Thomas Wilner is like any other semiretired person living amid the palm trees in Florida. A lawyer at the giant firm Shearman & Sterling, he returns to Washington, D.C., once a month for a few days to visit the office. But he no longer works any big international cases of the sort that were once his specialty—litigation or trade and policy efforts for foreign governments such as Kuwait and Mexico. At age 77, he now spends much of his time walking, biking, and occasionally golfing. His granddaughter just turned 18, and he is looking forward to seeing her off to college next year.

The only difference between Wilner and the other septuagenarians who have migrated south for their golden years is that he invests energy working pro bono on the legal cause in which he’s been active for two decades: closing the lawless military prison at Guantánamo Bay. Long after most other Americans have forgotten about its continued existence, Wilner keeps working to excise what he calls a “cancerous boil on our nation’s skin that has got to be removed.” He fears the prison may outlast him. “I don’t know when I’m going to die,” he said, “but I don’t want to die with this still there.”

In addition to working through the courts, Wilner operates the website closeguantanamo.org with Andy Worthington, a 59-year-old British investigative journalist. “I can’t quite remember who came up with the idea of the ‘close Guantánamo’ campaign,” Worthington said. “Between us it happened anyway.” The website, started in 2012, profiles current and past detainees with articles, interviews, and photographs; includes news updates; and suggests ways readers can get involved in activism. Wilner and Worthington continue to advocate for the 37 remaining inmates at the prison, which will have its dismal 7,500-day anniversary of operations in July. They participated in an online event at the D.C.-based think tank New America in January, marking Guantánamo’s 20-year anniversary, and they send out newsletters once or twice a month.

But truth be told, it’s harder to get a hearing with the public than it used to be. “There was a time, back in 2003, 2004 through 2008, I must have had 15 to 20 editorials published in The [Washington] Post, The [New York] Times, The Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times,” Wilner recalled. “I can’t get anything published now.” Recently, an editor at the Post told Wilner candidly that the paper has “Guantánamo fatigue.” She could have been speaking for most of the media, which has omitted the U.S. naval base from its preferred coverage areas. There are important exceptions, most notably with The New York Times, where journalist Carol Rosenberg reports on court proceedings, prison personnel developments, and policy changes. But the ongoing civil liberties catastrophe that is Guantánamo Bay is mostly unimportant for the editors, bookers, and producers who make decisions in newsrooms and television and radio studios around the country.

To be fair, their apathy only reflects the sentiments of the American public. Citizens are placing virtually no pressure on elected officials to shutter the prison and release its inmates. Those pushing for official apologies and reparations from the federal government for its 20 years of violations are even fewer in number. Even at its most popular, the campaign to close Guantánamo Bay never received majority support in the United States. But at least it was a topic of discussion. Now the effort to end the Kafkaesque facility 500 miles south of Florida has largely been left to Wilner and Worthington, two men who never really wanted that job.

The “worst of the worst,” Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld called the people held at the prison in 2002. But in fact, a declassified memo Rumsfeld wrote showed that he knew that the detainees filling up Guantánamo Bay were, as he put it, “low-level enemy combatants.” The memo said the camp served as “a prison for Afghanistan.”

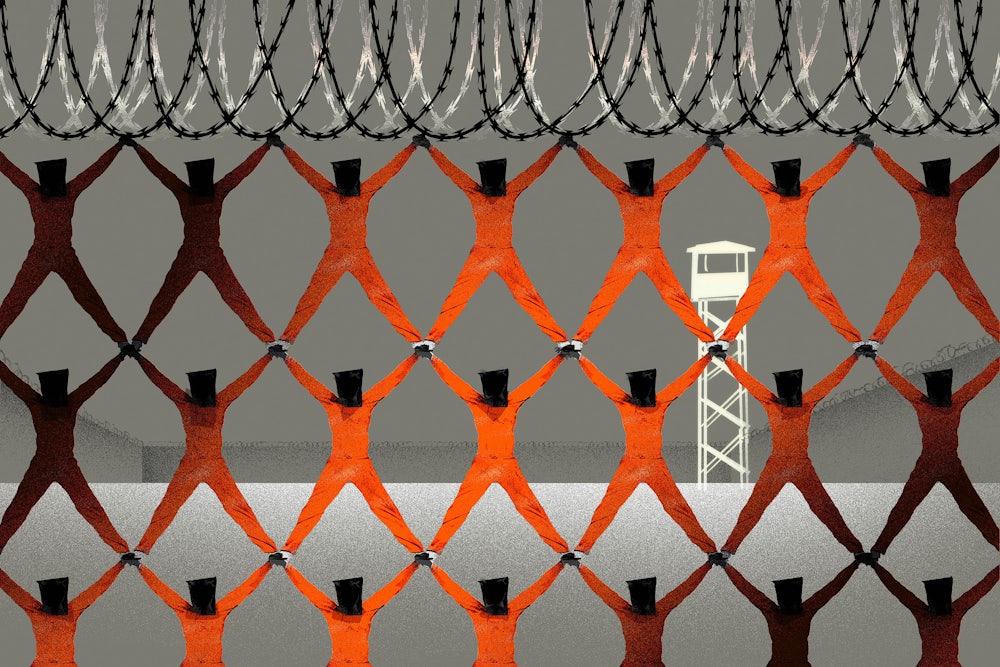

At this prison, torture was rampant, with the identities and numbers of individuals held kept secret. The George W. Bush administration’s lawyers declared the camp to be outside America’s legal jurisdiction, since it’s on the Cuban landmass. That was their rationalization for insisting that the rights inmates enjoy at prisons on U.S. soil—such as a fair hearing in court—didn’t necessarily apply at Guantánamo. The Justice Department also determined that detainees were not entitled to the rights contained in the Geneva Conventions, deeming them unlawful combatants. Bush’s team essentially declared the men in its custody to be nonpersons.

Ever since, civil liberties advocates have worked to counter GTMO, as it came to be called. But Wilner wasn’t among the original critics. A longtime Washingtonian, he saw the photos of men in orange jumpsuits that splashed around newspaper pages in January 2002 and was grateful that the 9/11 terrorists had been caught. But in March of that year, a headhunter working for some Kuwaiti families asked if he would represent them. Their sons were missing, and they thought Wilner could help determine if the United States was holding them. The families insisted on paying him, so his firm donated all the fees to a 9/11 charity. They also made an agreement—if one of the men held turned out to be a terrorist, Wilner could drop the case. “I’m not a guy who would defend anyone—I would not defend [senior Al Qaeda leader] Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. I don’t want to use my talents to get a guy who is really guilty a better deal,” he told me in April, speaking on a Zoom call from Florida.

Wilner met with the families in Kuwait, visited Amnesty International, and “learned more information that a lot of these people really may not be the right guys,” as he later put it. He discovered that bounties were being offered in Arab and Muslim countries to anyone who turned over individuals to the United States, even if evidence of any wrongdoing was scant. Such a process was a recipe for abuse. Wilner and his team filed a lawsuit demanding fundamental due process rights for his clients. The right to have lawyers, hear evidence against you and challenge it, have contact with your family, get a fair hearing—these elementary human rights were denied to the nearly 800 individuals total who were taken to GTMO at one time or another.

Wilner became obsessed with the case, the fundamental un-American nature of the prison, and the public’s compliance, if not outright support, for its illiberalism. In June 2004, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Wilner’s clients had due process rights. “I thought we’d won, everyone thought we’d won,” he recalled. He assumed everyone at GTMO would finally get a fair hearing, even if it meant some detainees would remain there because they were indeed terrorists. But the government argued that the prisoners were not entitled to constitutional protections because they were foreigners outside the United States. Wilner returned to court to argue that constitutional rights weren’t required to merit due process.

Meanwhile, in 2006, a successful lawsuit filed by the Associated Press uncovered thousands of pages of government documents relating to GTMO. Andy Worthington was then a freelancer in London, writing books about Stonehenge and protests at the ancient monuments. His work familiarized him with court rulings and the judicial system. When the AP published the documents, Worthington figured that reporters at a prominent U.S. newspaper would use them to identify the detainees’ identities. But that didn’t happen, and he realized he knew how to do it. He approached a left-wing publisher in the U.K. and spent the next 14 months establishing who exactly was at GTMO. “I was able to work out that nobody was actually captured on the battlefield,” he said. Most detainees were just fleeing the chaos that was Afghanistan in late 2001 and early 2002. Some were bad guys, but few were high-level terrorists.

Worthington’s 2007 book, The Guantánamo Files, was the first to name all the names. He began working on a documentary film about GTMO, and Wilner was one of his talking heads. They became fast friends. Both were excited about Barack Obama’s presidential election victory in 2008, which came on the heels of the Supreme Court’s ruling supporting Wilner’s case that detainees had the constitutional right to challenge their status in U.S. courts. “It had become politically toxic at the time of the Obama-McCain challenge. It really was in the news,” Worthington recalled. As Wilner put it, “It became a chic thing to criticize Guantánamo.” Thomas Friedman of The New York Times called GTMO “the anti-Statue of Liberty.”

Wilner said he had met with Obama’s advisers and used his Senate office as a gathering place to strategize on lobbying Congress to reverse legislation hostile to the detainees. Obama campaigned boldly on closing the base. Even Republican presidential nominee John McCain supported closing GTMO at that time, but he lost to his even more anti-GTMO rival.

Bush had released 533 prisoners during his tenure, and about 240 remained when Obama took office. Among Obama’s first executive actions as president were banning the use of torture and ordering GTMO’s closure within one year. Wilner took heart from his successes—all the Kuwaitis were released, so he took on other GTMO members as clients. The end finally seemed near. “I thought we had it closed,” Wilner said.

But Obama’s first year came and went, and Guantánamo remained open. The president had planned to move detainees to supermax prisons and hold trials in civilian courts, but Fox News spun up its outrage machine. Soon, even some Democrats balked at the ideas of GTMO detainees being moved into prisons in their states, and Congress passed legislation barring the transfer of prisoners to the mainland United States. Within a year, Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder quickly gave up on the plan.

“He dragged his heels enormously in that first year because he really didn’t release anyone,” Worthington recalled. Obama had a list of people Bush had slated for release, but he set up a new high-level review process and delayed releasing them. “He [Obama] personally approved the imprisonment of 48 men without charge or trial. He did it—not Bush,” Worthington said. In 2012, he and Wilner started the “close Guantánamo” campaign and website, to generate media and public interest pegged to the prison’s 10-year anniversary.

But for his first six years, Obama did nothing to reduce the prison’s population significantly. It was a crushing blow. “He didn’t want to expend political capital, so he didn’t do it,” said Worthington. Wilner realized gradually that the president wasn’t going to carry out his campaign promise because the detainees had no domestic constituency demanding it—only the small population of civil liberties activists cared, and they were never a major political force.

In Obama’s final two years, he released some GTMO prisoners but stopped short of shuttering the prison entirely. In total, he released 197 detainees, leaving 41 imprisoned. Donald Trump’s election win reversed even that meager progress—he signed an executive order mandating that the facility be kept open, and released just a single inmate during his entire presidency. Obama later said that he regretted not shuttering Guantánamo Bay his first day in office. “The politics of it got tough, and people got scared by the rhetoric around it,” he said, admitting that “the path of least resistance was just to leave it open.”

That path remains attractive. During the 2020 presidential contest, GTMO was barely an issue. But President Joe Biden said he wants to close the prison by the end of this term. Having repeatedly been disappointed, however, Wilner and Worthington have trouble being optimistic about a new administration. Biden has approved more than a dozen detainees for release, but so far only three have left Cuba since he replaced Trump. Of the 37 people still held at the prison, five have never been charged with any crime and have not been recommended for release. Worthington is encouraged by letters signed by 75 House members and 24 senators urging Biden to close Guantánamo. But it is not a priority for Biden’s team any more than it was for Obama’s.

Still, Worthington and Wilner remain slightly hopeful. “With Biden, it’s become possible again” to talk about closing GTMO, Worthington said. More individuals will at least be released. But even that takes significant pressure. “It’s like squeezing blood from a particularly hard stone,” Worthington quipped. And even if every detainee were charged and/or released, there would still be the matter of paying reparations to the hundreds of innocent individuals who were held unjustly in awful conditions for years. Justice seems far off. “I’m not entirely convinced at the moment that the arc of history is taking us in anything other than quite a dark direction, to be honest,” said Worthington.

Even for the sunniest activist, spending two decades on an unpopular campaign to close a brutal human rights abomination can be difficult. “I do get tired,” Worthington admitted. Wilner has sometimes asked himself why he continues with his efforts when he could be enjoying Florida without bothering to help some people most of the country ignores or despises. “This is horrible, it’s a great injustice,” Wilner said. His anger spurs him to continue the campaign to close Guantánamo, even while other advocates have moved on. “I can’t let it go.”