In the summer of 2024, Denver TV station FOX 31 was tipped off that the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua had taken over multiple apartment complexes in the nearby suburb of Aurora, Colorado. The gang-takeover narrative catapulted through right-wing media to an eager Republican presidential campaign. By October, Donald Trump had seized upon the lie—which the city’s police chief and its Republican mayor repeatedly refuted—and promised to launch “Operation Aurora,” “the largest mass deportation in American history.”

It would come out later that the buildings’ landlord, Brooklyn-based CBZ Management, had hired a P.R. team to pitch that “tip.” The truth, mundane and sinister, was that the landlord had neglected dozens of health and code violations, and that its tenants—mostly Venezuelan immigrants—had been living with roaches, bed bugs, rats, backed-up sewage, black mold, piled-up trash, and inadequate heat and hot water for years. (If FOX 31 had checked its archives, it would have found its own 2021 exposé on uninhabitable conditions at one of the CBZ properties.) Behind “Operation Aurora” was a familiar bait and switch, one that blames the conditions imposed by landlords and on tenants and substitutes law-and-order crackdowns for social support.

We should have heeded the lessons of the 1970s. Over that decade, tens of thousands of apartment buildings burned across the country in Black and brown neighborhoods hollowed out by white flight. The fires killed an estimated 500 people a year and displaced 500,000 nationwide. Families found themselves settled after one fire, only to be burned out once more. But throughout that era and even now, residents themselves were assigned the blame. Even when landlords got caught with firebombs in hand, politicians, police, and news media stuck to the talking point. Pathologizing people of color proved easier than condemning the profit motive or the racialized system of American property relations.

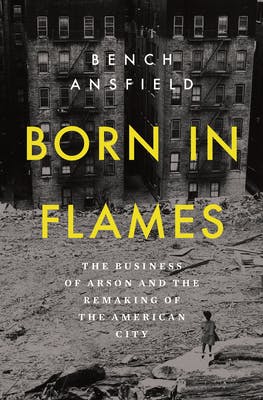

Bench Ansfield’s Born in Flames: The Business of Arson and the Remaking of the American City finally sets the record straight. How did so many apartment buildings become more profitable burned out than rented out? And how were these fires allowed to continue for more than a decade? “The evidence is unequivocal,” Ansfield contends. “The hand that torched the Bronx and scores of other cities was that of a landlord impelled by the market and guided by the state.”

Like the best crime dramas, Born in Flames manages to be both diligent and engrossing. Offering new tools to pick through this rubbled history, Ansfield grounds the arson wave in government efforts to offer insurance in Black and brown neighborhoods (as long as such efforts did not threaten existing racial hierarchies or private insurance markets), locates its material basis in insurance companies’ turn to financial investments to juice their profits, and pulls apart the bait and switch by which tenants are punished for landlords’ crimes.

We’re familiar with redlining. The real estate industry, big banks, and the federal government collaborated on home valuation schema that tethered race to risk, denied mortgages to millions of Black and brown people, and ensured most would be trapped in a captive housing market as tenants. But Ansfield’s book studies a later wave and a novel form of extractive abandonment: insurance “brownlining.” After riots erupted in almost 2,000 cities and towns in the late 1960s, Ansfield writes, “insurance personnel were, in a real sense, capitalism’s first responders,” working in an industry that aimed to convert “black resistance … into dollars and cents.” Surveying the damage, many insurance companies declared Black neighborhoods uninsurable. Riots had forced a racial reckoning—and inspired a racial panic. The federal government cut a deal with the insurance industry that reflected both: In exchange for a government backstop of reinsurance, companies would have to offer property owners in “riot-prone” areas access to Fair Access to Insurance Requirements, or FAIR, insurance plans. But these were “subprime” insurance plans—“‘back of the bus’ insurance,” in the words of one critic. They allowed insurers to charge higher monthly premiums for inferior coverage, and their exorbitant cost meant that generally only white absentee landlords could afford them. Far from a “remedy” for racist harms, FAIR plans turned racist fears into market logic.

Landlords often put this logic to work. Ansfield relates the story of Imre Oberlander and Yishai Webber, who in 1975 were among the first landlords indicted for arson conspiracy in the Bronx. When the duo were pulled over because of a broken taillight, officers discovered a pair of Hasidic men in blackface—along with two explosive devices. Ansfield suspects that to Oberlander and Webber, blackface must have seemed like its own “form of insurance.” Racism provided the cover, but FAIR plans had laid the economic kindling. One study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago suggests that in New York state, FAIR plans led to 13,000 excess fires in a single year.

Ansfield expertly spells out the incendiary impacts of “financialization” that helped these fires pencil out. When insurance companies began to invest in financial markets in the late 1960s, Ansfield explains, they got back not just more money but new incentives. They turned to “cash-flow underwriting”: prioritizing the size of their income streams to leverage as capital because there was more profit in stocks and bonds than in premiums and payouts. (Who cares about a loss on policies—$10 million in payouts to the South Bronx in just 1974—if your portfolio grows 25 percent in a year?) For insurance companies, overvaluations meant higher premiums and more money to invest. For landlords, the yawning gap between a building’s insurance valuation and its potential sale price served as an invitation to simply burn it down. Ansfield recounts the story of one landlord who paid $5,000 for a Belmont Avenue brownstone, while his insurance policy logged its worth at $250,000. To paraphrase Willy Loman in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, it was “worth more dead than alive.”

Burned-out buildings also proved valuable for constructing the politics of law and order. “The cruel irony,” writes Ansfield, “was that to survive the fires was to become their scapegoat.” Ansfield cites Democratic New York senator and Nixon adviser Daniel Patrick Moynihan throughout the book, and it’s worth revisiting Moynihan’s thinking in further depth here. Already in 1970, in his “Memorandum on the Status of Negroes,” Moynihan had warned the Nixon administration that the country was “heading for a genuinely serious fire problem in American cities,” because, he wrote, “the types of personalities which slums produce” were prone to “fire‐setting.” Moynihan claimed arson was “endemic” to Black neighborhoods, and linked fires to further “pathology.” “They come first. Crime, and the rest, follows.” While few can present it with Moynihan’s vile panache, his memorandum exemplified the dominant narratives of the arson wave: criminality and contagion.

Sensationalist media amplified these narratives. The New York Times referred to building fires as an “epidemic.” In 1973, its editorial board prophesied that the South Bronx’s “social cancer” threatened “not just the rest of the Bronx, but the city itself.” Never mind that many local property owners denied insurance had lacked resources for repairing their buildings—and that overinsured owners were incentivized to destroy them—the government, the Times argued, should give residents “an incentive … to take care of their homes—because they are theirs.”

Ansfield deftly situates the emergence of the infamous practice of “broken windows” policing within the charred landscapes and scapegoat narratives of the arson wave. The 1982 Atlantic article that revolutionized urban policing echoed both Moynihan’s slippery-slope prognosticating and the Times’ self-help scolding. To authors James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, an unrepaired broken window was an invitation, first for disorderly behavior, then for higher-order crimes. They argued police should produce a “sense of safety” in a neighborhood—a distinct goal from solving crimes—by focusing on basic order maintenance, in order to shore up residents’ capacity to police each other and themselves. “Perception is reality,” NYC’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development Commissioner Anthony Gliedman said, with a similar elision of feelings and facts. “Businesspeople make decisions based on perception.” The commissioner was explaining the Housing Department’s 1983 effort, “Occupied Look,” in which vinyl decals featuring curtains and flowerpots were installed over the Bronx’s broken windows, erecting a Potemkin village for commuters on the Cross Bronx Expressway.

Elegantly captured is the triangulation that ended the arson wave, between tenant organizations, the state, and insurance companies themselves. By 1977, it was already possible “to tell which buildings were operated by tenant groups,” as the Times reported of the South Bronx; these buildings were “usually the ones without broken windows and with heat.” From Symphony Tenants Organizing Project in the Fenway neighborhood of Boston to the Morris Heights Neighborhood Improvement Association and the People’s Development Corporation in the Bronx, tenants established associations that reclaimed buildings from absentee owners, organized night watches, and invented risk assessment algorithms, piloting many of the strategies the state would eventually adopt. The insurance industry’s fear of bad P.R. and broader regulation brought stricter underwriting standards (and a few soul-searching ads: “The profit motive built this building. It also burned it down,” went one for Travelers). But it was organized tenants—leftists who were right too soon—whose dogged persistence ensured “arson for profit” became the category of inquiry, one that placed blame beyond the “torches” who lit the fires, and even beyond the enterprising landlords who commissioned them, and onto economic incentives that inspired those actions. Like so many issues leveraged in the service of law-and-order policy, arson was ultimately a problem that police couldn’t solve; instead, as one organizer predicted, the wave would end by “pencils instead of guns.”

“The world in which a solidly built home could generate more value by ruination than habitation,” Ansfield observes, “is the same world in which homelessness, eviction, and foreclosure have become defining aspects of urban life.” Retracing the steps of past tenant victories can help guide our struggles now. While America’s fascist turn takes a real estate developer as its figurehead, the right grows its ranks by persecuting a phony enemy of real housing struggles—promoting “mass deportations” as a demand-side solution to the housing crisis—and dragging the social question of shelter beneath the banner of law and order. Surely, Zohran Mamdani’s victory in New York’s Democratic mayoral primary vindicates tenancy as a potent axis on which to forge coalitions capable of defeating rightward drift. Mamdani’s central platform—a rent freeze—galvanized New York’s tenants against their real enemies in real estate. (I helped organize a fundraiser for Mamdani this winter.) His campaign worked to reshape voters’ priorities: As he surged in the polls, the electorate’s expressed top priority flipped from crime to affordability. (The Bronx broke for former New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in the primary nonetheless.)

After Trump and national media turned away from the spectacle in Aurora, the city continued its effort to hold CBZ accountable. The Housing Department issued further rounds of violations. The city attorney filed seven criminal lawsuits. When CBZ representative Zev Baumgarten failed to appear, the court issued warrants for his arrest. But if Baumgarten never sets foot in Aurora, the case can’t continue. The city has closed three CBZ properties so far, ordering its residents to vacate. At one complex, residents were given just six days to leave. Like the Black and brown tenants who suffered through the arson wave in the Bronx, the immigrant tenants in Aurora have been made unwilling actors in revanchist political theater. Their demands for decent and secure housing have gone unheeded.