The following is a lightly edited transcript of the September 26 episode of the Daily Blast podcast. Listen to it here.

Editor’s note: After we recorded this episode, James Comey was indeed indicted, and The New York Times published additional details that expand on the reporting discussed below and reveal the prosecution as still more corrupt. Only Trump’s handpicked adviser signed on to the indictment, and career prosecutors thought the case was far too weak to justify going forward.

Greg Sargent: This is The Daily Blast from The New Republic, produced and presented by the DSR Network. I’m your host, Greg Sargent.

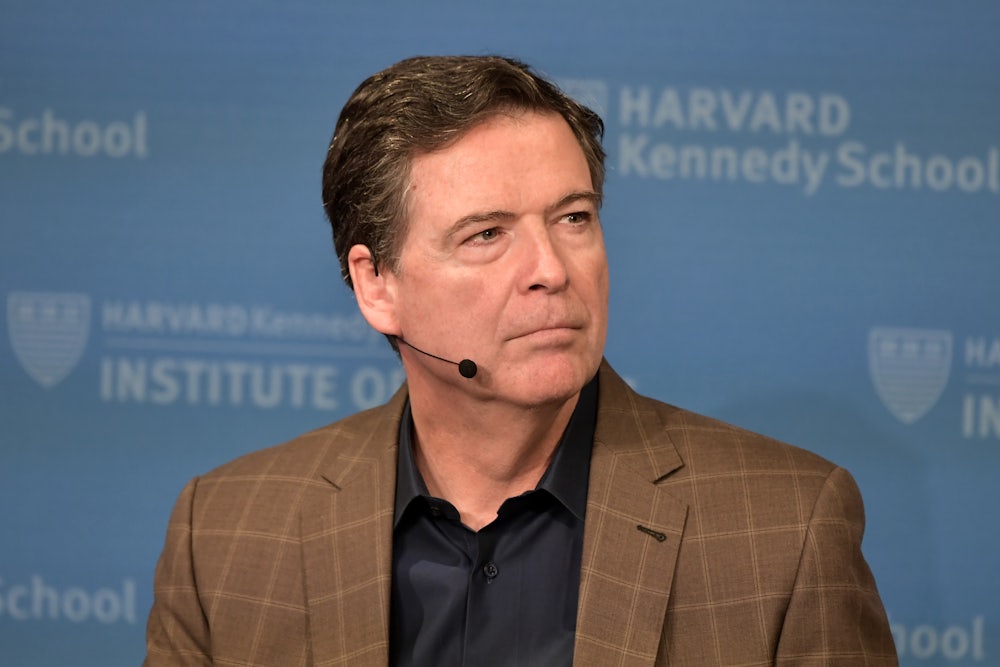

President Trump’s lawlessness has just taken another turn for the worse. It’s being widely reported that Trump’s Justice Department is likely to indict former FBI Director James Comey, someone the president has hated for years. Yet this comes after career prosecutors reportedly informed DOJ political appointees that they have not been able to find evidence that would sustain a conviction. This comes as Trump unleashed a really corrupt tirade about James Comey and a second strange rant about right-wing political violence that seemed to again absolve his own side. And we also just learned that DOJ is looking for ways to launch a criminal investigation of billionaire Democratic donor George Soros. How should Democrats and liberals in the media talk about this level of lawlessness? Is our current language adequate? Talking Points Memo editor-at-large David Kurtz has a great new piece arguing that it is not—that Trump’s unparalleled destruction of the rule of law requires a whole new language to adequately describe what’s really happening here. So we’re talking to David about all this. Good to have you on, man.

David Kurtz: Good to be with you, Greg.

Sargent: So the latest we have on James Comey is that DOJ is racing to find a way to indict him by next week for lying to Congress in connection with the Russia investigation, I guess. By the time listeners hear this, there may even be an indictment. Yet this comes even as The New York Times reports that career prosecutors investigated Comey and found insufficient evidence to obtain a conviction. David, can you bring us up to date on all this?

Kurtz: Sure. So last week, Trump fired or forced the removal of the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, who Trump had nominated for the permanent position. So this is one of his people, but in fairness, a career person. And he’s replaced him with Lindsey Halligan, who was one of his personal attorneys down in Florida and has been a White House aide. And it’s clear that the reason that the last guy was removed was that he didn’t pursue indictments against either James Comey or against Letitia James, the New York attorney general, who has a separate bogus mortgage fraud claim being alleged against her. So it’s 100 percent clear to everyone that Halligan’s got marching orders to go in there and secure these indictments— whether there’s evidence or not, whether they amount to a crime or not, Trump wants this done and he’s insisted it be done. It’s clear what is in the works and it’s clear that it’s in bad faith. It’s clear that it’s part of his retribution campaign that he has promised and threatened for years now. And so I think the presumption can be that these are bogus prosecutions, that they’re not valid, that they’re done in bad faith and they’re part of his corrupting of the justice system.

Sargent: Well, Trump addressed this directly on Thursday. As you say, it’s been widely reported that Trump is directly pressuring DOJ for these prosecutions. Here’s what Trump said when asked by a reporter about the situation.

President Donald Trump (voiceover): Well, I can’t tell you what’s going to happen because I don’t know. We have very professional people headed up by the attorney general and Todd Blanche and Lindsey Halligan, who’s very smart, good lawyer, very good lawyer. They’re gonna make a determination. I’m not making that deter–, I think I’d be allowed to get involved if I want but I don’t really choose to do so. I can only say that Comey’s a bad person. He’s a sick person. I think he’s a sick guy actually. He did terrible things at the FBI and.... But I don’t know. I have no idea what’s gonna happen.

Sargent: So there it seems like Trump is angling for some sort of plausible deniability. He wants to avoid the obvious charge that Comey is the victim of selective prosecution. But funnily enough, Trump couldn’t even help but again, express his desire to see Comey prosecuted even during that tirade. Can Comey point to this selectiveness? What’s the significance of it?

Kurtz: Yeah, I mean, a few things there. You’re exactly right. He puts up a tissue-thin veil between [him] and the Justice Department that anyone can see through. So it’s a nod and a wink at best. Second, I think what he’s getting at, which is good for us all to remember, is that with the immunity decision, the Supreme Court has given him such wide latitude that he can corrupt the Justice Department with impunity and there’s no obvious recourse other than impeachment, which we know is not going to happen with a Republican-controlled Congress. So, like, structurally, he’s not wrong with how things have played out over the last year—even though ethically, legally, politically, and in all the ways that we value, he’s clearly wrong.

In terms of what the implications are for the Comey prosecution, I think judges see what’s happening. I think these kind of demonstrations make it clear that they’re going to have to put prosecutors to the test on all of these in a way they haven’t had to before, or wouldn’t even have had to think about putting them to the test before.

I can’t really hazard a guess as to how these are going to play out. But I will say it will be case-by-case. Each case is different. The facts are going to depend on each case. But I don’t see and I don’t think your listeners should see these as, like, somehow a get out of jail free card. I think there’s a very real possibility. And I know maybe not in Comey’s case and I think some of the other ones are pretty weak.

But I think there’s a real possibility that some of these are going to lead to convictions and they’re going to have been, you know, predicated in bad faith, investigated in bad faith. And they may still get them over the finish line just because of the amount of power and discretion that prosecutors have. And it’s historically used, for better or worse, with a fair degree of wisdom and professionalism and oversight compared to what we’re seeing now.

Sargent: Well, what does the law say on this topic? Putting aside the fact that the Supreme Court essentially gave Trump a blank check, how far [do] the president’s powers go? How far do DOJ’s powers go? Can Trump order a prosecution in the full knowledge that the evidence doesn’t support it? Are there any constraints?

Kurtz: So I would say that there are fewer constraints than most people would believe or would hope. I would also say that there’s a rapidly evolving legal environment and some of these questions don’t have concrete answers yet. Structurally, from a constitutional standpoint, I don’t think that there is—at least in the eyes of the Roberts court—anything that would prevent Trump from directly ordering his attorney general to seek an indictment of someone.

Historically, we’ve seen that as a bright line not to cross. And Watergate was the great example of what happens when you give the White House too much direct control over the Justice Department. But the Chinese walls that were erected, the traditions, the norms, all the things that we’ve grown tired of talking about over the last decade that Trump has trampled, were there by tradition, by an understanding that was good judgment and wisdom, but not by any legal constraint or any legal requirement. And so to some extent, there is no sort of guardrail there.

Now, that being said, we’ve seen grand juries stepping up and deciding that some cases that they brought, particularly in D.C. with the surge and police here, with the riots in L.A., grand juries have stepped up, like, “These are not appropriate charges. We’re not going to indict these,” and that’s forced DOJ to file misdemeanors versus felonies in some cases. You know, judges have expressed a great deal of skepticism in some of these cases about how DOJ has been handling.

So I don’t want to suggest there are no guardrails, but I think they’re not as firm and they’re not as concrete as people might imagine them to be. And that’s what creates so much risk around having someone like Trump who has no regard for any of them. And even if we had more formal ones, he’s knocked many of those down already. Immunity is the prime example.

Sargent: Yeah. Well, it looks to me like institutional actors are going to be the ones that have to step up. I want to go a bit broader here. Listen to this from Trump talking about political violence.

President Donald Trump (voiceover): But the radical left is causing this problem, not the right, the radical left. And it’s going to get worse. And ultimately, it’s going to go back on them. I mean, bad things happen when they play these games. And I’ll give you a little clue, the right is a lot tougher than the left. But the right’s not doing this. They’re not doing it. And they better not get them energized. Because it won’t be good for the left. And I don’t want to see that happen either. I’m the president of all the people.

Sargent: It seems like Trump’s project is to create a two-tiered legal system in which he and his supporters are above the law entirely, and all his enemies, whoever gets designated that way at any time by Trump, are not just subject to the law, but subject to the corrupt application of it. In this kind of schema, the law is entirely instrumental, isn’t it? This goes to your piece, which was really, really good. I strongly recommend people read it. How do we report on this level of corruption of the rule of law? How do we talk about it?

Kurtz: Yeah, I think it really is key to see these prosecutions as the corrupt act, and not cover them like we historically would have covered a criminal prosecution, where the corruption or the bad act is the underlying criminality being alleged, nd the question is whether that person is guilty of it or not. In these cases, even if you have a case where maybe it’s both, right? This is a foe that Trump wanted to target and also they committed bad acts.

I think we need to be really mindful that many of these cases wouldn’t have been brought in the first place, that we don’t really have any presumption anymore that what we’re hearing from DOJ, from law enforcement can be trusted, is reliable. And I think there was some presumption of that before.

I think there was a—for years, a legit criticism of journalists that they were too close to police, too close to prosecutors. And what they were getting was too much the government side of things. But, especially now, that that is abundantly clear that we can’t trust, we can’t rely [on them].

And so if we use the same—this is what I argued in the piece—if we use the same journalistic tools, if we use the same coverage that we have for years in covering these things, all we’re going to do is reinforce that James Comey, or whoever the target is, is a bad actor, a villain. When in fact, what we really should be concerned about is the public corruption involved in abusing his office and abusing the office of the attorney general to bring cases that shouldn’t have been brought in the first place.

That’s a line we’ve never crossed before, but now have crossed. I mean, we have the John Bolton investigation already underway. We have the ones with Letitia James and Comey, and there’s no reason to think there won’t be others and maybe already are others. You’ve got Ed Martin, the weaponization czar at DOJ, running around, wanting to investigate everyone to sort of flatter and win favor with the White House. So it’s underway, is the point, and we need to adjust how we cover it to reflect what the new reality is.

Sargent: Well, just applying your framework for a second to that audio we just heard in which Trump essentially absolved his own side of political violence. The story there should be that Donald Trump is explicitly declaring that his own supporters will be above the law as long as he controls the legal apparatus, correct?

Kurtz: Yeah, I heard that as a kind of a mix of we’re tougher than they are, and so if it’s going to be a brawl in the streets, we know who’s going to win. But also, as you say, an element of absolving, as he did with the January 6 rioters, for example, as he did with the, the seditious conspirators, right? He’s already gone down this road. This isn’t new. We’ve seen him apply the law this way already against—or in favor of his side when they’ve committed political violence. I mean, I think that’s the defining—really the defining thing of the second Trump term, that he did that immediately upon taking office earlier this year.

Sargent: Yeah, and I think there’s actually a through line between the two elements you identified in that rant from Trump. And the through line is basically that he’s creating a system, a world in which there isn’t really such a thing as legitimate guilt and innocence, right? It’s just power all the way down. Everything is just a war, and that’s it. Whoever wins wins, and whoever loses loses. That’s what I think is happening here really.

Kurtz: I think you’re right. I mean I think in this worldview of his, the Justice Department is a tool, prosecutions are a tool, to be used to punish, to favor. I mean it is transactional.

Sargent: Intimidate as well.

Kurtz: Yes. Yes, and I think we should be clear that it’s it’s not just intended to punish James Comey or Letitia James, it is intended to chill the discourse, it is intended to have people retreat from the public square, it is intended to suppress dissent, and has a number of other sort of civic ills ... associated with it beyond just the utter injustice to the individual people who have been targeted.

Sargent: Really want to pick up on what you just said there, because it’s absolutely essential. I have spoken to members of civil society, liberal advocacy groups and so forth. Look, let’s just face facts. All this stuff absolutely will chill political activity on the liberal side. Lots and lots of actors in the system are going to have to ask themselves whether they want to risk coming under the kind of crosshairs of prosecution from Donald Trump and Ed Martin and the whole weaponization crew. That is just a fact of life right now in American politics that we just can’t deny.

Kurtz: It is. And it’s something that I hear a lot of, people need to stand up individually and as institutions. And I agree, they do. I think it’s easy for us to overlook when we are not the ones on the front lines necessarily, at least not yet, the difficulty, the personal cost, the personal price of standing up, the real risk. It could be reputational, it could be financial. It could be your liberty. All of those things are in play and we need to find ways, I think, to imagine a way in which we can support that, we can create a culture that’s supportive of that. But also real ways of supporting people who are taking it on the chin, who are on the front lines of dealing with some of this, because it’s not going to go away.

And there is, I think, a sort of a cascading effect. People get worn down. And over time, more and more people retreat and it becomes harder and harder to sustain a civil discourse, a civil engagement when people just don’t want to be involved at all for legit reasons. For personal legit reasons.

Sargent: Right. And I think that’s why things like Jimmy Kimmel kind of prevailing really matter. It lets people throughout the system know that there’s support out there for people who are willing to buck the trend into lawlessness. I want to play one more audio, this one of Congressman Eric Swalwell.

Congressman Eric Swalwell: What I would just say to any prosecutor at the Department of Justice is it’s not going away. As a member of the Judiciary Committee, I promise you when Democrats are in the majority, we are going to look at all of this. And there will be accountability. And bar licenses will be at stake in your local jurisdiction if you are corruptly indicting people where you cannot prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt.

Sargent: David, it seems to me Democrats should do more of this. Just say straight out that anyone who carries out corrupt or illegal orders for Trump will face accountability later. Tell us, what does the law say on this? Can prosecutors who carry out corrupt prosecutions be subject to legal accountability in any way? What are the tools available here?

Kurtz: So there’s a few, but I’m concerned that I will overstate their effectiveness just because I think people want so badly to believe that there can be consequences for this—that we’re hungry for it, right? So yes, I think if you end up with a new administration with a new DOJ that comes in and cleans house, that you have a number of professional things that can be done within DOJ, you have state bar associations or bar licensure processes, there’s discipline processes, there’s a whole range of those kinds of things. But look, I think we’ve already seen in the last 10 years that they’re slow, they’re not quickly responsive to the urgency of the moment, and that it doesn’t have the sort of structural impact that I think we’re looking for. So it’s not that there are no consequences to be had, but I think that they are harder to come by. And it would take more than just Democrats winning the House. It would take more than just winning Congress. I think you would need to win the White House for there to be a chance that some of this could ultimately be looked at as criminal or corrupt in its own right.

But I was interested [in] one thing he said. I think he’s speaking to two audiences, right? I think we need to remember that within justice, there are still career people who are probably struggling with how to reconcile trying to do good work with the bad situation they’re in. And then you have the politicals, who clearly are running sort of roughshod over any justice department traditions, any of the normal processes and procedures. And so I think we need to keep in mind that there [are] two elements. And one of the things I’m worried about is that those folks who went there for good reasons and have good intentions and want to try to fight their way through are slowly going to be eroded and shut aside and ultimately retreat from this fight as well. And then we’re going to be left with even fewer guardrails within justice itself.

The kind of thing that you were talking about in the Comey case is career people being like, “We don’t have ... there’s just no evidence. We can’t bring this.” You need those kind of people around. And if those people leave, it’s a tough spot to be in. So I think Swalwell was talking more to the politicals than he was to your line prosecutors. But it’s helpful for them to hear that they’re going to have the support. It’s almost like, “Hang on. Help is coming.” I think realistically, help is still three, three-and-a-half years away at best. It’s a long haul.

Sargent: Well, just to be overly optimistic about this, let’s talk about what happens if there’s a Democratic House to close this all out. You could see a situation where a Democratic House could potentially get very creative in using the oversight process to just hound the absolute fucking shit out of the politicals who are corrupting the system while creating new avenues for career people internally to speak out, for whistleblowers to speak out. I think you could at least get some sort of political momentum going and some sort of countervailing pressure that could actually matter in some way. What do you think?

Kurtz: No, I mostly agree with that. And I don’t mean to suggest that it would make no difference if you had a Democratic House. I will just note that the level of oversight that Democrats provided in the first term was not as aggressive in any way, shape, or form as what you’re describing. And I think that there were—you know, they hopefully learned the lesson that subpoenas can be ignored, that a lot of these legal fights will drag on for years, and that you have to find a way to both use those tools, find other tools to use, and wrap it all in a public sort of presentation and public pressure campaign that, as you say, keeps the heat on so that the politicals feel, if not accountability, at least, you know, some heat.

And, and I think that whether they’ll do that, whether they’re geared to do that, whether—that I think what we’re seeing, Greg, and this is way big picture, is I think there’s lots of folks in politics who came up in a different time, in a different era, where the moment required different skills. And I think part of the adjustment that we’re going through politically right now is sort of re-staffing our politics with folks who can kind of confront the current moment as is required. And that takes time and maybe we’ve been slow off the mark in getting there, but I think it’s gonna take that for it to be as robust a response to the Trump Two presidency as is needed.

Sargent: Well, if there’s one thing that Trump 2.0 is really driving home, it’s that the old understanding of politics and the old understanding of tactical approaches to these situations has to be just chucked out the window. And a new understanding has to be brought into play. And I think you’re seeing the Democratic Party move that way with quotes like this from Eric Swalwell. It’s slow, but some of the younger people in the Democratic caucuses seem to get it. And look at Chris Murphy, for instance, the senator from Connecticut. He’s been incredibly vocal on this stuff. I do think that the Democratic Party is starting to see that a fundamentally new approach to political warfare is needed here. Do you think that’s plausible?

Kurtz: It’s plausible. You might be a little more optimistic about it than I am, but I’m not going to, I don’t want to rain on your parade about it. I think it’s challenging to the imagination. It’s challenging to our sense of what’s possible. It’s challenging to our self-identity, as what it means to be an American, as to what it means to live in a free society. I mean, there’s a lot of sand shifting under our feet. There’s a seismic change that’s occurred. And I think it’s understandable to an extent that it’s taking people time to figure out how best to respond to it. But I worry too that there was a bit of too much denial going into it and that’s partly why we’ve been slow to respond. So that’s why I think conversations like this and the story that I did today, I’m hoping that we can advance the ball on what we should be talking about and where we should be focused and not be held hostage to the old ways of doing things just because that’s how we used to do them.

Sargent: Democrats, get with it man. Get moving! David Kurtz—enormous pleasure to talk to you, man. Great stuff.

Kurtz: Thanks as always Greg. Good being with you.