On the fourth day I went to get a sense of the devastation. The street outside my building in lower Manhattan was still cordoned off on either end by police, and you needed an escort and proof of ID to get in or out. The young officer who stood guard on the corner said that two of his colleagues from the police station next door were missing. “A man and a woman,” he said. “We’re still hoping.”

I headed uptown to the Pierre Hotel, where I heard that the families from Cantor Fitzgerald—a bond-trading firm that had lost some 700 of its 1,000 New York employees in the World Trade Center attack—had set up an emergency center. It was in the Grand Ballroom on the second floor, where weddings and executive banquets were normally held, a place that seemed utterly incongruous for a crisis room. It was opened, along with the hotel, in 1930 and, according to the hotel’s brochures, had “received royalty, world leaders and celebrities.”

Outside the main door, the company had set up tables with information packets, including hot lines for “investigative tips,” “hospitals,” and “police.” There was a place to fill out missing person reports, and a few people gathered around it. The forms were eight pages thick and asked for anything that might identify the missing, including dental records (“partial plate,” “braces,” “no teeth”) and objects in the body (“pacemaker,” “bullets,” “steel plate”). On page four there was a checklist for build, race, and hair color, as well as items like wigs, toupees, and transplants. “Facial Hair Style: __Fu Manchu __Whiskers Under Lower Lip __Mutton Chops __Pencil Thin Upper Lip __N/Applicable.” There was also a checklist for dominant hand, fingernail type (“natural,” “artificial”), nail characteristics (“dirty,” “misshapen,” “decorated,” “tobacco stain”), complexion, dress, and, on the second to last page, a “DNA Donor Information” form.

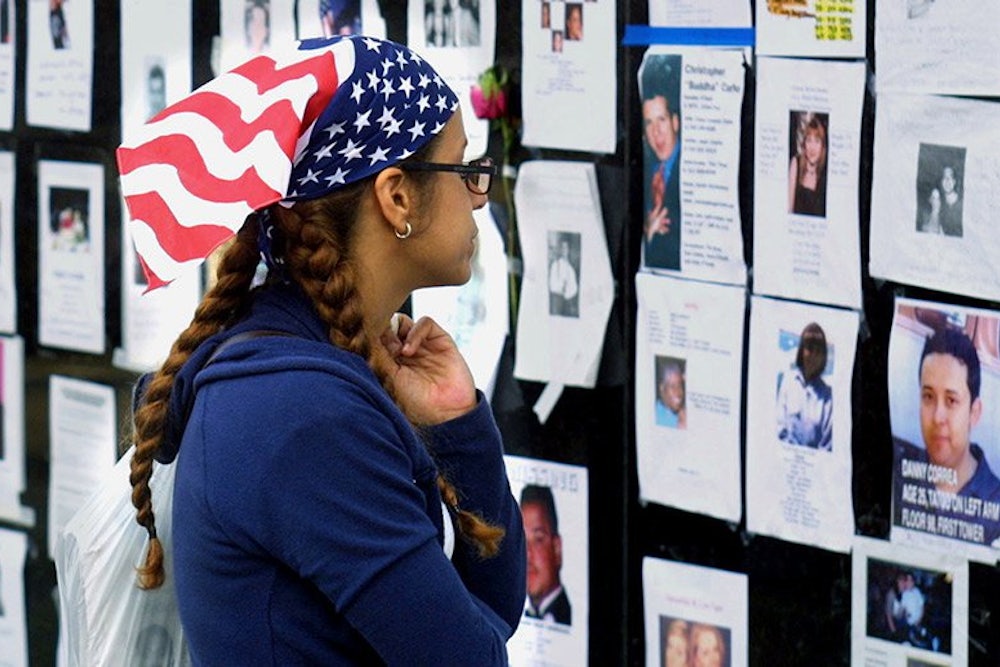

Inside the ballroom, tacked along the back walls, were sheaths of white paper, each with a picture and details of one of the missing. Some were written by hand, as if in haste, others typed in bold computer fonts. One said, “Adriane Scibetta 5 feet w/brown hair/brown eyes,” and had a photo of her with three little girls. Another said, “Francis (also goes by Frank or Fran) 28 years old/5’10”-170s lbs. Light brown hair cut very short. Green eyes ... two tattoos: a Shamrock in Irish flag colors with the word ‘Mom’ written in the middle of his right upper arm. Also a tattoo of the Chinese symbol for Mother on his right arm.” Underneath was a picture of him, his sleeve rolled up, so that you could see the word mom etched on his right bicep. Next to him was a picture of Amy O’Doherty. It had been mimeographed and her face was faded. Underneath it listed three “distinguishing characteristics”:

Freckles

Large Chest

Diamond stud earring

I walked from one wall to the next, staring at the faces, reading the captions above them: “Have you seen Mr. Hashmukhrai Parmar?” ... “Have you seen these two cousins?”

A woman with two boys was putting up a picture, this one mounted on construction paper so it would stand out. “Put it up over here,” the woman said to one of the boys. “There’s more space.”

As you stepped deeper into the room there were dozens of round tables draped with white cloths and surrounded with gold-painted chairs. Four to eight people were sitting around each, lit by rococo chandeliers. Off to the side was a buffet table with Cokes and Perrier in buckets of ice, and ham and cheese sandwiches on French bread, neatly sliced, with mustard and lettuce. Waiters moved through the room holding silver platters, as if it were just another company Christmas party. But as I looked more closely I noticed a number on each of the tables, beginning with 101 and going up to 106, and I realized that these were the floor numbers where the missing had—that the room had been arranged according to where the victims had, in all likelihood, last been seen. There was a steady hum as people leaned over the tables, exchanging information and working their cell phones.

At one point, as I was standing there, a woman ran up to me and said excitedly, “Are you Martin?”

“No,” I said, not sure if Martin was one of the missing or someone who potentially had information. “I’m sorry.”

When I said that I was a reporter a man nearby asked if I had been to ground zero recently. His brother, he said, was missing. “First our tactic was to find anyone who saw him,” he explained. “Now our tactic is to find anyone who made it out of these top floors.”

He drew a diagram on a piece of paper, showing me where all the stairwells and exit routes were and how the forces had brought down the building. “My brother is strong,” he said. “He may have made it into the basement.”

Eventually I sat down at one of the tables marked 101. An elderly couple, Carlton and Coletta Valvo, had just arrived from California. Because the airports were originally closed, they had driven to Vancouver and flown to Toronto and then rented a car and rode all night to New York. The father had graying hair and thick black glasses that made his eyes look enormous. He said his son, Carlton Jr., was 38 years old and a vice president. He had just gone to work for Cantor Fitzgerald and had a wife and a seven-year-old daughter. “He spoke to my other son on his cell phone and said, ‘I don’t know if we can survive. There’s smoke. I got to go.’”

“You could hear screaming,” said the mother, Coletta. “Then the phone went dead.”

“I’m a doctor,” the father continued. “I have a sense of reality, but—”

“We still have hope,” his wife interjected. “There are miracles.”

Later, while I was talking to someone else, Dr. Valvo tapped my shoulder and said he wanted to show me something. He took my arm and led me to the back, where hundreds of photos were pasted. “There,” he said, pointing. “By the American flag.”

Amid the many photos, I saw a young face staring out with the same Coke-bottle glasses as his father. “We gave him that Hawaiian shirt at his brother’s wedding party,” he said.

When we sat back down the others were talking about ways their family members might have escaped. One man who had been at the table earlier, we were informed, had said that his brother was a Navy Seal and could spend at least six days in the rubble without food or water. Mrs. Valvo said that there was a gap between when her son had called and when the building collapsed, leaving the family some hope that he had survived.

But Dr. Valvo didn’t seem so sure, and when the others weren’t listening, he showed me a copy of a leaflet from the American Red Cross he had gotten for his daughter-in-law and seven-year-old grandchild. “I thought it might help.” It said, “after the disaster ... The following common, normal reactions may be experienced: Disorientation ... difficulty concentrating ... trouble sleeping ... headaches ... skin disorders ... sadness/apathy ... guilt/self-blame ... moodiness/irritability/emotional outbursts ... increased use of caffeine, alcohol or drugs ... ‘flashbacks’ ... nausea ... changes in sexual desire or functioning.”

On the back of the leaflet it had a special section on how to help the young who had lost family members. “If they are upset about what has happened, children may experience the same reactions as adults, plus the following: Bedwetting, thumb sucking or other earlier-age behaviors...”

There was a podium up front and a man rose to address the crowd. He said that he worked for Cantor Fitzgerald and asked everyone to fill out missing person reports. “If you haven’t done that yet, please immediately go to the reception area... Are there any questions?”

A slight woman got up and asked if rescue workers had found anyone from the company’s floors yet. He said there had been “rumors” but nobody so far. (A woman later told me that she had seen a man crying yesterday into his cell phone after hearing that his relative was alive—but that the man was now back in the room with everyone else. “I guess it wasn’t true,” she said.)

Not long after, a gentleman stood from table 105. “What were the evacuation procedures for our floor?” The man at the podium said he wasn’t sure, when a woman leaped to her feet and said, “I don’t understand what we’re all doing here. There are a thousand employees missing and we are the only company that can’t find anybody—not a single person—and we’re sitting around eating sandwiches. Why aren’t we doing something to get our people out of the basement who are stuck ... under 70 feet of concrete?”

The man at the podium tried to speak but the woman cut him off: “You’re a million-dollar company. Why aren’t you bringing in engineers from around the country?”

“I understand your frustration. But we are not an engineering company. We are a financial service company.”

A grief counselor who had sat down beside me told me that most people in the room still didn’t want to talk to him—that most believed, even after four days, that they would find their loved ones. “No one is prepared for tragedy,” he said later, “but these are people who are not normally struck by it.”

In the center of the room, several families had gathered around two televisions, watching the latest news. I noticed one girl who had been staring at it for hours. She had olive skin and looked like she was in high school. She told me her 29-year-old brother was missing. “My mother keeps saying, ‘Thank God I have you,’” she told me. “I think my mother is still in denial and my father knows but he won’t speak. I think my mother and I are just blocking it out and my father is thinking about what my brother was going through, but I can’t think about that because if I think about that....” On the television you could see the second tower collapsing. “I’m never going to be the same,” she said. “I was just thinking of going into sales because I’m such a people person... But I’m not going to be that person anymore. I just want to sit behind a desk and not speak to anyone.”

On the television you could hear a tape recording from Kenneth Van Auken, a Cantor Fitzgerald employee who called his wife and said on their answering machine: “I love you. I’m in the World Trade Center. And the building was hit by something. I don’t know if I’m going to get out. But I love you very much. I hope I’ll see you later. Bye.”

People seemed eager to talk to a reporter. They came up to me—in contrast with the grief counselors—and handed me posters, stuffing them in my hands and pockets. I filled notebook after notebook with their stories. At table 106, a 34-year-old mother named Annette Vukosa leaned over and told me she had two children, a two-year-old and a seven-year-old. “The oldest doesn’t want to hear his father might not come home,” she said. “I told him, ‘We’re looking for your dad, but no matter what happens I really love you and I will take care of you.’ But he said, ‘My daddy’s here. He’s going to take care of me too.’” She paused. “When we used to go to Manhattan, his father would tell him, ‘You see the tallest building? That’s where I work.’”

I sat with her, looking at pictures of her family, until the room fell totally silent. Howard W. Lutnick, the head of the company, had arrived to give the latest updates on the search. He wore a black suit and his hair was slicked back over the top the way brokers often seem to prefer it. I had read in the papers that he was a fierce executive, someone who overwhelmed his rivals in the financial world. But as he surveyed the ballroom he seemed almost diminutive. He had survived Tuesday only because he had taken his son to school and had arrived at the Twin Towers just before they collapsed, as people were streaming out. “I’ll do what I always do,” he said now. “I’ll tell you everything that I know. But I don’t have all the answers and some of the things I say could be wrong and if it doesn’t work out that way, I have just one rule: You can’t be mad at me. Because I’ve had two people angry at me, as if somehow I did something.” He paused, wiping his eyes. “So I just ask you, if someone is mad or angry or they think you did something wrong just try to remember ... no one’s better and no one’s worse and no one’s right and no one’s wrong. We’re all suffering.” He inhaled deeply. “So I’ll tell you what I know. We’ve now confirmed that two of our employees’ bodies have been found. Two people. They were on our floors. They did it with dental records. So for those of you who want me to, I’ll say it as plain I can: They are no longer looking for survivors. They are now in the process of trying to find our families. That’s what they’re doing.”

The room filled with cries. I could see Dr. Valvo holding his wife and the girl who had lost her brother slumped over and Annette reaching for her sister. A moment later a young man rose in the center of the room and started to shout, “Don’t you take our hope! Don’t you take our hope!”

Lutnick said he wasn’t trying to. But the man continued: “How can you tell us we won’t find our families when they are still looking for them?”

“I’ll tell you why,” Lutnick said. “Because my brother Gary Lutnick called my sister that morning and said, I’m stuck on the 103rd floor. I am trapped and there is no way out.’”

He started to weep. “We are all on the same side,” he said. “We all want our loved ones to be alive. We need them to be alive. They have to be alive. But you know what, they may not be. If you don’t want that to be today, then I’m not telling you that it’s today.”

After a while Lutnick led everyone outside for a candlelight vigil and I broke off and headed home. As I came down Lexington Avenue I began to notice more and more white posters. They covered the railings, lampposts, and windows. It was getting dark but I could see the captions in the fading light: Chris M. Kirby ... a carpenter ... 152 lbs ... blue eyes ... William Kelly Jr. ... 6 feet ... 175 lbs ... Timex Ironman watch on left wrist ... Tonyell McDay ... African American ... approximately 5’4” ... ruby ring on left pinky finger ... Colleen Supinski ... large blue eyes ... long thick eye lashes ... tiny wrists and fingers ...

When I reached 27th Street the posters were everywhere, spilling out of newspaper boxes and telephone booths. I recognized some of the faces from the Pierre, but there were now hundreds more. I realized I had reached the Armory, where not just the people from Cantor Fitzgerald came, but all the victims’ families filing their missing person reports. Crowds of people were walking around, holding lit candles, and handing out posters. “Have you seen this person?” a man said, showing me a picture of a young woman. He held up a candle so I could see it better. I shook my head. But when he saw my reporter’s pads, he started telling me about his daughter. I didn’t have any more space in the notebooks, but I turned over a poster and, under the light of his candle, began to write.