Originally published on December 4th, 1944.

One could say that Henry Miller is a preacher who frequently hits on a perfect pitch of narration, or that he is an extremely good story-teller who occasionally writes a lot of nonsense about Lawrence, the astrological destinies of the world and the various apocalypses, including the apocalypse of Henry Miller himself. The fact is that one cannot get away from Miller so easily. I mean by simply admitting on one hand that he is a good writer while ignoring the substance of his writing, and by overlooking, on the other hand, the perfection of the compactness of his best pieces because his generalizations about himself and the world are so often, and so literally, extravagant: flights into universes for which he has no essential concern.

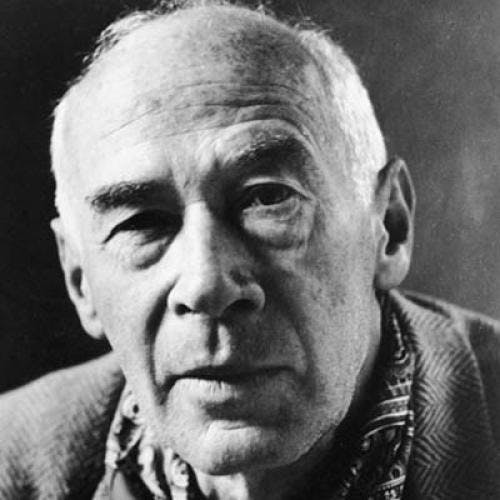

Essentially, he is just Henry Miller, from Brookyln, who left America in 1930 because he couldn’t stand it any longer, lived in Paris for nine years, writing there the first book of his new life” as an act of desperation,” and was forced to return to America from Greece in 1940 because of the war. In a revealing biographical note added to “The Cosmological Eye” he reveals how as a young man he worked “at anything and everything and started writing, although “almost afraid to think” of becoming a writer. His readers know of his astonishing way of handling the job of a personnel director for Western Union, and the things he learned there. And it is not unimportant to keep in mind, in connection with Miller’s indictment of the ways of modern society, what he himself has taken care to point out: “the most important encounter in my life,” he writers in the biographical note, “was with Emma Goldman in San Diego, California. She opened up the whole world of European culture for me and game new impetus to my life, as well as direction. I was violently interested in the IWW movement at the time it was in swing, and remember with great reverence and affection such people as Jim Larkin, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Giovannitti and Carlo Tresca.” But the real autobiography of Henry Miller has to be sought in his books.

It is easy to point out, in this last collection (“Sunday After the War”, by Henry Miller) of pieces from Miller’s work, the story, “Return to Brooklyn,” as a masterpiece. It is the plain, admirably firm and even tale of the return of Henry Miller (not of any imaginary character, and of the artificial “I” which helps to dodge so many questions and facts, just Henry Miller, the real character that Henry Miller has been describing for ten years) to his mother, father and sister, to his home in Brooklyn, after ten years of exile. Céline has written some forceful pages on the family, but Céline is jittery and mean; he hated the family because it is the thing most hostile to his moods. His revolt has no dignity. In Miller, there is neither hate nor revolt, rather a most controlled pity a very human modesty. To him, the family is simply the desolate core of the inertia of which our society is dying.

The description is hopeless and pitiless, yet with no overtones of despair or disgust. Even in the details about the miserable disease of which the father is dying, there is no crudity, but rather the compassionate detachment of the monk (and a peculiar kind of monk Miller certainly is) who cannot think of the sick he is tending otherwise than as samples of human misery. The horror is in the existent of being drained of all life, neither by fate nor time, but by the blind machine which has tkane the place of human society. One has only to think of what Céline would have done with the same material, or for that matter, of the truculence in which Miller used to indulge in his early work, to realize how near he has come to a real harmony.

To stop here would be merely to praise Miller from a distance, and avoid his personality, a philistine attitude and one which would not do justice to the writer. The originality and forcefulness of “Return to Brooklyn” do not consist in the realistic descriptions of a milieu, but in the honest account of a relationship. The main character of the story is neither Henry Miller nor his family, but their relationship, their presence together as individuals on equal terms, and the questions that this co-presence raises. In other words, the real subject of the story, what creates its suspense and dramatic quality, is a moral struggle, the struggle of Henry Miller, the character, against the torpor of sentimental ties, against his own frailty and helplessness, and more especially against the smoldering fire of rage and disgust, to attain whatever clarity and justice it is possible for him to attain toward that environment and those human beings. From this struggle, Henry Miller comes out the winner, not perhaps in the sense that he thinks as a man who discovered essential truths, but as one who has succeeded in mastering his inner chaos and in not allowing the external clutter to overcome him.

It is in this sense, I think, that Miller was right when he wrote of himself: “I am at bottom a metaphysical writer, and my use of drama and incident is only a device to posit something more profound.” A device, I would add, to elucidate as far as he can what is actually going on around him from the point of view of the unattached individual with no special interests to defend or hide, except the personal whims and twists of which is a victim like anybody else.

I don’t know any other writer who has succeeded in completely humanizing the writer as a character, stripping him of any special prestige, making of him a true Everyman who wins his laurels, if any, only in actual competition with other individuals for the possession of human qualities and for the enjoyment of whatever there is to be enjoyed in life. The exhilarating quality of Miller’s best things come precisely from the fact that he has succeeded in making of writing a natural way of existing, and also in making of the reader a companion in the material and moral odyssey, the dejection, the hunger, the shame, and the very real pitfalls which have to be experiences by an individual in order to have that kind of existence. Before preaching about deliverance from what he calls the dumb sleep of the present world, and one would add, more than preaching about deliverance, miller has shown the actual process of deliverance of a perfectly ordinary human being from the gutter of Broadway and the officer of Western Union to the streets of Paris, from the blind rage and despair of the cornered individual to the conquest of that tense detachment which is the best quality of Henry Miller, the character and story-teller. Writing, for him, is the actual process of purification from confusion and insincerity, by no means and end in itself, as he explains very clearly in some pages of this last book:

The little phrase--why don’t you try to write?--involved me, as it had from the very beginning, in a hopeless bog of confusion. I wanted to enchant but not to enslave; I wanted a greater, richer life, but not at the expense of others…I had no respect for writing per se…By a chain of circumstances having nothing to do with reason or intelligence I had become like the others—a drudge…I gave nothing to the world in fulfilling the function of breadwinner; the world would only begin to get something of value from me the moment I stopped being a serious member of society and become--myself…What I secretly longed for was to disentangle myself of all those lives which had woven themselves into the pattern of my own life…To shake myself free of these accumulating experiences which were mine only by force of inertia required a violent effort.

It is the tenacity and consistency of such an effort that the seriousness and uniqueness of Miller’s personality lie, no matter how often Miller himself falls victim to what he calls the “vice” of uncontrolled imagination, metaphysical, psychoanalytical or simply erratic, and also no matter how often he boasts of having attained perfection.

I must confess that when I first read “Tropic of Cancer,” as much as I admired his talent as a narrator, and realized that here was somebody arriving from the “end of the night” and who had, as such, the right to be respected, I was mystified by the atmosphere of elusive egotism which accompanies him, and would have agreed with what George Orwell was later going to write: that Miller was seeking a refuge from the murderous nonsense of the present world “inside the whale,” in an attitude of total indifference and frantic self-preservation. Still, I was not convinced. I felt there was in Miller’s work an additional quality which I was unable to grasp. It was under the impact of the insistence and consistency of his successive works that I realized there was more than good story-telling in him. His tales of desperate wanderings through Paris, of Noew York tailor shops, of true trivialities and obscenities, of crazy bohemians and nasty tricks, not only gave one the immediate feeling of the casualness, the lack of logic, the utter imperviousness, the humor of real life; they also compelled one to enjoy it with a sense of liberation, the liberation from any special sentiment, from any moral or intellectual prejudice. And most important of all, it was a keen pleasure to know what such a man existed in such a world as the world of today.

As for Miller’s aloofness, I would agree that he prefers to play with astrological symbols rather than with political ideas, and to praise Bahai rather than Marx. I would not deny that he often shows more than a little affection in this sense. But on the other hand, it is so clear that everything he conceives or feels is conceived and felt against the world of today, that I would hesitate to accuse him of the very opposite, too emotional a concern with some of the obvious aspects of the present evils. In his beautiful book on Greece, very discover, every pleasure, and laugh, and moment of pure oblivion is felt against the background of impending catastrophe. Greece would not be so beautiful and pacifying were not the world side of Greece so ugly and inhuman. Miller’s egotism, in so far as it is insistence on self-possession, seems to me perfectly valuable, and it certainly is one of the inescapable themes of modern literature. As for his vaunted bliss, it is not without meaning if considered against the background of pointless sadness which one finds everywhere today, among all kinds of people, and which Miller calls “Hamletism.”

In any case, I think that Henry Miller means it he writes:

I am here on earth to work out my private destiny. My destiny is linked with that of every other living creature…I refuse to jeopardize my destiny by regarding life within the narrow rules which are not laid down to circumscribe it. I dissent from the current view of things as regards life within the narrow rules which are not laid down to circumscribe it. I dissent from the current view of things as regards murder, as regards religion, as regards society, as regards out well-being. I will try to live my life in accordance with the vision I have of thing eternal.

Nicola Chiaromonte