he attended a one-room schoolhouse through eighth grade and then began working on his family’s farm. He later enrolled at a nearby high school, cramming four years of education into a single year. His ambitions and his Catholicism led him to enroll at Marquette, a Jesuit university, where he got a bachelor’s degree and a law degree in five years. In 1936, at the age of 28, he ran for district attorney in Shawano County, in northern Wisconsin, as a Democrat and a self-described “militant New Dealer.” He lost, but three years later he was elected to a circuit court judgeship. During World War II, he enlisted in the Marines, where he served as an intelligence officer and also volunteered for combat missions, sometimes as an aerial gunner on bombing missions.

In 1944, McCarthy ran for U.S. Senate as a Republican, launching his campaign while he was still in the Marines (a violation of military rules). He billed himself as “Tail-Gunner Joe” and exploited and exaggerated his military record. He lost the race in a landslide, but two years later, he ran against the Progressive legend Robert M. “Young Bob” La Follette Jr., in the Republican primary. Young Bob, a son of Wisconsin Governor and Senator Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette, and a key figure in the New Deal’s social welfare and public works programs, was running for his fifth term and barely campaigned against the tenacious and dirty McCarthy. (Another rival dropped his plans to run after McCarthy threatened to publicize his recent divorce.) McCarthy beat LaFollette by 5,000 votes. By then, Young Bob had become a vocal red-baiter, describing Communists and “fellow travelers” as “vermin” who were “infesting and polluting liberal thought,” as he wrote in an article in The Progressive, the magazine founded by his father. LaFollette’s piece, a thinly veiled attack on McCarthy’s Democratic opponent in the general election, probably helped McCarthy win a landslide victory. Young Bob wound up voting for him, too.

Initially, McCarthy expressed moderate views on the Soviet Union. “Russia does not want war and is not ready to fight one,” he said shortly after his election. “Stalin’s proposal for world disarmament is a great thing, and he must be given credit for being sincere about it.” A self-styled country rube, McCarthy resented his patrician Senate colleagues, even as he partook in the spoils (fancy restaurants, lavish gifts) of his office. Eager for attention, McCarthy attempted to gain fame in 1949, when he took up the cause of a group of Nazi war criminals—during the Battle of the Bulge, they had massacred nearly 100 American soldiers who had surrendered. McCarthy led a public campaign that alleged, baselessly, that Army investigators were acting out of vengeance. (McCarthy singled out Jewish investigators; he also referred to Jews as “sheenys” and “hebes” and called one of his staffers “useless, no good, just a miserable little Jew.”)

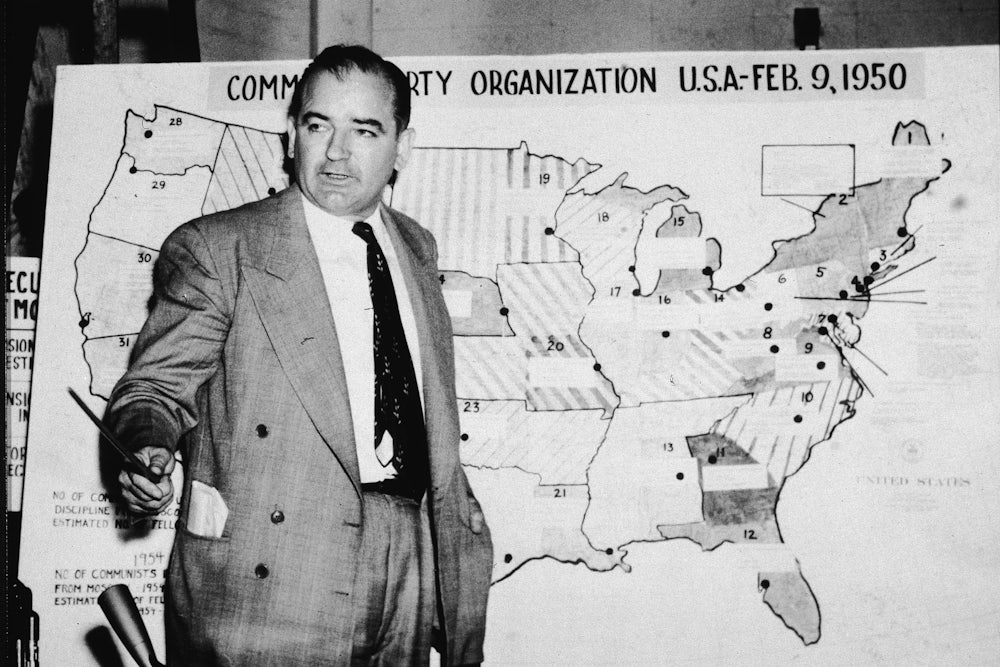

McCarthy’s defense of the war criminals won him notoriety, but few admirers. He didn’t attract positive national attention until February 1950, when he gave a Lincoln Day speech at the Women’s Republican Club of Wheeling, West Virginia. During the talk, he held up a piece of paper claiming that 205 people “were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department.” In fact, according to McCarthy’s personal secretary, the list contained only a few scribbled notes on another topic: housing for war veterans. “Joe gave us a call not too long after the speech,” William Randolph Hearst Jr., a friend of McCarthy’s, later said. “And you know what? He didn’t have a damn thing on that list. Nothing. He said, ‘My God, I’m in a jam.… I shot my mouth off. So what am I gonna do now?’”

McCarthy doubled down, embarking on an endless speaking tour across the country about the rising threat of Communist infiltration of the American government. The country was already in the throes of a moral panic over communism following the accusation that Alger Hiss, a State Department official and junior member of the U.S. delegation to Yalta, had been a Communist spy. (Hiss’s case was pursued relentlessly by an ambitious California congressman named Richard Nixon.) Despite his outright fabrications, McCarthy became an immediate sensation, constantly upping the ante until June 1951, when he accused Truman’s secretary of defense, George Marshall, a five-star Army general and the architect of the Allied military victory in World War II, of being part of “a conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man.”

Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was a friend of Marshall’s and was contemplating a run for president, said little to publicly defend him. And though privately he loathed McCarthy, Eisenhower agreed to campaign with him in Wisconsin. Fueled, in part, by the popularity of McCarthy’s Red Scare, the election turned into a Republican landslide, making Eisenhower president and giving the party control of both houses of Congress for the first time in more than 20 years.

McCarthy became chairman of the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. He hired a vicious lawyer named Roy Cohn as his chief counsel. (For his assistant counsel, McCarthy hired Robert F. Kennedy, whom Cohn treated as a gofer.) McCarthy sent Cohn and his close friend, a wealthy Harvard grad named David Schine, to search the military’s overseas libraries for “Communist manuscripts.” That prompted the Department of Defense to remove books by Dashiell Hammett, the NAACP leader Walter White, and Jean-Paul Sartre, among other authors. Sometimes books were burned. McCarthyism contributed to an untold number of suicides, including that of McCarthy’s former political rival Young Bob LaFollette, who shot himself through the roof of his mouth rather than testify about alleged Communists on his staff in the 1930s. Though he acknowledged his father’s long bouts with depression and anxiety, Bronson La Follette, Young Bob’s son, blamed McCarthy. “My dad committed suicide instead of being called before McCarthy’s committee,” he told Tye in one of the book’s most revealing interviews. “No question at all.”

The American Civil Liberties Union and other liberal organizations, such as Americans for Democratic Action, largely caved to McCarthyism. Irving Ferman, the head of the ACLU’s Washington office, actively helped the FBI in its search for reds. In 1953, Ferman wrote a fawning letter to McCarthy, decrying “smear techniques” against the senator.

In January 1954, only 29 percent of Americans had an unfavorable view of McCarthy. Three months later, the Army-McCarthy hearings began, and they would prove to be McCarthy’s undoing. The hearings were rooted in a feud McCarthy had instigated with the U.S. Army the previous year, in which the senator alleged that Communists had infiltrated an Army base in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Shortly afterward, David Schine was drafted into the Army as a private. The Army accused Cohn of requesting special treatment for Schine, his rumored lover. McCarthy accused the military of retaliating against Schine for his investigation. Tens of millions of Americans watched the hearings, which revealed an increasingly belligerent and drunk McCarthy.

As the hearings dragged on, the public’s attention wavered, until one day in June 1954, when a frustrated McCarthy interrupted Joseph Welch, one of the Army’s lawyers, accusing one of Welch’s colleagues of belonging to an organization “long after it had been exposed as the legal arm of the Communist Party.” McCarthy’s comment broke an agreement that Welch had made with Cohn not to bring up the colleague. “Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness,” Welch said. “Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” Welch’s comment shattered the public’s perception of McCarthy. As the journalist Murray Kempton wrote, “Joe McCarthy was naked at that moment, and no man who ever clasped his hand and laughed with him could escape the sense that he had at that moment bathed himself in filth.”

In the aftermath, McCarthy was censured by the Senate, with 22 Republicans joining all of the Democrats and one independent. Shorn of his power, he was spurned by purported allies. At a campaign event for Vice President Richard Nixon at a Milwaukee hotel in 1956, McCarthy showed up uninvited, took a seat at the head table, and was promptly asked to leave. Afterward, a reporter found him in an alley, weeping. He was drinking a bottle of vodka a day then, spiking his milk with it to hide the depth of his habit from friends. He drifted deeper into paranoia, at times imagining that he was being attacked by snakes. In late April 1957, he checked into Bethesda Naval Hospital with yellowed skin from jaundice and most of his liver gone. Navy doctors listed the cause of death as hepatitis, but Tye suggests, convincingly, that McCarthy died of complications from alcohol withdrawal. He was 48 years old.

Tye’s excavation of McCarthy’s biography is exhaustive, if workmanlike. The prose is often marred by awkward descriptions (“supersonic senator”), clichés (“central casting,” “behind closed doors”), and needless details (do we really need to know the number of pages in William F. Buckley Jr. and L. Brent Bozell’s McCarthy and His Enemies?). What’s missing is a deeper examination of the anti-Communist movement.

For many historians of McCarthyism, the word itself is a telling misnomer. “It is unfortunate that McCarthyism was named teleologically from its most perfect product, rather than genetically—which would give us Trumanism,” the journalist Garry Wills once wrote, an observation that Tye notes. Ellen Schrecker, author of Many Are the Crimes, a superb history of McCarthyism, proposes a more fitting term: “Hooverism.”

In 1919, J. Edgar Hoover, then a 24-year-old Justice Department official, was appointed by the attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, to conduct a war on radicals. The Palmer Raids became the nation’s first Red Scare. Drawing on fear of the Bolshevik Revolution, anger at a wave of political bombings (including the bombing of Palmer’s house), and anti-immigrant sentiment, Hoover rounded up thousands of people and expelled many of them, including Emma Goldman. Hoover’s longevity and bureaucratic power made the Red Scare almost a constant, defined only by periods of greater or lesser intensity. As early as 1938, for example, Hoover began attacking the motives of Spanish Civil War volunteers. In a memo he wrote to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s attorney general, Homer Cummings, he proposed that the volunteers were being sent to Spain to learn “the art of military science so that they can be returned to the United States to lead the vanguard of the revolution in this country.”

Hoover was essential to McCarthy, too. He dined frequently with the senator at Harvey’s Restaurant, a Washington power lunch spot of the 1950s. Hoover supplied McCarthy with names of alleged Communists or fellow travelers, former FBI agents were lent to McCarthy as staff, and Hoover squelched rumors that McCarthy was gay. In letters to Hoover, McCarthy would sometimes cross out Edgar and write in “Boss.”

Tye often portrays McCarthy as an unserious interloper in an otherwise crucial endeavor. Most of McCarthy’s Republican colleagues in the Senate, Tye writes, “had been chasing Communists long before McCarthy stumbled onto the cause, although more politely and productively.” To make that case, Tye highlights the importance of the Venona archive, a trove of decoded Soviet intelligence messages sent from Moscow to the U.S. that were declassified in the 1990s. The documents showed definitively that, during World War II, Americans working for the U.S. government had given intelligence information to the Soviets and that the Communist Party USA had provided recruits to the Soviet Union. Venona intercepts also helped investigators find Soviet spies, including Julius Rosenberg, who had worked for the Army Signal Corps from 1940 to 1945 and recruited spies for the Soviet Union from among his college classmates as well as his brother-in-law, David Greenglass, who worked on the Manhattan Project. With his wife, Ethel, Julius was tried for espionage and executed in 1953. Tye describes Venona as the “gold-standard list” of spies, and though he notes how few of the people McCarthy accused match the information in the intercepts, the documents have been used by everyone from Time to William F. Buckley Jr. to burnish McCarthy’s image.

What Tye does not address is the questions raised by left-leaning historians about the reliability and significance of the Venona intercepts. In a 1999 article in The Nation, Walter and Miriam Schneir, who wrote extensively about the Rosenbergs, detailed a 1956 memo by Alan Belmont, the FBI’s third-highest-ranking official, that urged caution about identifying specific individuals from the intercepts because they were fragmentary and full of gaps. “Some parts of the messages can never be recovered again because during the actual intercept the complete message was not obtained,” the memo said. Belmont also noted the difficulty of identifying subjects because of translation difficulties and the use of cover names. The memo concluded that proving guilt based on the intercepts would be legally difficult.

In a letter in The Nation, in 2000, Ellen Schrecker and Maurice Isserman, a historian of communism in the U.S., argued that it was important to consider the fact that most American spying for the Soviet Union took place during World War II, when the countries were allies. (Desperate for more assistance from the U.S. and Great Britain, the USSR was absorbing the onslaught of the Nazi war machine: The Soviet Union took 95 percent of the casualties of the three Allied countries and inflicted 70 percent of the German casualties.) Schrecker and Isserman wondered, too, if the U.S. would itself have developed the bomb as quickly as it did had McCarthyism been applied to J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the Manhattan Project, whose wife, girlfriend, and brother had all been Communists.

At times, Tye engages in sloppy, reductive thinking about the left—as when he argues that the sentiments fueling the Red Scare were rooted in an essential American ethos. “The loathing came naturally,” Tye writes. “Egalitarianism, democratic socialism, class struggle, and other founding precepts of communism and Marxism were the antitheses of democracy’s and capitalism’s free markets, multiple parties, and individualism.” Tye fails to mention that Milwaukee, the largest city in McCarthy’s own state, was efficiently governed by democratic socialist mayors for nearly 40 years between 1910 and 1960. The last of these mayors, Frank Zeidler, won his second of three terms in 1952, the banner year for McCarthy and the Red Scare.

Tye acknowledges that anti-Communists could be overzealous. “Early anti-Communists insisted they were defending democratic values, and sometimes they were; just as often they were attacking what seemed foreign,” he writes. “Nuance was lost and irrational connections followed—that Communist meant Stalinist, and that all party members and fellow travelers must be spies and anarchists.” But his fixation on Soviet crimes—espionage, Stalin’s monstrous killings—comes at the cost of a more balanced treatment of the role Communists have played in America’s political history, especially in regard to racial justice.

Besides risking their lives to fight fascism years before Pearl Harbor, the Lincoln Brigade was completely integrated, a decade before Truman’s order to desegregate the U.S. military. Moreover, in July 1937, Oliver Law, an African American Communist and union organizer from Chicago, was chosen by white officers to lead the brigade, becoming the first Black officer in American history to command white soldiers in battle. (Law was killed soon afterward, outside Madrid.)

The Communist Party USA played a courageous role in organizing Black workers and farmers in the South, particularly in Alabama from the late 1920s to the early 1950s. It was responsible for drawing national attention to the case of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African American teenagers falsely accused of raping two white women, and the party’s legal arm led the teenagers’ defense, even as the NAACP initially balked at supporting their case. As the historians Robin D.G. Kelley and Mary Stanton have shown, the party was remarkably successful at organizing Alabama’s impoverished Black sharecroppers. Sometimes Communist organizers managed to bring working-class people together across racial lines, even at the height of Jim Crow. In 1932, Angelo Herndon, an African American laborer who had joined the Communist Party in Alabama, helped several hundred unemployed workers, Black and white, stage a protest at a courthouse in Atlanta. Herndon was arrested less than two weeks later for insurrection. “We were called comrades without condescension or patronage,” Herndon wrote of communism’s appeal to African Americans like himself. “We were treated like equals and brothers.”

While Tye faithfully addresses the dark side of communism, he does not sufficiently grapple with the dark history of anti-communism, both abroad and in the U.S. Take Spain, for example, where Angelo Herndon’s brother, Milton, a member of the Lincoln Brigade, was killed in battle in 1937. The following year, John Hovan and the other international volunteers were sent home by the faltering Spanish Republic in a futile attempt to persuade Hitler and Mussolini to also withdraw their troops. But on April 1, 1939, General Francisco Franco, the leader of the military revolt, declared victory, and that same day the U.S. recognized Franco’s government. What followed in Spain was a four-decade-long far-right dictatorship that executed tens of thousands of people and sent more than a million political prisoners to concentration camps, jails, or forced labor battalions. Despite this brutal record, Franco remained a staunch anti-Communist ally of the U.S. In the following decades, anti-communism in the U.S. also led to the toppling of elected foreign governments, support for military dictatorships, and the killing of untold numbers of civilians—and the damage, to countries like Guatemala, Indonesia, Vietnam, Brazil, Chile, and El Salvador, was deep and lasting.

One can only speculate what might have been, in the U.S., if it had avoided a sweeping and indiscriminate leftist purge in the postwar years, as Great Britain, Sweden, the Netherlands, and other Western European countries did. During that period, those countries and many other European nations were vastly expanding their welfare states. The U.S., by contrast, was turning rightward. In 1947, over Truman’s veto, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which required union leaders to sign loyalty oaths, pushing the labor movement to the right as it forced out many of its leftist organizers. (During the Cold War, the AFL-CIO began collaborating with the CIA to try to undermine left-wing influence in foreign trade unions.) Ellen Schrecker notes a similar purge in academia, the media, and other institutions. “All the political organizations, labor unions, and cultural groups that constituted the main institutional and ideological infrastructure of the American left simply disappeared,” she wrote. “If nothing else, McCarthyism destroyed the left.”

To Tye, who paints McCarthy as a populist, the senator’s red-baiting “was a fig-leaf for elite-bashing.” Perhaps. But it seems as likely to have been a fig leaf for something else: opposition to the redistribution of wealth. Tye hints at this other motive when he details the extent of financial support for McCarthy’s effort by powerful right-wing Texas oil tycoons, such as H.L. Hunt and Hugh Roy Cullen, who were deeply hostile to Roosevelt and the New Deal. In her biography of Alger Hiss, the journalist Susan Jacoby is more direct. Though Jacoby shares the accepted view that Hiss spied for the Soviet Union, she also notes that a major goal of the anti-Communist movement, then and now, was “undermining the legacy of the New Deal.”

McCarthyism continued to shape American politics long after McCarthy’s death. “Eleven years after McCarthy’s censure by the Senate, Lyndon Johnson would talk to his closest political aides about the McCarthy days, of how Truman lost China and then the Congress and the White House, and how, by God, Johnson was not going to be the President who lost Vietnam and then the Congress and the White House,” the journalist David Halberstam wrote. Even Medicare initially included a loyalty oath for recipients until the Justice Department conceded, in 1967, that it was unconstitutional. Two years later, Angela Davis, a newly hired professor at UCLA, came under attack by Governor Ronald Reagan and the University of California Board of Regents for being a Communist. (My uncle, Arnold Kaufman, a colleague of Davis’s at UCLA, was one of her most outspoken defenders. Firing Davis, he wrote in this magazine, “would be to violate any conception of academic freedom one claims to be defending.”)

One could argue McCarthyism’s hold on the American psyche continues to this day. Trump declared during his State of the Union address last year that “America will never be a socialist country.” Republicans and Democrats alike, including Senator Elizabeth Warren, stood up and applauded Trump’s comment. The image of Bernie Sanders, the Senate’s only democratic socialist, remaining seated was even more striking. Despite Sanders’s 40 years as an elected official and his social democratic policy agenda of universal health insurance, free college education, and increased public investment, all of which are mainstream positions throughout Europe, he is routinely red-baited. (Harvey Klehr, for example, an emeritus professor of history at Emory University and one of Tye’s primary sources, who is given a special acknowledgment, wrote an article in April called “Bernie Sanders, the Tyrants’ Friend,” which described Sanders as “a far-left fellow traveller with some very murky associates.”)

Even though Sanders lost the Democratic primary, Trump is still running against him. “Biden is a Trojan horse for socialism,” Trump said in his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention in August. “If Joe Biden doesn’t have the strength to stand up to wild-eyed Marxists like Bernie Sanders … then how is he going to stand up for you?” Though Biden has repeatedly disavowed any connection to socialism, Trump’s accusation and Biden’s defensive response bring to mind the words of Truman, who both acceded to the demands of the anti-Communist movement and understood the power of red-baiting as a cudgel for the right. “Socialism is a scare word,” Truman said in 1952. “Socialism is their name for almost anything that helps all the people.”

For all the similarities Tye lays out between Trump and McCarthy—their temperament, their mendacity, their corruption, their admiration for Roy Cohn—what goes unmentioned is their shared affinity for red-baiting, the most ubiquitous remnant of McCarthyism. That tactic, regrettably, continues to be embraced by demagogues and nondemagogues alike.