There in the affairs of men ... when it is time to go. Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier seems to have missed the boat. A year ago, when things were still pretty quiet in Haiti, he could have gone off with his wife, children, entourage, designer clothing, Gucci bags, Vuitton luggage, and les musts de Cartier and retired to one of his Swiss or French properties to spend the proceeds of years of prudent squirreling against a powerless winter. Any excuse might have done.

But now it is probably too late, France doesn't want him. An embarrassed Francois Mitterrand, good Socialist that he is, feels that the sacred right of French asylum, always liberally accorded to such freedom-loving figures as Karl Marx (shortly withdrawn), sundry brigadisti rossi, and Khomeini was never intended to serve as cover for a man with so much blood on his record if not his conscience. Mitterrand’s masterpiece of understatement: "I don't know whether this person is really the best symbol of human rights in the world."

But if France doesn't like him, who will? The French thought they had made a deal: a rest stop and then away--back to American, if no one would take him. That was not our sense of the matter. We were concerned, we said, to make possible a peaceful transition to a better regime, not to serve as the haven for a royalist emigration. Since the Duvaliers are francophone, we feel, they would prefer France to the United States (and maybe anything to Liberia). Having taken in tens of thousands of Haitian refugees, we could not assure the Duvliers' security: too many angry people around. Besides, it is far more important to us than to France to maintain a good image in the Caribbean.

Meanwhile there is Haiti--a crowded piece of badly deforested and eroded land with the lowest income per head in the Western hemisphere. We hear talk of a new era: the institution of popular government; a resumption of foreign investment; a restoration of infrastructure; employment-creating enterprises--onward and upward. The program and goals are standard and unexceptionable. Getting there is the problem. After all, this is not Haiti's first chance. By 20th-century measures, it is an old country. Like the United States, Haiti won its freedom by driving out a European power in what Robert Palmer has called the age of democratic revolution. Haiti was known then as Saint-Domingue and was France's richest colonial possession. Its wealth came from sugar and coffee, above all from sugar, cultivated on large and middling plantations by slave labor. These blacks made up more than 90 percent of the population. Saint-Domingue was in effect a piece of Africa transported to the New World.

The rest of the population was about evenly divided between mulatto freemen (the "yellows") and the whites. Color was class. The yellows constituted an intermediate group between whites and blacks, serving as overseers, agents, shop clerks, craftsmen. The whites were planters, soldiers, merchants, technicians, doctors, clergy. Some of these had brought families from Europe. But Haiti was not a healthful place, and the wiser whites left wives and children at home in France. That was another reason for the creation of a Creole population.

The official religion--officially the only religion--was Roman Catholicism. But this moved only the whites, their households, and to a lesser extent the yellows. The blacks in the huts and fields, though touched by the white man's faith, retained a mix of African beliefs and practices that we still know as voodoo, with a strong component of sorcery. Whites and yellows spoke French. Blacks spoke a Creole mix of French and various west African tongues. Two worlds cohabited, both of them brutalized and terrorized by a relationship of power and exploitation. The great mass of sullen, smoldering slaves had to be kept in line by whip and fire. Their white masters, quick to punish, had nightmares of slave revolt. The hills were filled with marrons, rogue slaves gone over to plunder. The sugar estates and refineries were plagued by sabotage.

It was not the blacks, though, who were the most immediate enemies of the slave order. It was the yellows, nominally free but deprived of civic rights. They read the new literature of freedom put out by enlightened French opinion (the Society des Amis des Noirs was founded in 1788), and the outbreak of revolution in the mother country led them to demand immediate rather than gradual reform. In 1791 Paris granted them citizenship. The whites on the island, infuriated, sought to block enforcement. The yellows agitated, conspired, fomented resistance. And then in 1792 the blacks rose in revolt.

It took more than a decade to end the conflict. An initial period of anarchy and warlordism drove the French from the countryside into the cities, where they could shelter under the protection of military garrisons and naval guns. When they sought help from the home country, they found that the new revolutionary government was too busy fighting a coalition of European enemies to divert resources to the colony. Instead it sent out commissars, who in 1793 proclaimed freedom for the slaves. This no more ended the struggle than Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation would end the Civil War.

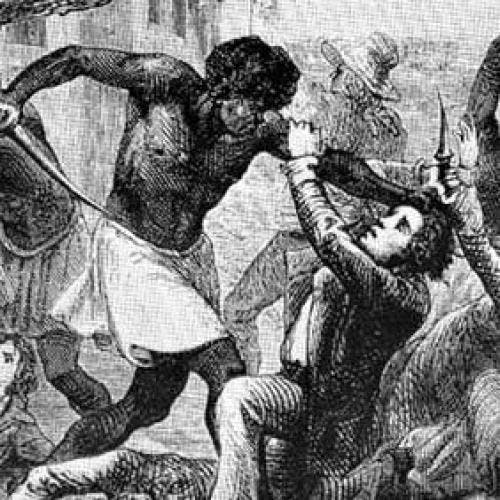

Nothing is so ferocious as a race war. It is war to the death. Black bands surged through the land, killing every white they could, from the oldest of invalids to suckling babes. White garrisons sallied forth and returned atrocity for atrocity. Prisoners were routinely massacred, which only discouraged surrender. There was even an anticipation of the Nazi gas chambers. The French fitted out a ship as a mass extermination machine: blacks were driven down into the hold and asphyxiated by noxious fumes. The name of the vessel: The Stifler. It was one of the quieter ways to go.

This first stage ended in 1796, when Pierre-Dominique Toussaint l'Ouverture, said to be the son of an African chief and destined for leadership, united the black armies and imposed a respite. The French, keen to save the form if not the substance, made him governor in the name of France, But then he declared himself governor-for-life, and Bonaparte in Paris was not ready to tolerate another Bonaparte in Haiti. In 1802 a French expeditionary force landed on the island, its mission to subdue the blacks. Binaparte had even bigger plans: Haiti, in combination with Louisiana, would be the making of a new French empire. But the invasion force was quickly defeated, as much by disease as by fierce resistance. The French, however, did succeed in trapping Toussaint by means of the most solemn promises: how could he not trust the bearers of liberté, égalité, fraternité? His captors took him to France in irons and placed him in an icy cell in a fortress in the Jura mountains. There this son of Africa, strong and valiant as he was, quickly shriveled and died of pneumonia. Napoleon gave up his American dream and sold Louisiana for two cents an acre.

Toussaint's successor, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, was filled with an immense, unappeasable bitterness. He drove out the rest of the French forces, and on January 1, 1804, proclaimed independence in terms that evoked the crimes of the past and promised more blood to come: "Citizens, look about you for your wives, husbands, brothers, sisters. Look for your children, your nursing babies. Where have they gone?" And then Dessalines personally led a massacre of every remaining French man, woman, and child in the country, excepting only a handful of doctors and clergy.

Haiti has cherished the memory of Toussaint, pupil of the Enlightenment, believer (and victim) of the hopes and illusions of a revolutionary era. But it also has remembered and honored Dessalines, savage in his hates, a man who turned his country in upon itself, the better to confront a hostile world. It is a mixed and bloody heritage, with the disappointed hopes of the one reinforcing and justifying the angry withdrawal of the other.

The effect of these barbarities is still being felt. The legacy of fire and blood was a population reduced almost by half and an economy in ruins. Fields and cities were laid waste; the sugar mills were a rusting mass of scrap iron and ashes. The houses were gone, the huts were empty. Nor were reconstruction and resumption possible, because the freed slaves wanted nothing to do with employment. No one wanted to work for another, because that was what slavery was all about. Instead, each wanted his own plot, to grow food for consumption and perhaps coffee for market.

But Dessalines needed sugar, because sugar was money and money was needed to pay for those forts and inland towns (away from the vulnerable coast) and a standing army consisting of up to ten percent of the population. So, in what was surely one of the most ironic betrayals in history, within two weeks of exhorting the Haitian people "to accept death in preference to the yoke," Dessalines proposed to open his ports to slave ships that would bring adult males for purchase by the Haitian government. And he offered a price for every Haitian refugee returned to the island. Neither measure helped, so Dessalines conducted a raid on the Spanish-speaking eastern part of the island. It was a raid to kill whites and capture blacks. It brought back some thousands of conscripts. Like the peasants assigned to forced labor in the fields, they were not called slaves, because slavery was forbidden by law. Whips were also prohibited, but adequate substitutes were found in vines (often with thorns) and sticks. The cocomacac, a heavy cane, could be very persuasive when it did not kill. Laborers, Dessalines pointed out, could be controlled "only by fear of punishment and even death," The Haitians had to kill Dessalines to get rid of him.

In the meantime, neither force nor fear could overcome a population schooled in resistance. Many of the plantations were now owned by mulattoes, who found themselves targeted as the new enemy. Like the French before them, they retreated into the cities, creating a color line between rural and urban. Sugar was finished. Even coffee exports dwindled, from 77 million pounds in 1789, at the peak of colonial prosperity, to 43 million in 1801, 32 million in 1832. As foreign earnings shrank, Haiti found it ever harder to make up domestic food shortages by imports. In the end, the government had to give up its hope of restoring cash crops and had to encourage subsistence farming. As the population increased, plots grew smaller, the earth poorer, people hungrier--a downward spiral of squalor and immiserization.

It was a poor basis for a democratic polity. This was a country with an elective presidential regime, but it quickly acquired the characteristics of pillage politics. Poor as Haiti was, there was always some surplus to be appropriated. The property of the ruling elite was there for the taking by any coterie strong enough to seize the reins. So in 150 years, Haiti ran through some 30 heads of state, almost none of whom finished his term or got out at the end of it.

Many of them died to leave office, and their departures were followed by bloody, racist massacres--blacks revenging themselves on yellows, the yellows getting theirs back. In the long run, the blacks had the best of it, if only because there were more of them and they were the standard-bearers of unconditional negritude. The yellows were always suspected of being too French, in language, dress, and manners.

The only period of relative tranquility was the 20 years of American presence. From 1915 to 1934, a regiment of United States Marines helped keep order, improved communications, and provided the stability needed to make the political system work and to facilitate trade with the outside. Even a benevolent occupation creates resistance, though, not only among the beneficiaries, but also among the more enlightened members of the dominant society. Progressive Americans, including Paul Douglas (then a professor, later a senator from Illinois), reminded their compatriots that it was the United States, in the person of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, that had bestowed on Haiti its new constitution, which proudly affirmed that "the Republic of Haiti is one and indivisible, free, sovereign and independent." (FDR said "modestly: "… if I do say it, I think it is a pretty good constitution.") Douglas went on to warn his countrymen against the "slippery slopes" of imperialism. The United States should teach the techniques of administration and then leave the Haitians to govern themselves. To be sure, Haiti might not be ready for that, but if we couldn't do the job in 20 years, "there was little likelihood of our ever being able to do so."

No doubt. The United States left two years early, under the pressure of popular hostility and government opposition. The legislature then voted a new constitution (so much for Roosevelt's efforts), which enhanced Presidential authority without improving the assurance of tenure. Coup followed coup, until the election of François Duvalier in 1957. He was smarter than his predecessors: learning from experience, he emasculated the army and surrounded himself with a Pretorian guard of thugs. These were the tonton macoutes, country layabouts who liked nothing more than to beat, rob, and kill the educated elites of the cities, those literate few who might have nourished dreams of a better Haiti. Thanks to endemic terror variously applied (the fear is more potent than the fact). Papa Doc was able to die in office, in bed.

Not his son. He made the mistake of marrying a beautiful woman of cosmopolitan tastes and extravagant habits, a Marie Antoinette. Even her decorator had to stay at the Ritz. (Her mother-in-law, a real hard-liner, had never behaved that way.) Historians should rewrite their theories of revolution to take into account the spouse as well as the ruler.

It would be rash to predict happiness for Haiti. Nothing in history justifies anything but faith and hope. But there are some six million people there and counting--abysmally poor 80 percent illiterate, yet full of expectation--some 700 miles from our coast. We had better find something more potent and productive than charity.

David S. Landes is Coolidge Professor of History and Professor of Economics at Harvard. His latest book is Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World (Harvard University Press).

For more TNR, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.