The great, early-twentieth-century Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy much preferred writing about a culture’s end-times rather than all of the times that came before. This was largely because he preferred reflecting on past achievements to enduring the vicissitudes of producing or maintaining new ones. His short, abrupt, almost parable-like lyrics of historical figures and events—such as “The God Abandons Antony” or “Thermopylae”—don’t feature strong men achieving victories that will, after death, immortalize them but rather describe the slow, inevitable acceptance of whatever defeats may come next.

In “Thermopylae,” the central event is not a small, heroic band of Spartans standing against the uncountable Persian hordes; it’s about the “honor” that “still is due to them / when they foresee … /… that the Medes will eventually break through.” In much the same way, Cavafy’s personal poems often concern men growing old as they reflect on shimmering, partially recalled passions, as in “Since Nine—” when one of his many aging monologists sits alone in his dimly lit house recalling:

The apparition of my body in its youth,

since nine o’clock when I first turned up the lamp,

has come and found me and reminded me

of shuttered perfumed rooms

and of pleasure spent—what wanton pleasure!

As the late Hellenistic scholar Peter Mackridge wrote, in his introduction to an Oxford collection of Cavafy’s poems, Cavafy was “often called a ‘poet of old age,’” but that statement might easily be rewritten to say he was a poet of “old age and old, half-remembered achievements.” Unlike his contemporary and admirer T.S. Eliot, he didn’t see history as ending “with a whimper” but rather with a long, subsiding, pleasurable sigh of recollection. For Cavafy, when life and history came close to their ending, poetry began.

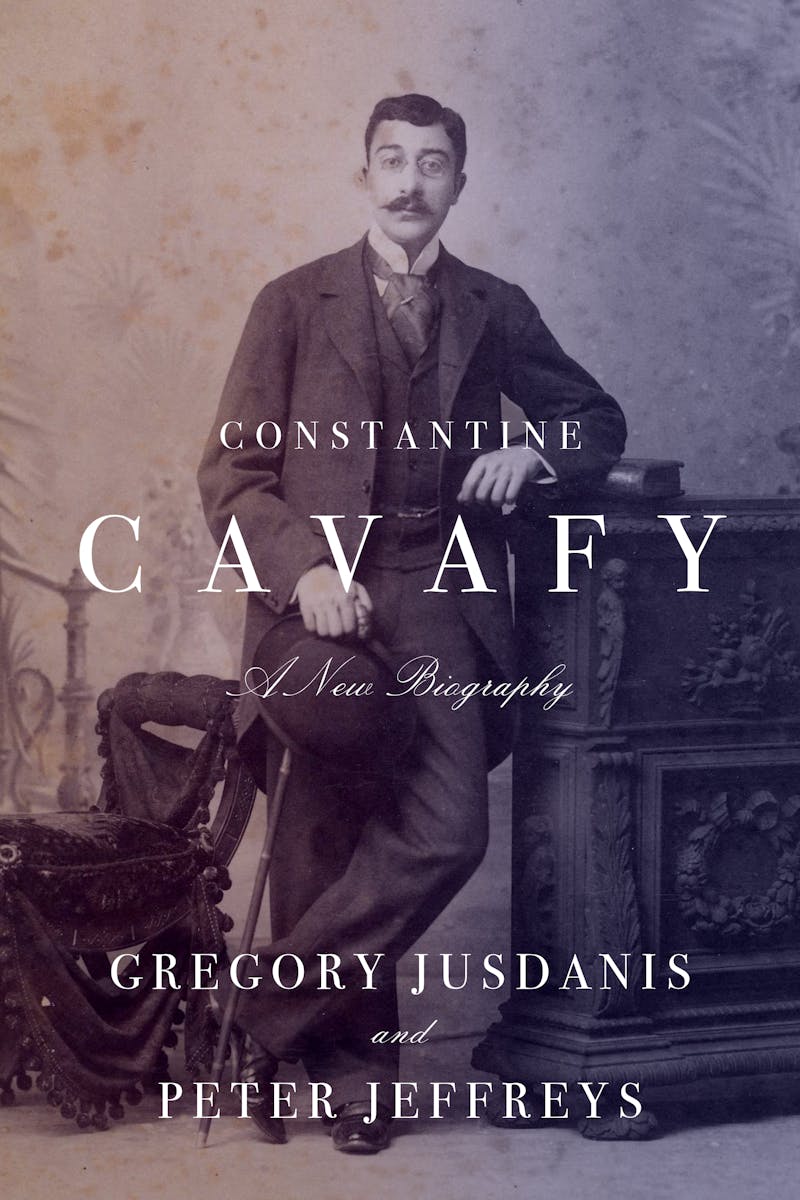

It’s probably a good time to read (or reread) Cavafy, a poet who lived in an era similarly turbulent to our own but who always found time to indulge himself with the less turbulent and (for him) more lasting pleasures of poetry. In Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography, Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys have taken many liberties with the normal chronological structure of narrative storytelling, and mostly it pays off. Structured thematically—which sometimes means the reader gets a bit lost in the often sedate, expanding uneventfulness of Cavafy’s life—the book features long chapters focusing on distinct aspects of the poet’s life and work: His relationship with family members comprises one chapter, while social relationships with other hedonistic, spoiled young men like Cavafy himself comprise another. And there’s one long, fascinating section that simply details a normal day of Cavafy’s rambles through Alexandria. In many ways, the authors seem to have found the perfect “form” for presenting the complex figure of Cavafy—a relatively solitary and self-determined man who intersected with the events of his time and the people in his life, while still establishing his own sense of time and history in a series of unique poetic reflections. He never seemed to achieve great things or earn literary fame so much as steadily generate, and enjoy, books and streets and poetry and lovers and friends. He lived his life, just as he wrote his poems, like a series of sweet secrets.

Cavafy was born in Alexandria in 1863, the youngest of seven brothers; his family “was above all else defined by a Victorian mercantile ethos stemming largely from the network of the Anglo-Greek community that operated out of Manchester, Liverpool, and London,” according to Jusdanis and Jeffreys. And from a young age, Cavafy grew accustomed to having empires vanish under his feet. His father died when he was still a child; a subsequent worldwide depression (1873) dismantled the family business; and various political conflicts (such as the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882), sent Cavafy and his family scurrying from Liverpool to Constantinople and back, until Cavafy, with his devoted mother, Heracleia, settled permanently in his hometown of Alexandria, where he spent the remainder of his life. Cavafy wasn’t the type of young man born to wrest his family from economic misfortune; spoiled and dandyish, he preferred hanging around cafés, bars, and brothels, and reading books. Both Constantine and his older brother, Peter, began dabbling with poetry from a young age; but only Constantine, after many years of dilettantism, as if lifting himself up by his own aesthetic bootstraps, began to shape himself as a world-class poet by the early 1900s—and one both influential and unclassifiable in equal measure. His work (also collected in a two-volume English translation by Daniel Mendelssohn in 2012) seems to have been deeply significant to the reading lives of his contemporaries—such as W.H. Auden, Eliot, and D.J. Enright—even while it is hard to find his influence in their works: Nobody ever quite wrote poems like Cavafy. Nor would they.

One of his formative intellectual influences was Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, but some of Cavafy’s deepest personal influences were the private pleasures he enjoyed with young men, whom he met during his flaneurish rambles through Alexandria. Leaving history behind is a major theme of his work, but leaving conventional daylight culture behind was the twilight pleasure he most enjoyed.

In “Waiting for the Barbarians,” for instance—perhaps his best-known work— the royalty, senators, and citizens of an unidentified kingdom prepare to surrender all their rites, finery, and institutions to an invasion of “barbarians” who will, the narrator expects, be “bored by eloquence and public speaking.” Cavafy’s poetic narratives are often like parables, rarely extending beyond 30 or 40 lines, and rather than depict history as a progress from one era to another, this one ironizes the idea of “progress,” depicting a civilization that seems readily prepared to exchange a little of what it has for a little of what it hasn’t—much like Cavafy’s wandering lovers, moving through the streets and markets of Alexandria from one affair to another. As the nameless narrator (most of Cavafy’s narrators lack names, ages, or physical details) concludes:

And now, what will become of us without barbarians.

Those people were a solution of a sort.

But Cavafy’s monologists never really achieve “solutions.” If they’re lucky, they move on from one interesting experience to another, and after many years, those experiences add to their rich storehouse of remembrances. Just as the narrator of “Ithaca” advises an unnamed, Odysseus-like figure: “Do not hurry your trip in any way. / Better that it last for many years; / that you drop anchor at the island an old man, / rich with all you’ve gotten on the way.” Cavafy’s sense of history isn’t ruled by heroes and kings; rather, it is an empire of memories established in the hearts of old men.

For Cavafy, life and poetry were entirely cut off from the conventional arcs of everyday life—working regular jobs, making money, and raising families. As a young man he managed to acquire a government job at the Department of Irrigation Service that didn’t make many demands on his attention and sent him home early every afternoon to think about nothing but his poems. Even his method of publishing and promoting his work was more of a closet industry than a writerly vocation; when he had enough poems (most of which he would work over for many years until he deemed them satisfactory), Cavafy would print them as broadsides at his own expense and distribute them freely to friends and families who, in turn, were expected to pass them on. Eventually, through these networks, Cavafy distributed small volumes of his collected poems, again at his own expense. Yet despite these slim beginnings, there was something about Cavafy’s work—and his personality—that eventually drew admirers from all over the world, many of whom journeyed to Alexandria to visit his home and share café meals and conversation—including writers such as Nikos Kazantzakis and E.M. Forster. Forster met Cavafy in 1916 and spent the next several years promoting his work in essays and by making personal introductions to the likes of T.E. Lawrence, T.S. Eliot, and Cavafy’s eventual English-language publisher, Leonard Woolf at Hogarth Press. Forster also composed one of the most memorable descriptions of the poet: “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.”

Even long after his death in 1933, Cavafy’s spirit haunted most modern literary visions of Alexandria, and it even circulates throughout Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet, where Cavafy is referred to simply as “the old poet of the city,” as if there could be any other.

The later Greek poet, George Seferis, famously claimed: “Outside his poetry, Cavafy does not exist.” And it’s hard to think of another poet whose entire life was so devoted to, and even subsumed by, the written word: When Cavafy wasn’t writing, he was either reading or talking to friends about what he was writing and reading.

Cavafy was probably the least naturalistic poet of his generation—and while he shares some affinities with the symbolists, such as Ezra Pound and Paul Verlaine (two of his admitted major influences were Verlaine and Charles Baudelaire), his poems seem more anchored in basic human realities than theirs. Even when his poems focus on historic events—the assassination of Julius Caesar, say, or the contentious satrapies that succeeded Alexander the Great—the language is so simple, and the characters so generalized, that they read almost like a series of floating, disconnected memories of men that somehow persisted long after their bodies turned to dust. (Cavafy almost never wrote from the viewpoints of women.)

As Jusdanis and Jeffreys argue, Cavafy’s poems rarely examined the specific world he visited in his ramblings through Alexandria; what interested him more was the aesthetic world he fashioned from them. It’s hard to think of another poet who, like Cavafy, could spend a lifetime strolling by his home city’s port-side bars and restaurants and yet only once mention the ocean as a subject—“and then only as an absence”—as he does in “Morning Sea” (1916).

Here let me stop. Let me too look at Nature for a while.

The morning sea and cloudless sky

A brilliant blue, the yellow shore; all

Beautiful and grand in the light.Here let me stop. Let me fool myself: that these are what I see

(I really saw them for a moment when I first stopped)

instead of seeing, even here, my fantasies,

my recollections, the ikons of pleasure.

Unlike the romantics, Cavafy is not drawn into the awesomeness of mountains and valleys; rather, he is quick to turn his eyes from them, preferring to wander absorbedly in the memories and impressions that nature has invoked, and always returning to the subjective realm where only he, Cavafy, reigned supreme. He might briefly appreciate nature’s beauties, but those visions are quickly supplanted by his “fantasies,” “recollections,” and “ikons of pleasure.”

There is something deeply self-absorbed and even solipsistic about Cavafy, and everything about his life seemed like a monument to itself. As Jusdanis and Jeffreys make clear, his apartment was both a writerly retreat and a monument to hoarding: He seemed incapable of throwing out anything that related, however incidentally, to any event or memory from his past—letters, photographs, books, recipes, printed menus, train tickets, receipts from hotels, inventories he kept of games he enjoyed playing (dominoes, roulette, tombola), and even his mother’s jewelry.

According to some friends, Cavafy’s sexual rambles continued well into old age, and while he was more forthcoming about his sexuality than, say, his contemporary, Wilfred Owen, he was not gregarious about relating his amorous adventures. In one poem, “That They Come—,” he describes that part of his life that was never a secret but was never brought forth shining into the daylight, either:

One candle is enough. Its faint light

is more fitting, will be more winsome

when come Love’s— when its Shadows come.One candle is enough. Tonight the room

can’t have too much light. In reverie complete,

and in suggestion’s power, and with that little light—

in that reverie: thus will I dream a vision

that there come Love’s— that its Shadows come.

In Cavafy, the need for light is almost incidental; it only marks a space in the darkness where an individual can “dream a vision” and, with a single candle, energized by reverie, make the room “complete.”

This is the first major biography in English since Robert Liddell’s in 1974, and it is a much more substantial and devoted work than that previous one; it also comes at a time when poets as idiosyncratic as Cavafy might be easily forgotten for a variety of reasons. For while many different “schools” of critical attention have sought to appropriate Cavafy’s work and life, it is never possible to reduce him to the dimensions of either a “gay” poet or a “Greek” poet, a modernist or a symbolist. And in his preference for Hellenic Greece rather than the golden age of Athens, he treated the dispersion of Greek arts and literature after the Roman Empire as more significant than winning wars or conquering countries.

The most fascinating chapter, though, concerns two admirers who befriended the elderly Cavafy when they were barely 20 years old—Timos Malanos and Alekos Sengopoulos. Both were brought quickly into Cavafy’s closely cultivated entourage and spent their days socializing with the poet, reading the poet, and listening to the poet explain what they were reading and why other people should read it too. Alekos—the more devoted of the pair—went on to act as the poet’s heir and literary executor after his death in 1933; the more critical one, Malanos, eventually found himself shut out of the inner circle and began writing essays about Cavafy that weren’t entirely laudatory. He wrote the first book-length assessment of Cavafy’s career, in 1971, and in one anecdote, he recalled asking the older poet to read some of his apprentice work:

He read it, then going through it line by line he kept saying, “This is Cavafian; this is not Cavafian; this parenthesis is Cavafian; this word is not Cavafian.” Naturally what was not Cavafian he changed into Cavafian.… But he himself did not see (or perhaps he did not want to see) that in this way we had a parody. His main interest was in the pupil (any pupil) who would follow his footsteps.… I was 20 years old at the time … and I sensed that his soul, concentrated all in his glance, in the touch of his hands, was about to hazard a movement in my direction like that of a carnivorous plant.

While some have dismissed Malanos’s recollections as the bitter payback of the man not chosen to be the literary executor, his anecdote communicates one of the most memorable conclusions of this latest book—that the most important person in Cavafy’s life was always Cavafy.